Fact #1: The Monocacy Campaign was the last time a Confederate army invaded Maryland.

By the summer of 1864, the Confederacy was very much on the defensive. Union victories in 1863 ensured Union control of a vast amount of Southern territory. While the Confederates would launch other offensive operations in 1864 into Maryland, such as John A. McCausland's raid which burned Chambersburg, Gen. Jubal A. Early’s Confederate Army of the Valley District would be the last army-size force to cross the Potomac.

Fact #2: Braxton Bragg was the mastermind of the Monocacy Campaign.

In the summer of 1864, General Braxton Bragg, relieved of his command of the Army of Tennessee, served as Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ chief military advisor. It was in this capacity that he found out that Gen. John Breckinridge’s troops in the Shenandoah Valley were under severe pressure from Union Gen. David Hunter’s Union troops. Bragg passed this news to Davis, adding that “it seems to me very important that this force [Hunter’s] of the enemy should be expelled from the Valley. If it could be crushed, Washington would be open to the few we might then employ.” Davis informed Gen. Robert E. Lee of the idea and three days later Early’s troops set out for the Shenandoah Valley, and then the North.

Fact #3: Early’s invasion was meant to be a diversion from the fighting near Richmond.

Lee ordered Early’s Corps north only days after the bloody Battle of Cold Harbor, east of Richmond. While no copy of his orders to Early exists, Early stated after the war that he was directed “to strike Hunter’s force in the rear, and, if possible, destroy it; then move down the Valley, cross the Potomac near Leesburg in Loudoun County, or at or above Harper’s Ferry, as I might find most practicable, and threaten Washington City.” This would force Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, directing Union operations against Richmond, to divert precious troops to the defense of Washington because…

Fact #4: When Early invaded Maryland, Washington was practically undefended.

The heavy casualties sustained during the Overland Campaign forced Grant ordered almost all of the troops manning Washington’s defenses to join his army in Virginia. Confederates confidently anticipated that if they could invade Maryland Grant would have to send troops north to defend the capital.

Fact #5: John W. Garrett, President of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, played a key role in assisting the Union troops at Monocacy.

After Early drove David Hunter’s army away from Lynchburg and into West Virginia, the Union lost track of his army. The first indication any Union commander got of Early’s march toward the Potomac was from John W. Garrett, the president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Garrett—always wary of threats to his railroad—met with General Lew Wallace and warned him that his workers had spotted Confederate cavalry patrols near the railroad west of Harpers Ferry. If not for Garrett’s warning and the information he continued to pass on to Wallace, the Union might never have discovered Early’s invasion in time to react. The B&O Railroad also played a key role in helping Union troops to reach Monocacy Junction in time for the battle.

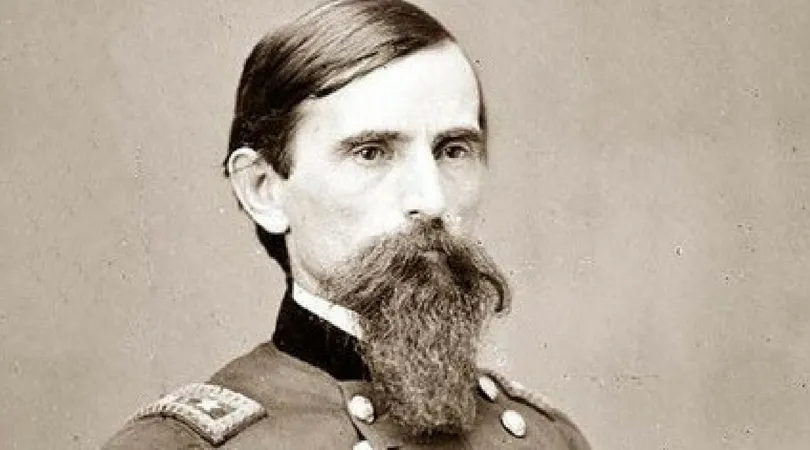

Fact #6: Lew Wallace, later the Author of "Ben Hur," Commanded Union Forces at the Battle of Monocacy

In 1864 Lew Wallace commanded the Middle Department, a sleepy command responsible for defending the parts of Maryland east of the Monocacy River. Wallace’s entire department could only muster a little over 3,000 men, of which only 2,500 could be spared to react to Early’s invasion. Wallace set out for Monocacy Junction as soon as he ordered what troops he could spare to gather there, riding in the engine cab of a steam locomotive Garrett made ready for him in Baltimore. Years after the events of 1864, Lew Wallace wrote the novel "Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ" which went on to become the second most-printed book of the 1800s, only beaten by the Bible itself.

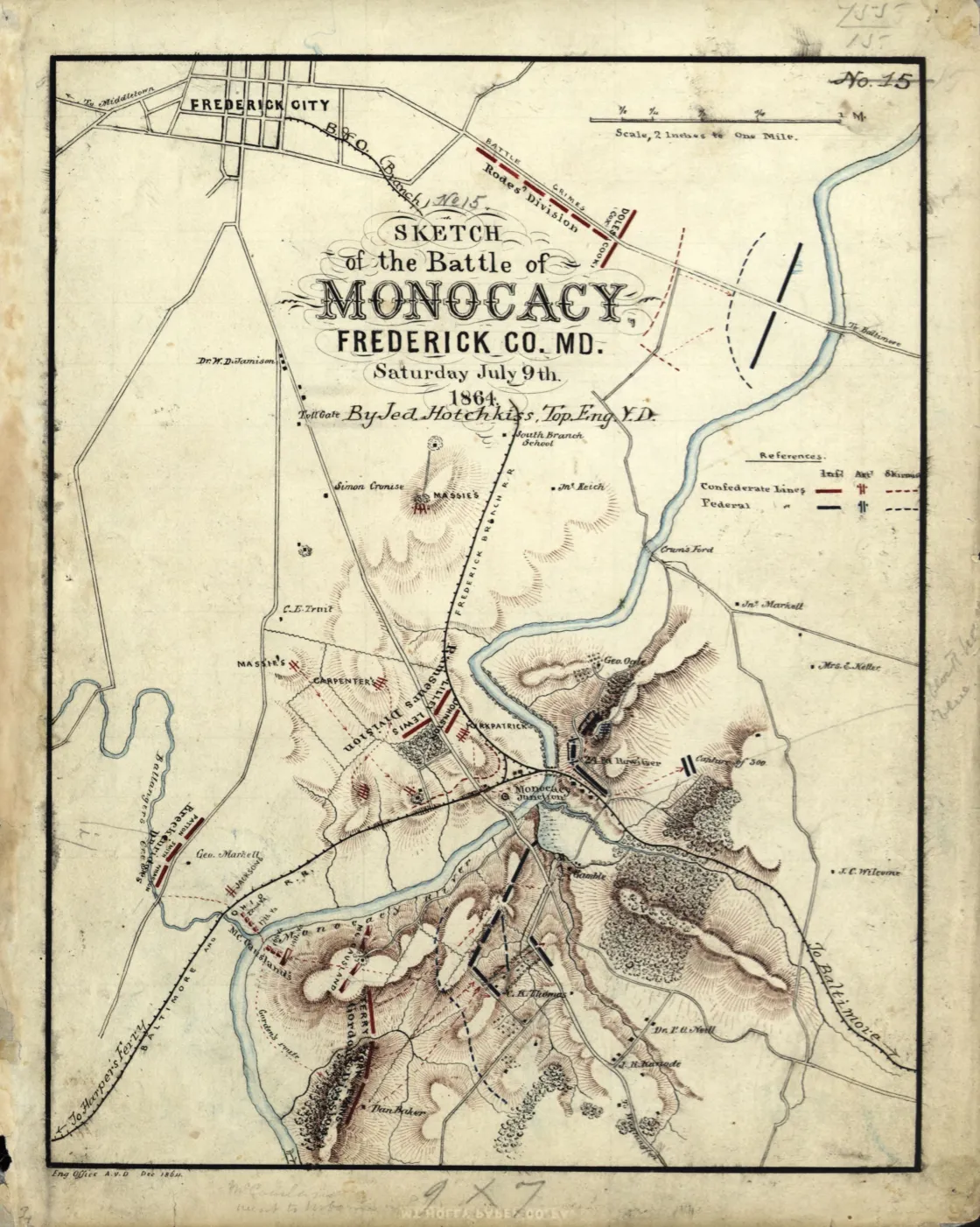

Fact #7: Monocacy Junction was the best spot to delay Early’s advance on Washington, D.C.

Monocacy Junction was a natural chokepoint for Early’s army. The Monocacy River has steep banks, leaving few options to ford the river, and only two road bridges across it, one leading to Washington and the other to Baltimore. This meant Wallace could cover the approaches to both cities at once. On the east bank tall hills dominate the landscape, good for artillery. Wallace saw all this when he surveyed the ground two days before the battle and knew that Monocacy was the best place to fight a delaying action against Early’s army.

Fact #8: Only one day before the battle, Lew Wallace was reinforced by James Ricketts’ Division from Petersburg.

As soon as he received word of Early’s invasion of Maryland, Grant dispatched Gen. Horatio Wright’s Sixth Corps north from Petersburg to reinforce Washington. The first of his three divisions, commanded by Gen. James Ricketts, who commanded an artillery battery at Bull Run three years earlier, landed in Baltimore on July 7. His 3,500 veteran troops arrived at Monocacy Junction the next morning, less than 24 hours before Early’s men would appear east of Frederick.

Fact #9: Only a small part of each army participated in the fighting during the Battle of Monocacy.

When the Confederate troops arrived opposite Monocacy Junction on July 9, Jubal Early decided that instead of attacking the Union head-on, he would flank the Union troops. While Gen. Stephen Ramseur’s division skirmished with the small Union force on the west bank of the river defending the junction, he sent Gen. John B. Gordon’s Division, the remnants of the famous “Stonewall Division”, along with Gen. John McCausland's cavalry brigade south to ford the river and find the Union flank. Wallace spotted them and ordered Rickett’s division to stop them. The resulting fight at the Thomas Farm on the Union left saw around 5,000 Confederates fight Rickett’s 3,500 Federals. That is slightly more than half of Wallace’s 6,000 men and only a third of Early’s 15,000 strong army. The remainder of both either skirmished or were held in reserve. However, despite the small numbers engaged, the fighting between the veteran troops at the Thomas Farm was described by the combatants as the fiercest of the war, with each side sustaining around 1,000 casualties in just 3 hours.

Fact # 10: The Battle of Monocacy saved Washington D.C.

Lew Wallace’s delaying tactics at the Battle of Monocacy and the fierce fighting at the Thomas Farm forced Early’s army to halt and rest the next day on the battlefield. When he reached the outskirts of Washington two days later, the other two divisions of Horatio Wright’s Sixth Corps had just arrived and were manning the city’s defenses. After two days of intermittent fighting at the Battle of Fort Stevens, Early decided to withdraw back into Virginia. The threat to the capital was over, and the Confederates would never again place an army on Northern soil east of the Mississippi River. If not for the crucial two-day delay caused by the Battle of Monocacy, Early would have captured Washington before it could be reinforced with untold consequences for Abraham Lincoln on the eve of the 1864 presidential election.