Monocacy National Battlefield, Frederick, Md.

Located approximately 13 miles north of the Potomac River, Frederick, Maryland, witnessed the campaigns, battle and aftermath of the American Civil War. Armies passed through the community in 1862 and 1863, and the nearby Battle of Monocacy in 1864 helped to protect the national capital.

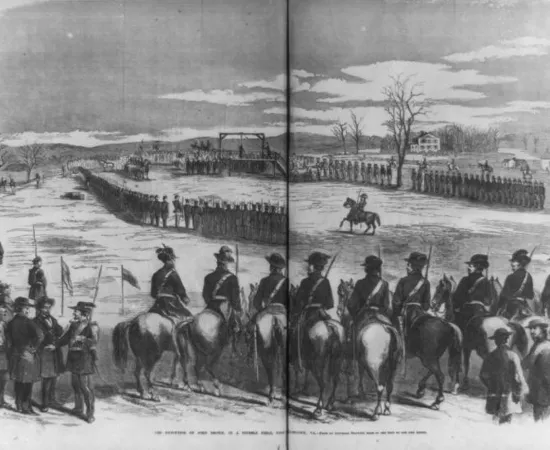

In October, 1859, the citizens of Frederick County, Maryland, were shocked by the slave revolt which John Brown and his followers attempted to provoke just across the Potomac River in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The raid sparked another heated national debate over slavery, just before an election year. Even still, nobody in Frederick could have imagined exactly what their local news would spark just over a year later.

The 1860 election found the Democratic Party with a three candidate split ticket and Abraham Lincoln running for the Republican Party. In Frederick, however, it was a tense battle between two Demcratic Party candidates: John Bell and John C. Breckinridge. Bell represented the moderate Constitutional Union Party. Bell and his running mate, Edward Everett, espoused a platform focused instead on preserving the Union instead of addressing slavery. Breckinridge, meanwhile, was a Southern Democrat, and his platform had pro-slavery and pro-secession views. Frederick’s voting patterns were typical of Maryland as a whole. Of the 7,331 votes cast in Frederick County, Breckinridge received 3,167 and Bell 3,616, giving him the narrow victory. Abraham Lincoln, by contrast, gathered a measly 103 votes in the county. Frederick appeared pro-Union, but only just, and it did not favor of Lincoln’s views.

As southern states seceded to form the Confederacy, Maryland become a border state on the frontlines of the Civil War. Frederick did not see the political violence like Baltimore. Instead, it watched anxiously as Harpers Ferry traded hands multiple times in 1861. The first Confederate “invasion” of the north saw Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s garrison troops occupy the Maryland Heights, almost in sight of Frederick. The those troops were quickly ordered back to the Virginia side of the river, the threat of occupation was ever-present to the citizens of Frederick.

That fear became reality in September 1862, when Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia invaded Maryland. Lee’s troops crossed the Potomac south of Frederick and marched up the Monocacy River, occupying the city. “Stonewall” Jackson attended a Sunday church service in town, where one of his staff saw him sleep through the sermon. Lee, in his headquarters tent just outside of town, drafted Special Order 191, the famous “Lost Order.” The Confederate occupation brought to the surface tensions within the town over secession, with pro-southern townsmen openly aiding the Confederates. A Frederick resident warned Confederate generals that General George B. McClellan discovered a lost copy of Special Order 191.

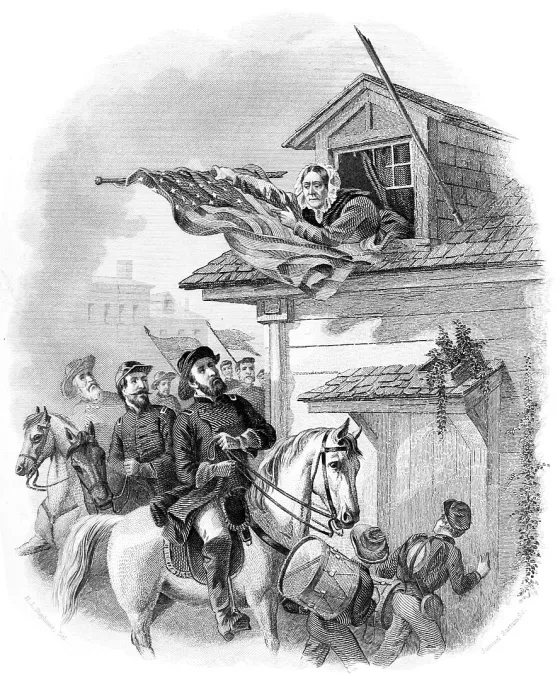

Meanwhile, the moderates loathed the occupiers. Perhaps more than any political stance, Confederate occupation convinced many of Frederick’s residents to side with the Union. The story of Barbara Fritchie, made famous by John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem, exemplified Frederick’s newfound animosity toward the Confederates. Even as thousands of armed Rebel troops marched by her home, the elderly Fritchie waved an American flag out of her window in open defiance. Allegedly, when Confederate troops tried to compel her to remove the flag, “Stonewall” Jackson himself intervened on her behalf. Though its authenticity is uncertain, Fritchie’s story was nationally recognized as a symbol of Frederick’s resistance to Confederate occupation. When McClellan’s Army of the Potomac passed through, chasing the Confederates, they were given a hero’s welcome.

However, the Union Army took its toll upon the town, too. As the armies passed through, soldiers trampled crops for camps, tore down fences and buildings for firewood, and stole all varieties of property from food to silverware to farm tools. Local residents filed claims for the damages with the Federal government, and many were given payments, but the payments often did not cover the full cost of the losses. Others were denied payments, either because they did not supply proper proof or because they were known to be southern sympathizers.

Lee, in his escape, burned the bridges over the Monocacy River, which were expensive to repair. One of those bridges belonged to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which lobbied Washington to post a garrison nearby to protect it from another attack. Shortly after the Battle of Antietam, the 14th New Jersey Infantry arrived and constructed Camp Hooker, overlooking the bridge and nearby Monocacy Junction. The troops, their officers, and especially Major Vredenburg’s dog “Dash”, befriended the local farmers during their stay. In their two-year tenure, the most exciting enemy action they encountered were brief appearances by John Singleton Mosby’s raiders, who tried to damage the B&O railroad on multiple occasions.

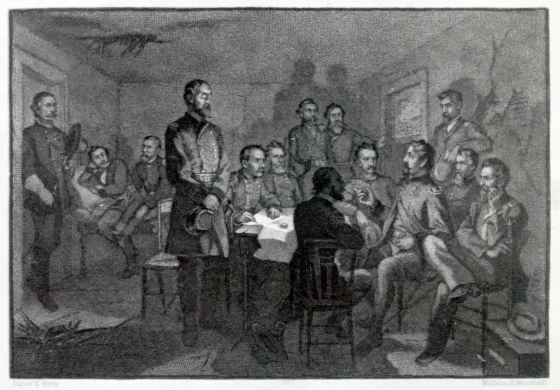

The 14th New Jersey remained near Frederick even as the Army of the Potomac marched by on their way toward Gettysburg. General Winfield Scott Hancock annoyed his II Corps troops by insisting they not take off their shoes, socks, and pants as they waded across the Monocacy in late June 1863. His wet soldiers resented the decision. Hancock, for his part, refused to let the disrobing slow his column down. The same day, inside Prospect Hall on the outskirts of Frederick, George Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac from Joseph Hooker.

The next spring Grant ordered the 14th New Jersey to join his army in Virginia. Frederick was once again undefended. This would not have been an issue except for Confederate General Jubal Early’s invasion of Maryland in July 1864. Early’s troops crossed the Potomac at Shepherdstown, bypassed the Union garrison garrison atop Maryland Heights and headed for Frederick. General Lew Wallace, commanding the Middle Department, hastily assembled a blocking force on the Monocacy River near Monocacy Junction. To buy time for more troops to arrive, Wallace ordered David Clendenin’s 8th Illinois Cavalry to slow Early down. The cavalry, later joined by some infantry under General Erastus B. Tyler, fought a running battle with Early’s cavalry all day on July 7. They successfully kept the Confederates out of Frederick, the fighting reaching the western outskirts of town, but the next day they were forced to abandon the town for the safety of the Monocacy River.

Early entered Frederick, along with the bulk of his army, on July 9, 1864. He ordered General John C. Breckinridge (who won Frederick’s vote four years in the 1860 presidential election) to dislodge Wallace’s troops from their defenses, while Early himself remained in Frederick that morning. He met with the town’s leaders and presented them an ultimatum. If they did not provide him $200,000, he would burn Frederick to the ground. Five local banks hurriedly gathered up the money in wicker baskets and provided it to the town as a very low interest loan. Early was not present to receive the ransom that afternoon, as he departed to managed the rapidly intensifying fight at Monocacy Junction. The ransom paid, Frederick was spared the torch, if significantly poorer for it. The $200,000 ransom equates to more than $4 million today. This was in addition to all the incidental damages brought about by Confederate occupation, like those of 1862.

Not long after the ransom was paid, General John B. Gordon’s Division’s charge defeated the Federals and ended the Battle of Monocacy. The battle devastated the properties where the troops fought. A doctor who visited the Thomas Farm, the site of Gordon’s charge, a week later observed the damage. He wrote in his diary that “There was abundant evidence at Keefer Thomas’ house of a terrible fight, -- shells had passed into it at many points, and musket balls had perforated the windows and porch in various directions. In the field were buried a number of confederate soldiers, mostly from Georgia & Louisiana.”

Like in 1862, many residents made claims with the Federal government to repay damages, but this time nearly all were denied. The government in 1863 made the decision to only reimburse damages caused by Union troops. Battle damage or Confederate destruction no longer qualified. As a result many of the farmers lost their 1864 harvests and had to cover the costs with their own money, if they even had money to spare. The Federal government also refused to cover the costs of the ransom. The City of Frederick therefore levied a ransom tax in order to pay off the bank loan. The tax income did not fully pay off the debt until 1951.

After the Battle of Fort Stevens and Early’s withdrawal into the Shenandoah Valley, Grant, Sheridan, and Hunter met at Monocacy Junction to plan the campaign that finally drove the rebels out of the valley. Sheridan’s army passed by Frederick en-route, the last major army to do so during the war. The city, in particular Monocacy Junction, continued to play a critical role as a supply and hospital hub during Sheridan’s valley campaign. Its role in the fighting, however, was at an end.

Today Frederick retains many of its historic structures, including Prospect Hall and a reconstructed version of Barbara Fritchie’s house. It is also home to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Just outside of town lies the Monocacy Battlefield, where you can still see Kiefer Thomas’ House, which the American Battlefield Trust, thanks to generous donor support, saved in 2002. Frederick, a crossroads of the Civil War, surrounded by battlefields and historic sites, remains one of the best places to explore America’s wartime history.

Related Battles

12,401

10,316

23,049

28,063

2,325

2,685

12,636

286