The city of Baltimore, Maryland, was significantly impacted by the Civil War and, in turn, played a shaping role in the development of the war. Learn more about Baltimore during the Civil War through these ten facts.

Fact #1: In the months leading up to and immediately following the outbreak of the Civil War, divided loyalties created a city rife with tension.

Maryland was a slave state and never officially seceded like many of its Southern sisters. However, in the first months of the war, it was unsure to which side Maryland would tip. Baltimore was exemplar of these tensions. The city itself had the feel of a northern city with its focus on industry and manufacturing, but many of the social and political elites of the city favored the Confederacy and owned slaves. The large immigrant population, in combination with the largest free African American community in the country, favored Union and abolition. A confrontation between these groups was imminent.

Fact #2: By the 1860s, Baltimore had the largest free African American population in the country.

Free Blacks organized more than 20 churches, 30 benevolent societies and charities, and many schools. They were also instrumental in the conduct of the Underground Railroad, Baltimore being an important stop for former enslaved people escaping from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Frederick Douglass spent his early years in Baltimore learning how to read and write before travelling further north.

Fact #3: Because Baltimore was a transportation hub, it was essential to the Union war effort and was the North's gateway to the South.

Baltimore was the terminus of three different railroads: the Baltimore and Ohio, the first long-distance and passenger railway in the country, the Northern Central, and the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore. The secession vote of Virginia on April 17, 1861, further emphasized Maryland’s importance; through her was the only way troops could reach Washington, DC. As the war wore on, Baltimore’s railroads would be essential to the movement of Union troops.

Fact #4: Baltimore was the site of the first blood spilled during the Civil War.

Even before massed Union and Confederate armies met on the field of battle, the first casualties of the war occurred in Baltimore. On April 19, 1861, only a week after the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the 6th Massachusetts Infantry was passing through Baltimore en route to Washington, DC, to defend the capital from Southern armies forming across the Potomac River in northern Virginia. A large contingent of pro-Southern Baltimore citizens, angry that federal troops passing through their city would be used to suppress their sister state, began harassing the troops, first verbally, and then by throwing rocks and bottles. Soon, gunshots rang out and a riot ensued. Four soldiers were killed and thirty-six were wounded, with more than a dozen civilians killed. The Pratt Street Riot, as it came to be called, further incensed Northeners.

Fact #5: The Pratt Street Riot inspired the song "Maryland, My Maryland."

One of the men killed in the riot was a one Francis X. Ward, who was friends with native Baltimorean James Ryder Randall. In response, Randall composed the poem “Maryland, My Maryland,” which begs the listener to “avenge the patriotic gore that flecked the streets of Baltimore.” The poem’s intensely pro-Southern words were set to the melody of “O Tannenbaum” by fellow Baltimorean Jennie Cary. Sometimes called “The Marseillaise of the South,” it became a Confederate marching song and was banned by Union authorities in Maryland. During the 1862 Antietam Campaign, Confederate General Robert E. Lee reportedly ordered his soldiers to sing the song as they marched through the town of Frederick, hoping to garner support from locals.

Fact #6: Federal troops were present in the city after the riots to keep Confederate sympathizers at bay.

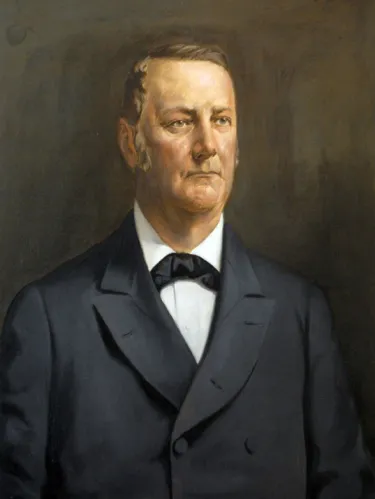

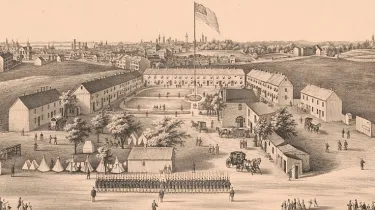

After the riot had ended, Baltimore mayor George W. Brown and Maryland Governor Thomas H. Hicks determined that no more federal troops should pass through the city, siding with the rioters. They begged President Abraham Lincoln to bring troops to Washington via an alternative route, but as Lincoln drily noted, his soldiers could not fly or burrow under the state; Maryland was the only way. In response, Brown and Hicks ordered Maryland militia to burn railroad bridges north of the city to forcibly prevent troops from coming into the city. Brown describes the city as a state of “armed neutrality.” Tensions nearly escalated between pro-Southern city officials and the Union garrison at Fort McHenry, and Maryland seemed to be on the verge of secession. Then, on May 13, almost a month after the riots, Union General Benjamin F. Butler and a contingent of federal soldiers occupied Federal Hill, the heights above downtown Baltimore. This show of force quelled pro-Confederate action within the city and federal authority was restored; Maryland would not secede.

Fact #7: After President Lincoln's suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, civilians suspected of being Southern sympathizers, as well as prisoners of war, were held in Fort McHenry.

By the end of the war, more than 2,000 civilians had been arrested and imprisoned in Fort McHenry, including the grandson of Francis Scott Key. These charges varied in severity and veracity, but most of the citizens held in Fort McHenry were held indefinitely, made possible by Lincoln’s wartime suspension of the writ of habeas corpus (literally “show me the body”). One Maryland lawmaker was arrested for singing “Dixie.” The most famous of those imprisoned was John Merryman, whose arrest prompted a legal showdown between President Lincoln and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney over the limits of presidential power. Taney ruled that only Congress, not the President, could suspend the writ, but Lincoln ignored his ruling, citing the crisis at hand. Ex Parte Merryman, as the case was called, set important legal precedents in the American tradition, extending all the way into the 21st century. Additionally, Confederate prisoners of war were temporarily held there before being transferred to other prisons.

Fact #8: Baltimore was a vital base for the Union Navy's activities in the Chesapeake Bay.

After the Union naval base at Norfolk, Virginia, was captured by the South in 1861, Baltimore became a vital base for naval activities in the Chesapeake Bay. The city’s vibrant shipyards rebuilt damaged vessels, and the city’s mills produced steam engines and armor plating for ships such as the USS Monitor.

Fact #9: In the aftermath of the Battles of Antietam and Gettysburg, the city of Baltimore transformed into an immense hospital complex.

After the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, Union and Confederate casualties from the single bloodiest day in American history arrived in Baltimore via the B&O Railroad from Frederick. City officials transformed churches, hotels, warehouses, parks, and every other open space into hospitals. A similar phenomenon occurred after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. Many of the Confederate officers who were wounded in Pickett’s Charge were treated at Fort McHenry’s hospital.

Fact #10: President Lincoln visited Baltimore three times.

President-elect Lincoln passed through Baltimore under the cover of darkness on February 23, 1861, en route to his inauguration. Detective Allan Pinkerton, hired to provide security on the journey, was convinced of a plot to assassinate the president-elect in Baltimore, a city already known for its Southern sympathies. More than three years later Lincoln returned on April 18, 1864, to speak at the Maryland State Fair for Soldier Relief. He found a much-transformed city from the city he had to virtually sneak through in the fraught early months of 1861. Finally, on April 21, 1865, Lincoln’s funeral train passed through the city on its way to Springfield, Illinois.