U.S. Army Medal of Honor

On December 13, 1862, in the field near Fredericksburg, Virginia, that would come to be known as “Slaughter Pen Farm,” a veritable hell on Earth erupted and unfolded. It’s in the midst of such horrific battle that men sometimes find a courage that compels them to unthinkable acts of honor, and that was the case here. Five soldiers were later bestowed the Medal of Honor for their actions on this field on that bloody day: George Maynard of the 13th Massachusetts, Charles Collis of the 114th Pennsylvania, Philip Petty of the 136th Pennsylvania and Martin Schubert and Joseph Keene of the 26th New York Infantry.

Born in Waltham, Massachusetts, in 1836, George Maynard worked as a watchmaker before enlisting in the 13th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in July of 1861. His regiment participated in many of the war’s early battles, including the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Battle of Ox Hill and Antietam. On December 13, 1862, the regiment’s Col. Samuel Leonard ordered four companies to support Capt. James Hall’s Second Maine Battery on Gen. George Meade’s right flank, with the rest of the companies, including Maynard’s, to fall back to Bowling Green Road. When Maynard reached the road and realized his comrade Charles Armstrong was missing, he went back into the fray to find him. Armstrong was badly wounded in the thigh. Maynard tied a tourniquet around Armstrong’s leg and carried him back to the Union lines. In 1898, Maynard would receive the Medal of Honor for this selfless act, with the citation reading: “A wounded and helpless comrade, having been left on the skirmish line, this soldier voluntarily returned to the front under a severe fire and carried the wounded man to a place of safety.” Armstrong would not survive, however, and died later that night at a field hospital.

In March 1863, Maynard mustered out for promotion to first lieutenant in the Fifth U.S. Volunteers, later the 82nd United States Colored Troops, of which he later became a captain. Late in his service, he contracted malaria and suffered from scurvy, both of which impacted the rest of his life. He mustered out in September of 1866 and returned to being a watchmaker. Maynard was granted a pension for his ailments, including the loss of most of his teeth.

On May 5, 1868, Maynard married Harriet Elizabeth Henry of Boston. They had seven children together, four of whom died in childhood and three of whom died in their early 20s. Maynard became a member of the military organization the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts in 1875. He died in 1927, at the age of 91, having outlived his wife and all his children. He’s buried in the Mount Feake Cemetery in Waltham.

“A Critical Moment”

On February 4, 1838, Charles Henry Tucker Collis was born in Cork, Ireland, the first son of William and Mary Collis. The family eventually moved to England, where Mary bore five more children. In the spring of 1853, 15-year-old Collis and his father set sail for Philadelphia. On March 1, 1854, Mary and the other five children set sail to join them, but the ship never made it. His mother, two brothers, and three sisters were lost at sea. It’s believed the ship sank after hitting an iceberg. Collis and his father were forced to find a new life without them.

Fortunately for Collis, he landed under the tutelage of influential local attorney and politician John Meredith Read. By 1859, he was admitted to the bar. Shortly before the war broke out, he married Septima Levy. Eager to defend the Union, he enlisted with the 18th Pennsylvania upon Abraham Lincoln’s Call for Volunteers in April 1861. The 18th Pennsylvania spent much of its three-month term of enlistment stationed at Fort McHenry in Baltimore. They returned home and he mustered out on August 7, 1861. Immediately, Collis set out to raise a company of Zouaves d’Afriques and was soon granted approval. The Zouave craze had swept the nation, and Collis outfitted his men with the French-influenced uniform: baggy red pantaloons, a short blue Zouave jacket with a lighter blue cuff, white leggings and a light blue merino sash around the waist, topped by a red fez and white turban.

In January 1862, with the help of now Judge Read, Collis was authorized to raise a battalion that would soon move south. In late May, Collis’s men joined Capt. Robert Hampton’s First Pennsylvania Artillery, a small force of cavalry and additional infantry in a skirmish with Gen. Thomas Jackson’s men in Middletown, Virginia. Their presence successfully rerouted Jackson toward Strasburg, instead of Winchester. On September 1, 1862, Collis was promoted to colonel and instructed to recruit a regiment, which became the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry.

As the fighting raged on December 13, 1862, Collis’s Zouaves, many untested by battle, crossed the lower pontoon bridge on the Rappahannock in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and made their way to the field now known as Slaughter Pen Farm. Gen. John C. Robinson rode in front of the 114th Pennsylvania to guide them into their first battle. As he did, a solid shot ripped through his horse, sending Robinson to the ground. The explosion of another artillery shell killed his bugler, and Pvt. Samuel Hamilton “had his head shot off,” one of the Zouaves later recounted. Stunned and horrified, the Zouaves recoiled. Colonel Collis raced to the front, grabbed the regimental flag and rode to the center of the line to rouse his men, shouting, “Remember the stone wall at Middletown!” The 114th rallied and swept into the fire. “Nothing was to be seen but smoke and dirt flying from cannon balls,” a Zouave later wrote. “I have heard of hot places; I now know what they are.”

On March 10, 1893, Collis received the Medal of Honor; the citation reading: “Gallantly led his regiment in battle at a critical moment.”

In May 1863, Collis was wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville and contracted typhoid. In August 1863, he became a brigade commander under Maj. Gen. David B. Birney. On December 12, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln nominated Collis for appointment to the brevet grade of brigadier general of volunteers to rank from October 28, 1864, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on February 14, 1865. Collis was mustered out of the army on May 29, 1865. On January 13, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Collis for appointment to the brevet grade of major general of volunteers to rank from March 13, 1865, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on March 12, 1866.

After the war, Collis returned to law. He died on May 11, 1902, and is buried at Gettysburg National Cemetery.

Rally on the Flag

In battle, the act of bearing the colors was itself a sacrificial bravery. Consuming both hands to grasp it, the bearer could not at the same time bear arms to defend himself. This was a precarious situation, since the flags were of utmost importance, guiding troops and acting as rallying points. Hence, color bearers were a prime target for enemy shooters. A source of supreme pride, as well, it was a great dishonor to lose one to the enemy in action. Many flags were threatened during the fiery storm of battle at Slaughter Pen Farm, and Philip Petty, Martin Schubert and Joseph Keene each received their Medal of Honor for defending the colors.

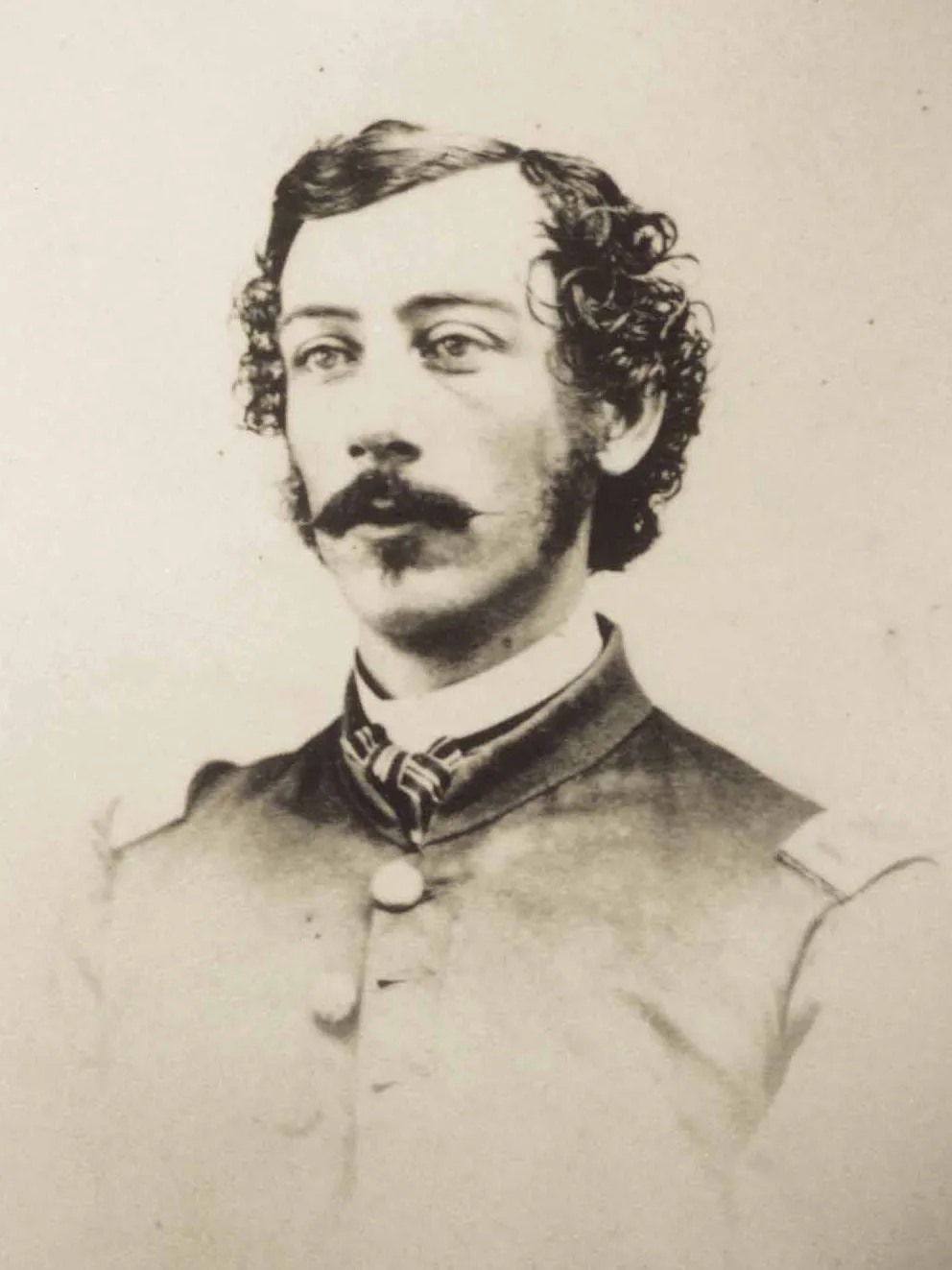

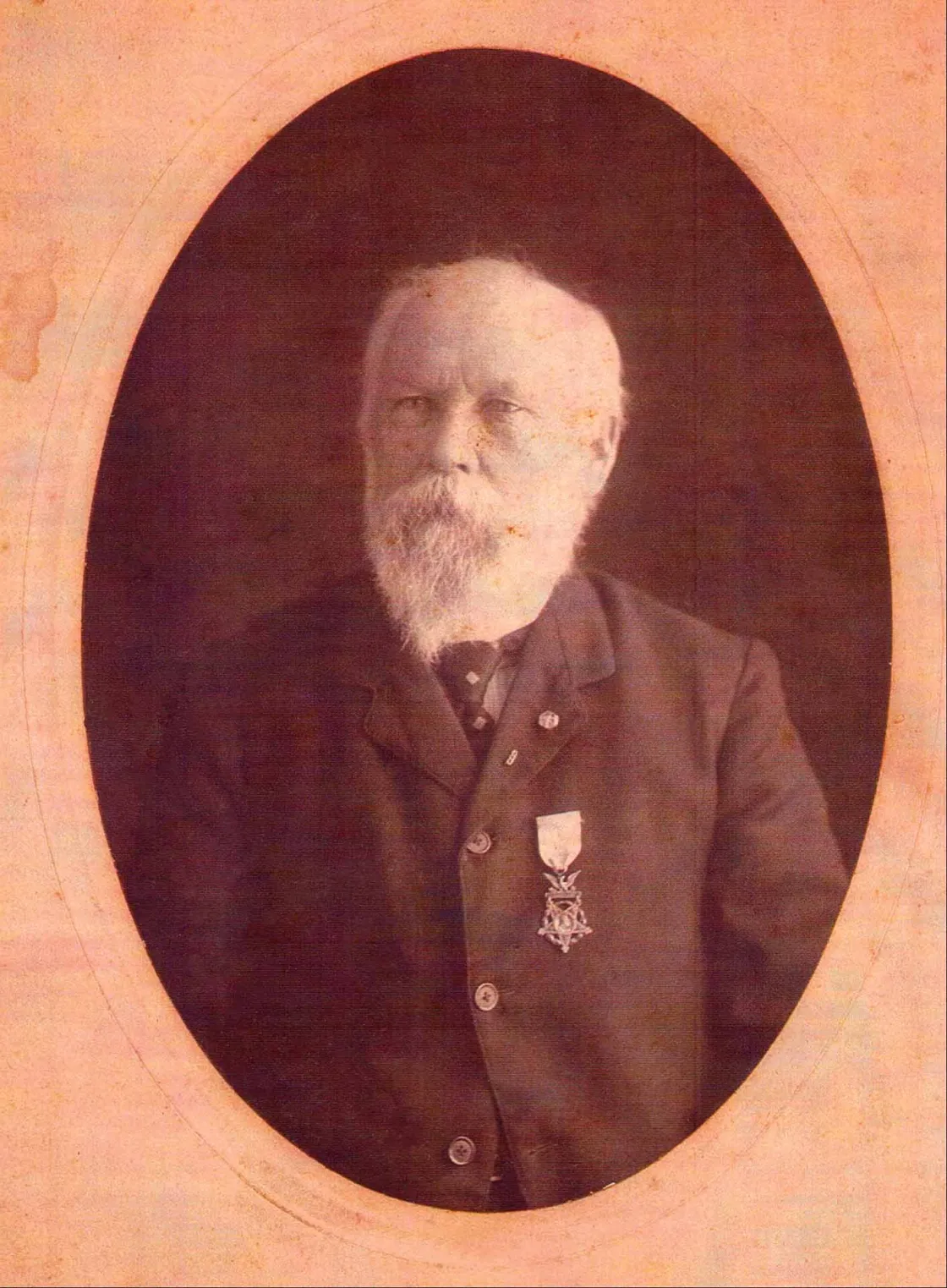

When the color bearer of the 26th New York Infantry was wounded as the unit advanced across the Slaughter Pen, and the flag fell to the Earth, German immigrant Martin Schubert sprang forward to defend it. Most remarkably, Schubert was not even supposed to be there. Wounded at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, he had been granted a medical furlough. “I went into battle with the regiment, however, against the protests of my colonel and captain, who insisted that I should use the furlough. I thought the Government needed me on the battlefield rather than at home,” Schubert later wrote.

Schubert carried the flag until he was shot on the left side, a bullet he carried for the rest of his life. His Medal of Honor citation reads: “Private Schubert relinquished a furlough granted for wounds, entered the battle, where he picked up the colors after several bearers had been killed or wounded, and carried them until himself again wounded.”

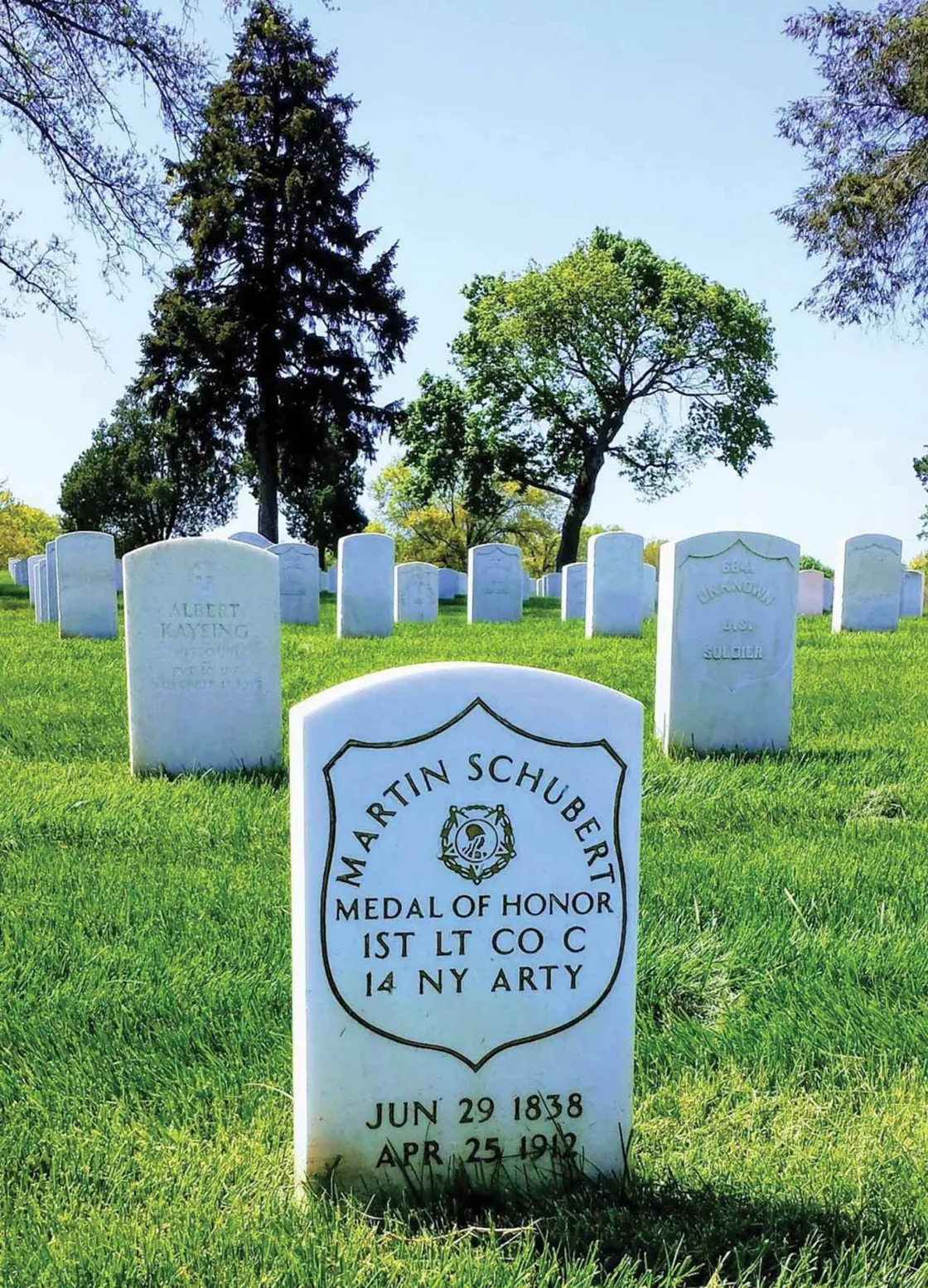

On December 22, 1862, Schubert was promoted to corporal. He mustered out of this unit in May 1863 in Utica and subsequently served with the 14th New York Heavy Artillery, where he eventually rose to the rank of first lieutenant.

After the war, Schubert returned to his work as a butcher. In 1893, he joined the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), an organization of military officers dedicated to preserving the United States government after Lincoln’s assassination, and became its treasurer. He died on April 25, 1912, in St. Louis, Missouri, and is buried in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in Lemay, Missouri.

When Schubert fell wounded with the flag, another immigrant in the 26th New York picked up the colors and the advance. A former Englishman, Joseph Keene saw the flag of the 26th New York laying on the ground, hoisted it up and advanced with the regiment. He bore the colors throughout the fight and got them safely off the field. In 1892, he was bestowed the Medal of Honor, the citation reading: “[V]oluntarily seized the colors after several Color Bearers had been shot down and led the regiment in the charge.”

Keene mustered out with this regiment in May 1863 and re-enlisted with the Third New York Heavy Artillery in June 1863. He mustered out of the U.S. Army in July 1865. He died in 1921 and is buried in buried in Whitesboro, New York.

Just down the line from the 26th New York was the 136th Pennsylvania Infantry, a fresh nine-month-old regiment from western Pennsylvania. The unit’s color bearer, 250-pound S. Dean Canan, made a perfect target for the Rebels, with some singling him out for aim. Unnerved and terrified under fire, the untested Canan dropped the colors and ran away. When Pvt. Philip Petty saw the discarded banner, he grabbed it up and moved forward, rallying his men to move across the field with him. Moving ahead of the line at one point, he planted the flag in the ground, knelt beside it and began to fire at oncoming Confederates. The 136th cheered him on.

Petty, of Jackson Summit, Pennsylvania, had enlisted August 1, 1861, at Harrisburg in Company C of the 12th Pennsylvania Reserve Corps, or Troy Guard. He served with them until March 1862, when he was discharged for physical disability due to typhoid. He re-enlisted in August of 1862, in Company A, of the 136th Pennsylvania.

Remarkably, Petty’s records list his rank as a musician — proving, as all these men’s stories do, that in the thick of battle, men are driven to courage above any rank or prior profession. It’s a higher calling of duty and honor.

Related Battles

12,500

6,000