Saving Old Dirt: The Preservation of Earthworks

Earthworks at Fort Necessity National Battlefield, Farmington, Pa.

Soldiers have long used physical barriers to protect themselves using whatever was available—existing stone walls, fences and terrain—as cover. They could also augment these features or construct fortifications from scratch.

A few examples: During the Revolutionary War, the American and French armies at Yorktown constructed a series of parallel earthworks to shield their movements as they moved ever-closer to the British defenses, ultimately bombarding them into surrender in a victory that cemented American independence. The dramatic topography around Vicksburg, was enhanced with earthen redoubts by the besieged Confederate army, creating daunting defenses. The towering bulwark of Fort Fisher protected the South’s precious harbors. The long, snaking lines that marked the beginnings of trench warfare are still visible in the woods around Petersburg.

These remain valuable teaching tools for those seeking to understand the battlefields’ landscape, but their very nature makes them vulnerable. Modern historians and preservationists are faced with a deceptively simple question: How do you protect dirt from erosion and allow future generations to learn on battlefields?

How Earthworks were Preserved in the Past

Long before any modern cultural resource protection guidelines existed, one way to extend the lifetime of earthworks was to simply redig them, as famously happened at the Yorktown Battlefield. After the 1781 siege, General George Washington ordered that his siege lines be destroyed so British forces could not use them to retake the town and surrounding area. In 1862, Confederates reworked much of the British defenses surrounding the town, thus altering the interpretive landscape dramatically. Then, in the 1930s, at the height of the Great Depression, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employees began to redig the American and French trenches surrounding the Yorktown Battlefield.

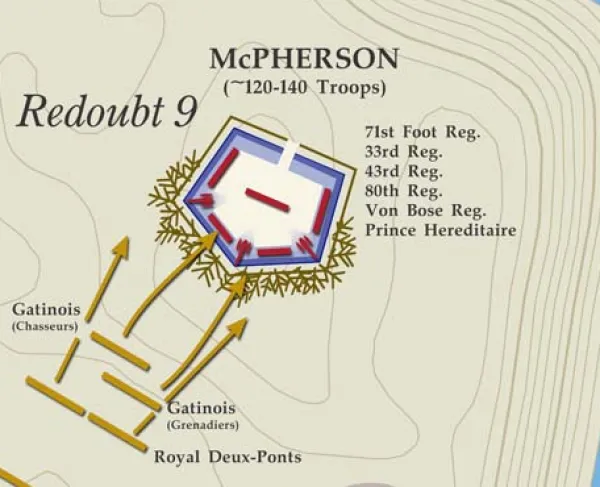

With the oversight of archaeologists, workers followed engineer maps and archaeological data to reconstruct the Allied lines the same way they had been dug in 1781, by hand. To replicate the multiple layers of defenses that comprise an earthen fortification, the CCC workers installed stone fraises in the walls of redoubts 9 & 10.

In 1781, the fraises were wooden and meant to keep out attacking infantry, but in 1930, the park thought the stone recreations could keep the earthworks in place and fight erosion. The result can be seen today; visitors may think the earthworks at the battlefield are original, but most come from the CCC’s work. Such examples can be found on the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania battlefields and the Continental Army encampment at Valley Forge.

Sometimes the Best Thing To Do is Nothing

Many earthworks today can be found snaking through woods from Petersburg to the Wilderness; earthworks in wooded areas are best preserved when left alone. The National Park Service’s study into the matter concluded that:

Earthworks under forest cover are the most well-stabilized. The naturally acid condition of the soils inhibits some decomposition and actually reduces the rate at which organic matter, such as heavy timbers and old root systems, deteriorates. This is counteracted when the soils are limed to support turf grasses and other non-native vegetation. The forest structure, which is visibly layered above ground, with canopy, understory, shrub, and ground layers, is also layered below ground, with a complex of layered roots which in mass are equal to the trunks and branches above. This does not mean, however, that they are without problems. Erosion and trampling may be locally severe, especially when these areas are adjacent to interpreted sites or other facilities. Damage from animal burrowing and dead or windthrown trees also occurs.

By keeping visitors off the earthworks by virtue of remoteness or dense foliage cover, one of the main eroding factors in earthwork preservation is addressed. The dense root systems keep dirt in place, and many such earthworks appear as though they haven’t changed since they were abandoned.

Continuing Threats

Erosion is an ever-constant challenge, and Vicksburg National Military Park is fighting an uphill battle. The loess soil that makes up the bluffs and surrounding countryside of Vicksburg, Mississippi, is particularly vulnerable to erosion; many of the battlefield’s most familiar locations have been forever altered by nature’s slow advance.

Visitor safety has also become a concern. After significant storms, Vicksburg closing to the public is not an uncommon occurrence; large field fortifications are undercut by water flow, roads are often made unsafe and the National Cemetery is under threat of being washed away.

Since torrential rainfall in 2020, one-third of the park remains closed to visitation, deemed unsafe by park authorities. Thanks to the advocacy of American Battlefield Trust members and allies, progress is being made, but more is needed. We hope significant improvements to Vicksburg’s historic landscape can repair the park before it is irreparably damaged. By contacting Congress and speaking to local officials, our members have helped to preserve the memory of Vicksburg for generations to come. But there is still work to be done!

Earthwork maintenance is an evolving science that balances the needs of public interpretation and historic preservation. Before more modern studies, many parks simply rebuilt the earthworks that dominated their landscapes. These earthworks could be trampled upon without fear of losing a historic resource. But science has changed, and the reconstructed earthworks in many parks are becoming historic structures that tell the CCC’s story in their own right. Now, the best practice is to let the earthworks be OR give them a native grass cover to prevent erosion and lessen the impact of visitors’ stomping feet.

Remember: Enjoy the park, and keep off the earthworks!

Related Battles

182

300

12,500

6,000

4,910

32,363

8,150

3,236

1,057

1,900

17,000

13,000

4,150

1,750