Hunting for Provisions

American bison hunters at camp with stretched and drying hides, 1874.

Across the United States people are donning bright orange hunting gear, gathering with their family or friends, and enjoying one of humanity’s oldest sporting pastimes. Though the game on offer varies state-to-state, fall is generally the most popular hunting season in the United States. Deer, duck, turkey and more are hunted after the summer breeding season ends – in this way the population has already reproduced and hunting can happen sustainably. This was not always the case, however, and during the 19th century, hunting and plunder of local game could be a tactic of war.

Migratory Mouths: Hunting by the Army during the Civil War

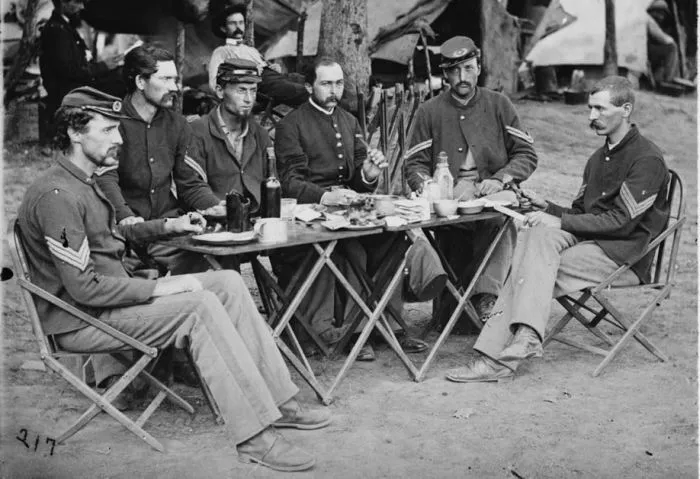

While not originally purposeful, both Union and Confederate forces would routinely hunt areas they passed through completely bare of game animals. This was largely due to the abject lack of reliable supply chains and appetizing food for both armies. Diary entries, letters, and testimonies abound from soldiers describing the food on either side as bland at best and inedible at worst.

Facing this harsh life in camp, soldiers on the march would take any opportunity to hunt. One sailor during the siege of Vicksburg recounted a tale where weapons of war were used for a winter’s goose chase; “It occurred to me that here was a chance to lay in some fresh provisions, and, asking the captain’s permission to fire one of my twenty-four-pound bow howitzers at this flock of birds...” The soldier recounted cheerily at the disbelief of his fellow veterans during post-war gatherings, “I have often told this story at dinners of naval veterans, etc., but always prefaced it with the statement that ‘I once killed forty-three geese and ducks with one shot’.”

Humorous anecdotes about scoring fresh goose aside, the reality of this practice hit home in the South, which began experiencing food shortages mid-war. The same soldier remarked that just days before the goose hunt, while stationed in post-surrender Vicksburg, he had seen the inhabitants reduced to subsistence primarily on mule meat.

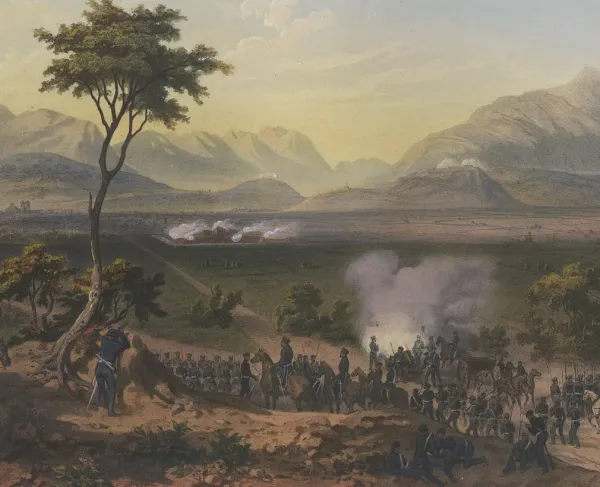

Shenandoah, Bloody Autumn and The Buffalo

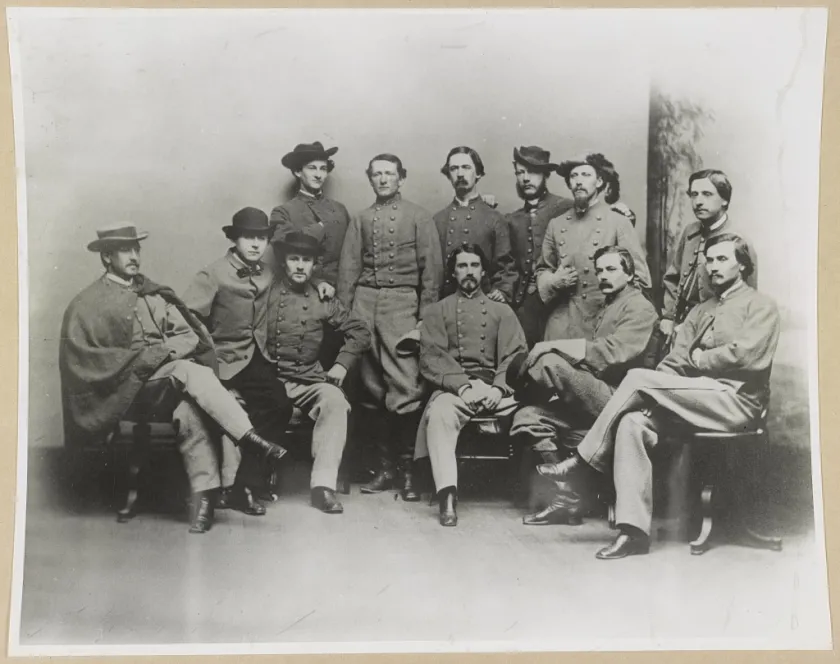

But the tactic of hunting as pillage really took shape, under Gen. Phillip Sheridan and his scorched earth tactics during the fall of 1864 within the newly minted Army of the Shenandoah. Under the direct instruction of their commander, Sheridan’s soldiers were dispatched all across the Valley to hunt, burn, and destroy all useful provisions that Confederate Gen. Jubal Early’s command could use.

This tactic was also intended to counter Confederate operations by the famed guerilla, Col. John Singleton Mosby. Mosby’s Rangers, as they were known, had been a terror for Union supply lines throughout the entire war. Operating behind Union lines with smaller forces, they lived off the local crops – either stolen or provided by sympathizers – and local game. The destruction of crops and mass culling of animals limited Mosby's ability to harass Federal supply trains, however, he never formally surrendered

The lessons learned by Sheridan fighting guerillas in Virginia were adopted by his U.S. Cavalry troops charged with the protection of western territory after the Civil War’s conclusion. Knowing that American Indian populations in the Great Plains were heavily dependent on buffalo, cavalrymen regularly drove the once prodigious herds into the traps of hunters. As the Smithsonian describes, Sheridan “took to his task much as he had done in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War, when he ordered the ‘scorched earth’ tactics that presaged Sherman’s March to the Sea”.

From Wartime Hunts to Peaceful Pastimes

Today, of course, the Bison population has recovered. Due to the preservation and reintroduction efforts of many local, state, and national land trusts, game animals familiar in the 17th and 18th century have been brought back for hunters to enjoy today. It is through the efforts to conserve habitat and species that today we can throw on our orange vests and hiking vests and enjoy the same wild lands rode by Sheridan’s cavalry long ago!