This iconic National Geographic photo captures the now demolished Pizza Hut at Franklin Battlefield, a stark reminder of the threats battlefields face from unchecked development.

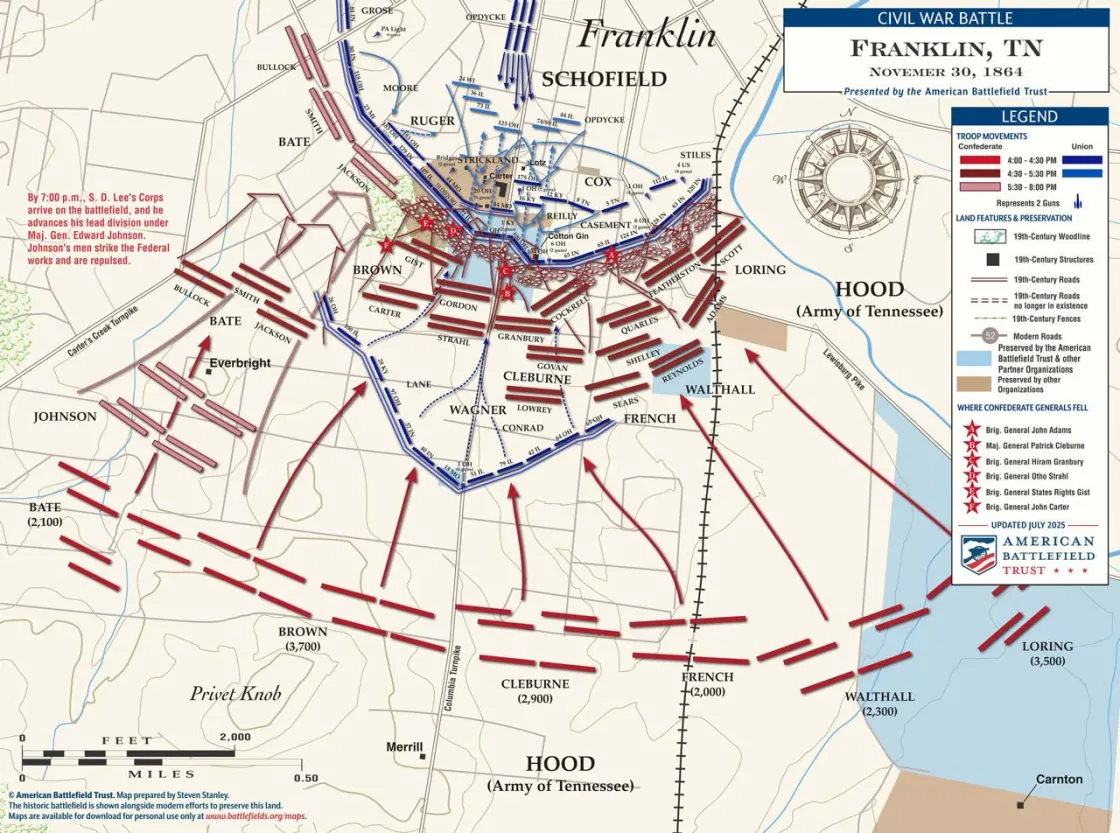

In the early 1990s, there was little in the town of Franklin, Tenn., to signal that it had borne witness to one of the most spectacular and horrific battles of the Civil War. The vast, open plain, two miles wide, where 20,000 Confederates made a futile charge into a maelstrom of shot and shell on November 30, 1864, had long since been crisscrossed by city streets and covered by homes and businesses.

Two antebellum homes were available for heritage-minded tourists, noted as much for their stately architecture as any Civil War connection. Along Columbia Avenue, the Carter House, once directly behind Union lines, retained its bullet-riddled outbuildings; just outside town, Carnton, the McGavock plantation home, stood watch over a cemetery the family created to contain the remains of 1,500 Confederate soldiers killed in the battle.

Franklin, with its frontal assault larger even than Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, was a devastating Confederate defeat, best forgotten in the South. Between 1899 and the late 1930s, a series of proposals to create a federally managed battlefield park went nowhere. Instead, the steady growth of a town within commuting distance of Nashville, slowly consumed the historic landscape, but for the two homes and two city parks that nodded to the battle’s legacy: Winstead Hill Ridge, where Confederates formed before the assault, and Fort Granger, a Union-built fort not even on the battlefield.

Since the 1990s, however, Franklin has undergone a remarkable transformation. The city’s heritage-minded leaders, in partnership with the American Battlefield Trust, local preservation groups and state and federal governments, have pioneered a dramatic new strategy that goes beyond battlefield preservation, reclaiming the lost battlefield from underneath a century of development. Lot by lot, parcel by parcel, they have been acquiring battlefield properties, removing the modern structures and restoring the land to its wartime appearance.

The first modern preservation project came in 1996, when the Heritage Foundation of Williamson County, with Trust assistance, purchased 57 acres at Roper’s Knob, but this was still outside the main battle area. Work in the heart of the battlefield began with the same group’s 1997 purchase of the “Blue House,” thought — and subsequently proven by archaeology — to stand where the Carter House cotton gin, once at the epicenter of the attack, but long since lost, had once been. Meanwhile, Carnton, too, underwent a renaissance. The mansion was meticulously restored in the 1990s and took on national significance with the publication of the New York Times bestselling novel, The Widow of the South, a fictionalized account of Carrie McGavock’s crusade to create the Confederate cemetery and remember the lost.

In June 2001, a group called Save the Franklin Battlefield purchased the 3.22-acre Collins Farm, which was a killing ground in the battle as a division of Confederates charged across it under intense Union fire. But that was just the beginning. Since then, a remarkable coalition of preservation groups have worked, both independently and jointly under the banner of “Franklin’s Charge,” to methodically buy and restore a string of properties where the most furious fighting took place. It brought together at least seven local organizations, including the Heritage Foundation, the STFB, Carnton and the Carter House, all closely allied and aligned with the Trust at the national level.

Franklin’s Charge “is probably the most significant and certainly the most viable local preservation group — true preservation group — in America,” said Trust President emeritus Jim Lighthizer at the height of their advocacy. “They're creating a critical mass out of something that was gone and couldn’t come back. And it is a miracle.”

This cohesive approach attracted government support. The City of Franklin long ago revitalized its historic downtown and invested with the preservation groups in securing battlefield land and building a destination for visitors. The city’s strong commitment to its heritage has made it one of the most popular and attractive small-town destinations in Tennessee.

The largest-scale victory at Franklin came in the Widow era, as the preservation community rallied to protect 110 acres near Carnton, now the city’s Eastern Flank Battlefield Park. But that was the last large-scale acquisition; efforts have since focused on through the battlefield’s heart, moving one lot at a time to take down a pizza parlor, a strip mall, a flower shop and several other single-family homes.

In 2005, the community came together to demolish a Pizza Hut that sat on the very spot where Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne, the “Stonewall of the West,” fell during the Confederate assault. The ill-sited fast food chain had been pictured in a National Geographic article on preservation movement and become a symbol of the “lost battlefield.” The site, notable for its pyramid commemorating Cleburne’s death, has since become central to the emerging battlefield park.

Piece by piece — two acres here, a half-acre there — the puzzle at Franklin has come together. All told the Trust has participated in 15 transactions at the site, totaling 182 acres. With our partners, we’ve filled in the gaps, creating a meaningful interpretive experience where there had once been a commercial strip at the edge of a residential neighborhood.

Today, Franklin is a major Nashville suburb with a thriving downtown that’s embraced its historic past. However, development threats persist, and preservation work is still ongoing. In 2025, 20 years after the Pizza Hut demolition, the Trust helped to preserve two tracts just south of the historic Carter House, filling in critical preservation gaps in the area.

Franklin stands as a national model for battlefield reclamation. What was once written off as lost ground has been reborn as a landscape appropriately honoring the struggle and sacrifice that took place on that land in 1864.

Related Battles

2,326

6,252