Petersburg Breakthrough Battlefield, Va.

Unrelated to the Army Chief who shared his last name, Maj. Gen. Lewis Grant demonstrated tactical leadership often lacking during Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s year of combat with Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. A Medal of Honor recipient for leadership under fire during the Chancellorsville campaign, the commander of the Vermont Brigade provided a welcome change of pace to the unimaginative sluggishness that characterized many of the previous attempts to capture Petersburg. General-in-chief Grant often delegated battlefield plans and decision making to his subordinates. The frequency with which they let him down would have justified a more hands-on approach, but no such meddling would be necessary on the Sixth Corps’ front.

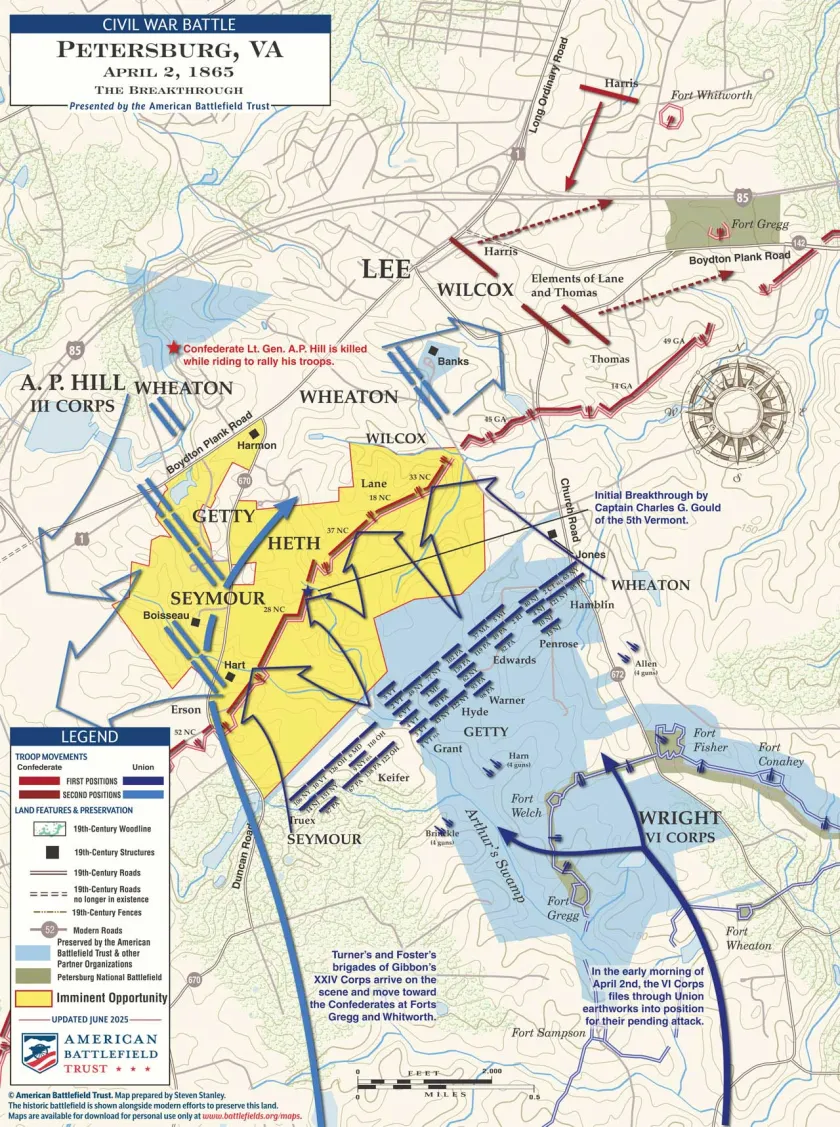

By late March 1865, Lee’s army stretched itself out to protect 35 miles of fortifications. Union forces paralleled that wide front from Richmond down to Petersburg. The lines circled that city to the south and continued onward down Boydton Plank Road until it met Hatcher’s Run. The Union spring campaign called for cavalry and two infantry corps to cross that stream past the Confederate line and then turn west to cut the Boydton Plank Road. From there, they would continue onward to either cut the South Side Railroad — Petersburg’s last direct supply line — or engage and destroy whatever force was sent to impede their progress.

Those who remained in the primary entrenchments maintained standing orders to assault the Confederate earthworks to their front should the Confederates weaken themselves there to reinforce other areas. Aware of that possibility, Lewis Grant scanned the potential battlefield for weak spots. His curiosity was rewarded with the discovery of a small ravine containing the headwaters of Arthur’s Swamp, which pooled behind the Confederate works before gently meandering southeast toward the Union line. Grant informed his superiors, including corps commander Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, that he believed this ravine was the key to the landscape. When Wright received orders on April 1 to launch an attack the following morning, he already had a working plan in place. Ten North Carolina and Georgia regiments manned the earthworks opposite Wright, and the Sixth Corps commander employed every measure he could fit into his orders to maximize the significant numerical advantage he already possessed. Using the cover of night and an artillery bombardment all along the Petersburg front, Wright deployed nearly the entirety of his 14,000 strong corps just behind his picket line.

The Vermonters centered this formation in the Arthur’s Swamp ravine and were to use the terrain as a physical guide toward the Confederate line in their pre-dawn assault. Grant furthermore instructed his six colonels of secondary objectives for each of their regiments once they reached the Confederate position and encouraged them to share encouragement and specific roles with their own subordinates. The 5th Vermont Infantry, Grant’s former command, had the honor at the front and center of Wright’s wedge formation. Seven more brigades stacked up in echelon to the left and right of the Vermonters. Pioneer detachments were to precede the attack to cut gaps through obstructions. The storming columns were ordered to not pause and return fire, lest that arrest the momentum of the attack before it could reach its objective, which was to be carried at the point of the bayonet.

Despite Wright’s best efforts to keep the pending attack hidden from the enemy, alert Confederate pickets sensed something occurring in the darkness to their front and began firing blind shots toward the massed bluecoat infantry. Union commanders prevented their men from giving away their position and intentions, but the force began suffering casualties with the attack still hours away. Two regimental commanders did not survive the pickets’ fire and Grant, too, soon fell with a bullet wound to his head and was taken to the rear.

The signal gun fired at 4:40 a.m. After some brief confusion, the Vermonters sorted themselves out and rushed up the ravine to the Confederate position half a mile away. They swooped over the enemy rifle pits without pausing to stop and continued pushing onward. Company H occupied the left side of the Fifth Vermont’s line at the head of the attack. A misunderstanding in the darkness caused them to veer up a secondary branch of Arthur’s Swamp that did not fully continue to the Confederate line. Capt. Charles Gould paused in this defilade to gather as many of his men as he could immediately locate. Though temporarily safe from the enemy’s fire, he determinedly rose up and pressed ahead. Reaching the Confederate earthworks and scaling its imposing wall, Gould suffered severely in intense hand-to-hand combat as the first man over the top. His company meanwhile raced forward to join him.

Attacking waves on both sides rapidly expanded this breakthrough. Pushing further into the camps, they swung down line and rolled the Confederate position all the way to Hatcher’s Run.

Lewis Grant rejoined his brigade during this latter phase of the battle with his head wrapped in a bandage. The confidence and clear instructions he provided his men from the planning stages onward likely influenced the outcome and overcame his temporary absence. A plausible “what if” scenario exists in which Company H and other Vermonters paused to return fire from vulnerable positions in front of the Confederate line. That tempting alternative to storming over fortifications with the bayonet could have contagiously stalled and minimized the impact of what has been justifiably deemed the most consequential attack of the Civil War.

Confederate Third Corps commander Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill held responsibility for the lines broken by Wright’s men that morning. The lieutenant general had just returned to his post from medical furlough and kept his headquarters on Petersburg’s western outskirts three miles from the assailed point. He spent a restless night listening to the widescale artillery bombardment and learned early in the morning of the Union IX Corps attack on the city’s southeastern defenses. Saddling up ahead of his staff, he sped a mile and a half west toward Lee’s headquarters at Edge Hill.

Hill learned along the way that his own lines were under attack, yet he lingered at the Turnbull House until a member of Lee’s staff interrupted the discussion with an update on the severity of the Federal attack. Taking just four companions, Hill immediately rode south with the intention of reaching division commander Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s headquarters at the Pickrell House. He was unaware that post had already been evacuated, but evidence along his route suggested the futility of the attempt. The riding party paused to water their horses in Cattail Run, where they were surprised by a pair of Union soldiers who had adventured too far from the breakthrough.

Hill’s small escort burst forward to protect the general, and one of them departed to lead their new prisoners back to Edge Hill. Shortly thereafter, Hill dismissed two others with instructions for a friendly artillery battalion he spotted parked along Cox Road. Only Sgt. George Tucker remained with Hill as he continued along Cattail Run. Tucker claimed the general acted strange as they observed Union soldiers in force along the Boydton Plank Road in the vicinity of the Pickrell House. Hill insisted on continuing the mission despite their presence. They rode up from the creek toward the road but soon noticed two Union infantrymen working their way out from the lowlands a bit further upstream.

Corp. John Mauk and Pvt. Daniel Wolford of the 138th Pennsylvania had participated in the successful charge that morning, crossing through the Confederate line just south of where Gould first struck it. The pair enthusiastically continued onward to wreck a few rails of the South Side Railroad before turning back to rejoin their comrades. They noticed the Confederate riders at the same time they were spotted and took shelter behind a tree. Tucker spurred his horse forward to capture them. The Pennsylvanians replied with a volley, missing the courier but killing Hill instantly.

Accounts of Hill’s death took their cue from Tucker, who depicted Hill as carelessly seeking out a confrontation. Hill’s staff, however, suspected the courier crafted his story to absolve himself of responsibility for the prominent casualty. Several decades later, Hill’s nephew claimed the general had vowed he did not wish to survive the fall of Richmond. That statement is frequently used to explain Hill’s erratic behavior, but the theory relies solely upon a secondhand quote far removed from the scene.

It is possible that Hill myopically believed that the only way to save Petersburg and Richmond was to rally what he could of Heth’s men. Determined to reach the division commander, the general gave little thought to his own safety. Circumstances dictated that he would not survive, but Hill’s lack of concern for his own well-being — oft criticized as it is to this day — would be likewise demonstrated on April 2 by both army commanders.

U.S. Grant relocated his headquarters during the spring offensive to Dabney’s Mill, south of Hatcher’s Run, where he managed the different elements of the operation. He remained there throughout the night of April 1–2, maintaining frequent communications with key components of the plan: President Lincoln, his army and corps commanders, the cavalry further to the west who had just fought at Five Forks, as well as William Sherman and generals elsewhere throughout the south wrapping up active campaigns to bring an end to the rebellion. Early the next morning, he received news of Wright’s breakthrough.

Grant looked to the relatively fresh Army of the James, positioned along Hatcher’s Run, for the final push to close in on Petersburg from the west. Two isolated Confederate forts — Gregg and Whitworth — served as the only secondary defenses in the wide space between A.P. Hill’s broken line and Petersburg’s inner defenses. Four Mississippi regiments joined the hodgepodge garrison of artillerists and Third Corps refugees there. Throughout the afternoon they held the Army of the James at bay. Grant, with his staff, meanwhile followed on the heels of this force before settling into a temporary headquarters at the Margaret Banks House, less than a mile from Fort Gregg. He sat down at a tree north of the house and continued sending and receiving dispatches.

Confederate artillerists noticed the large retinue and began shelling the position. As they started to close in on the target, several of Grant’s staff nervously encouraged him to seek shelter. The general ignored their pleas and continued his correspondence. Concluding a batch of messages, Grant stood up to assess the danger before ambling around to the other side of the house. Slight adjustments by the Confederate gunners would have significantly impacted what is otherwise recorded merely as an amusing anecdote about Grant’s stubborn fixation on the task at hand. The Union commander’s flippancy in the moment reflected his overall leadership style to put the bigger picture into place and trust that the smaller battlefield details could work themselves out.

Less than two miles away, Robert E. Lee was meanwhile losing himself in the minutiae. A.P. Hill’s final military order had directed William Poague’s artillery battalion to report to Edge Hill. Throughout the morning, these gunners served as the only organized force protecting army headquarters. Lee reportedly took time to ride among the batteries to offer encouragement and support. As Union infantry cautiously worked their way northward from the point of the Breakthrough, the Confederate commander spent a frustrating morning conversing by telegram with President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of War John Breckinridge. He advised them of his need to abandon Petersburg that night, which would force Richmond’s evacuation as well. The politicians’ response scolded the general for not giving them enough time to properly relocate the government from the capital. Lee furiously ripped that message to shreds.

The Confederate army commander planned to reunite the scattered refugees of his army at Amelia Court House, from where he would attempt to move into North Carolina and rendezvous with Gen. Joseph Johnston’s army. The decisiveness of the Union victory on April 2 enabled Grant to keep pace with Lee’s withdrawal, preventing the Army of Northern Virginia from turning south. Issues of supply, marching routes and orderly evacuation from Richmond further hampered the Confederate retreat. Yet, while his opposing commander sent messages in all directions from his post under fire at the Banks House, Lee appeared to welcome the distraction of personally assisting in the defense of his own headquarters.

Famously, the Virginian had previously responded to crisis by placing himself under fire and assuming the role of a subordinate several levels below his role as army commander. These “Lee to the rear” moments from the Overland Campaign repeated themselves once more outside Petersburg. The general prominently remained among the artillerists as they contested the Union troops creeping toward Edge Hill. Staff officers begged him to seek refuge within Petersburg’s inner defenses. Others boast that the commander was the last to leave the guns. These blurred lines of what constituted proper leadership on the battlefield perhaps kept Lee from focusing on the greater responsibilities that demanded his attention as the commander of an army clinging to its life. The decisive results of the Union attack on April 2, 1865, were the death knell of the Army of Northern Virginia; it survived just one more week until its surrender at Appomattox.

Related Battles

8,150

3,236

3,500

4,250