Petersburg Breakthrough Battlefield, Va.

In the predawn darkness of April 2, 1865, some 15,000 Union soldiers gathered in their trenches outside Petersburg. After 292 days of siege, they were readying for a general assault, the largest to date, designed to pierce the lines and open the road to Richmond.

Thirty-one Medals of Honor were presented for this push, known to history as the Breakthrough. The Army’s Medal was created by congressional legislation and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862. As the only official military medal available at the time to recognize heroism in the line of duty, it became an object of reverence.

These are the intertwined stories of four of those Medal of Honor recipients at the Breakthrough: John C. Matthews, Robert L. Orr, Charles G. Gould, and Jackson G. Sargent.

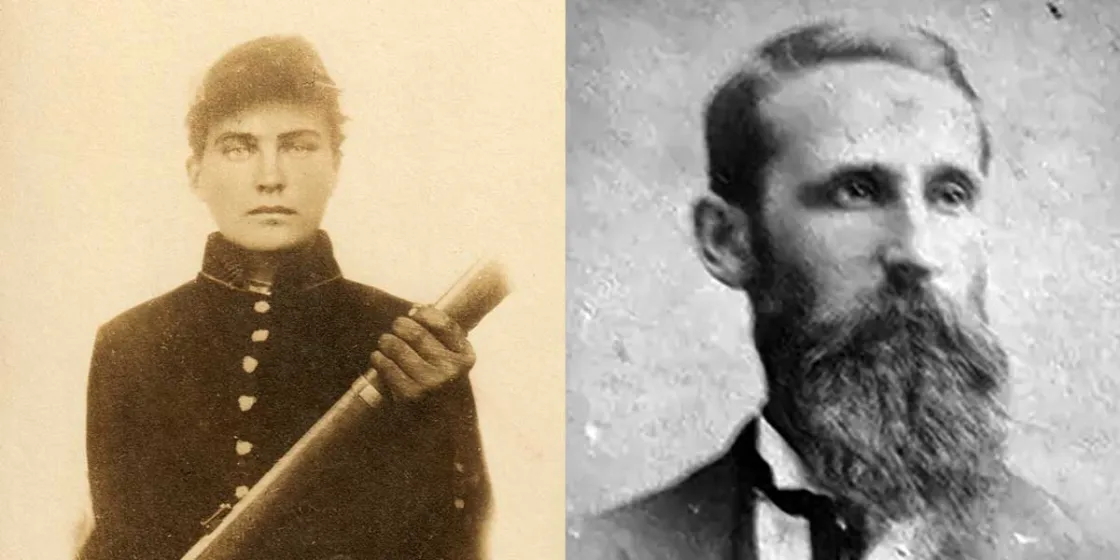

John Matthews and Robert Orr

John C. Matthews and Robert L. Orr both served with the 61st Pennsylvania Infantry. Both received the Medal of Honor for keeping the colors flying during the heat of battle when the color sergeant no longer could.

During the fighting at the Breakthrough, the color sergeant was shot down, so Matthews voluntarily hoisted the regimental and state colors. Orr, in command of the regiment, then took the state flag from Matthews. Together, they “ran along the line waving the colors, rallying the men for the last rush.”

The pair’s origins were disparate and ultimate fates divergent, but in through that remarkable moment, they are forever bound together.

John C. Matthews was born in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, in 1845, the eldest child of William and Susan (Brown) Matthews. He grew up on the family farm in East Mahoning, Pennsylvania, a rural community where the population has never exceeded 1,300 souls according to the U.S. Census. His future wife, Asenath Work, grew up in the same community. Matthews may have gone by his middle name, Calvin, given the way his death was reported in local papers.

His family had a history of military service. His mother’s grandfather served in Revolutionary War and his paternal grandfather served in the early Indian Wars and the War of 1812. Matthews himself served two enlistments during the Civil War: first nine months in the 135th Pennsylvania Infantry, then in the 61st Pennsylvania from December 1863 until his discharge at the close of the war as a sergeant.

Matthews married after the war and moved to Pittsburgh, to work as a clerk in the railroad business. At one point, the family rented a home at 365 Princeton Place.

He and his wife had five children, three of whom lived to adulthood. As the couple aged, they moved in with their adult children. Matthews’ last address was at 470 Carroll Street in Akron, Ohio, the home of their eldest daughter Clara and her husband Rev. Dr. Orin Keach.

Matthews died there in 1934. For some time, it was believed that he was buried at Dayton National Cemetery in Dayton, Ohio, but further research has shown he is actually buried at Homewood Cemetery in Pittsburgh, alongside other family members. His Medal of Honor is in the care of the Soldier & Sailors Memorial Hall and Museum in Pittsburgh.

His rented home in Pittsburg is gone. In its place is a row of modern triplexes. Similarly, the house in Akron has made way for a fraternal house associated with the University of Akron.

Robert L. Orr was born into a Philadelphia merchant family in 1836. A pattern of familial loss followed him throughout his life. He was only around five years old when his father, William H. Orr, died. The family dry-goods store at 158 N. 15th Street was left in the hands of his father’s trusted storekeeper, an immigrant named Giacinto de Angeli, with the intent that it would pass to young Robert when he came of age.

By 1850, Orr was living with his paternal grandmother and aunt (both named Ann) while his mother and younger sister lived with maternal relatives. His mother, Justina, passed away a few years later in 1853. Orr’s sister, Elizabeth, moved in with the paternal relatives from then on.

Orr first served a three-month term as a first lieutenant in the 17th Pennsylvania in 1861. After he was mustered out, he helped organize elements of the 23rd Pennsylvania, which was later redesignated the 61st Pennsylvania. By the time he left the service, he was a colonel.

After the war, Orr took control of the family dry-goods store, as intended. He married Mary T. Clemons, and the pair had two sons in three years before Mary died. By 1870, the Orr household on Winter Street in Philadelphia consisted of his Aunt Ann, his sister Elizabeth, his two sons, and a servant. Orr himself died in 1894; his last home of record was at 1740 N. 15th Street. He was laid to rest in Philadelphia’s Lawnview Cemetery.

The traces of Orr’s life in Philadelphia are no longer there. The dry-goods store, located on property that backed up to the historic Friends Meeting House, is now a modern expansion of the Meeting House called the Friends Center. The area where he lived in during the 1870s on Winter Street was mostly demolished in the mid-20th century to widen a nearby thoroughfare. His last home’s location is now a parking garage for Temple University’s basketball and event arena.

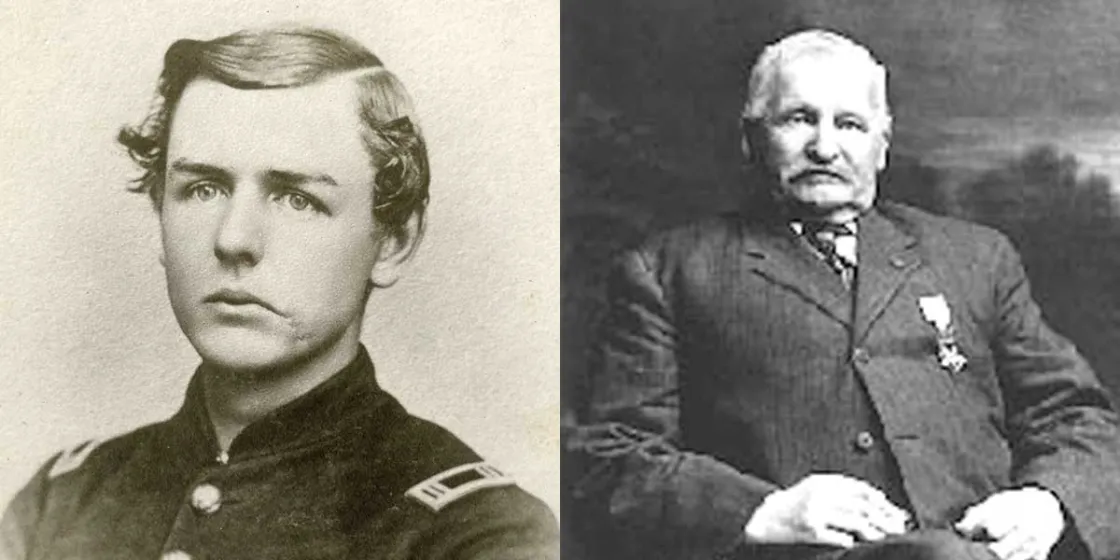

Charles Gould and Jackson Sargent

Charles G. Gould and Jackson G. Sargent both came from Vermont farming families. When Gould went first over the Confederate works, Sargeant was close behind him with the national colors. After the war, Sargent and Gould spent weeks at a time within a few score miles of each other. but they did not cross paths again until 1913, brought together through the efforts of another Civil War veteran who offered up his home for the reunion.

Charles G. Gould lived on the family farm in Windham, Vermont, when the Civil War started. He left behind his parents, James and Judith, and two brothers to enter service as a 17-year-old private, rising to the rank of brevet major.

During his brave charge against the enemy at the Breakthrough, Gould suffered several wounds, any of which could have easily been fatal. He had passed through a narrow opening in the Confederate defenses, directly into the enemy lines. The Confederates, not taking kindly to the sudden appearance of this Union soldier, set upon him quickly. A musket fortunately misfired, but a bayonet pierced through his mouth and lower left jaw and a saber jammed into his upper spine. Somehow, Gould survived the damage and was able to retreat to the rear and report the need for reinforcements.

In letters home from the hospital two days later, Gould wrote that “the wound in my back is nothing at all as it hit the backbone and stopped. The cut on my head is very slight and in fact all my wounds are … I am feeling firstrate … Don’t worry about me for I never felt so well in my life.” His was “only sorry that I was wounded before I got to Richmond.”

Following the war, he was offered a position as a clerk at the U.S. Pension Office in Washington, D.C., in part because of his heroic actions at Petersburg. He continued his civil service with the District’s Water Registrar and the U.S. Patent Office, where he retired as principal examiner.

During that time, Gould attended Columbian University (now George Washington University) and married twice. His first marriage in 1871 was to Ella Cobb Harris of Vermont, with whom he had two daughters. Sadly, all three had passed away by September 1890. He then remarried his first wife’s cousin, Frances Lucy, in 1893 and had a third daughter, Margaret.

Gould and his family summered in Cavendish, Vermont, at Frances’s family home at 2124 Main Street, well away from the bustle of the District of Columbia. When he retired about six months before his death, the family made the move permanent, and Mrs. Gould purchased the home. Gould died in December 1916 and was buried at Windham Central Cemetery in Windham, Vermont.

Gould left behind a rather impressive physical legacy. His personal archives at the Special Collections Library at the University of Vermont; his uniform, pistol and Medal of Honor at the Pamplin Historical Park Museum boarding the Petersburg Battlefield; and his last home in Cavendish still stands to this day.

Jackson G. Sargent was one of at least eight children born to Jeremiah Sargent and Sophronia Robinson. He grew up working his family’s farm on what locals refer to as “West Hill” in Stowe, Vermont, according to Barbara Baraw of the Stowe Historical Society.

Sargent was 19 when he mustered into Company D of the 5th Vermont Infantry. He served the entirety of the Civil War and mustered out as a lieutenant.

For years, there was debate about who planted the first colors on the Confederate works during the Breakthrough, but Gould, as the first through the works, put that speculation to rest in 1913 in a newspaper piece that gained wide traction. He wrote that, “I know, absolutely and positively, that before leaping into the works Sergt. Jackson Sargent joined me on the parapet with one of the stands of colors belonging to the 5th Vermont regiment, and I, therefore, feel justified in asserting that the colors of the 5th Vermont were first on the works.”

After the War, Sargent returned to Vermont, married Carolina “Carrie” Harlow in 1866, and had three sons. His wife died in 1895; his eldest son followed her not long after. Sargent remarried, to Clara Slayton, in 1899.

He took up farming in and around Stowe, at one point running a farm in Hyde Park, about 12 miles north of his birthplace. He was back in Stowe by 1920 and told the census taker he lived on a dairy farm, even though his address on Maple Street sat up against a mountainside on the main road through town and was clearly not big enough for such an operation. Sargent died there in 1921 and was buried in River View Cemetery in Stowe. His home on Maple Street still stands.

When the conflict ended, each of these soldiers went home to their families, their jobs and their everyday existence. They built lives. Maybe the memories of their time in war replayed for them regularly. Maybe they never thought of it again.

But their legacy endures not only in their Medal of Honor actions, but also in the echo of the physical places they lived and walked and breathed and fought.

Orr’s and Matthews’ moment of valor occurred on land already preserved by the American Battlefield Trust; the Trust is currently raising funds to permanently safeguard the location of Gould’s and Sargent’s.

Merchant. Farmer. Railroad Clerk. Pension Examiner. All also soldiers during the Civil War. And their legacies all deserve protection.

Related Battles

8,150

3,236

3,500

4,250