The Battle of Fredericksburg was one of the most embarrassing Union defeats of the war, but the details of the battle are less well-known. Here are some facts to help shed a little light on the battle for newcomers and test the knowledge of veterans.

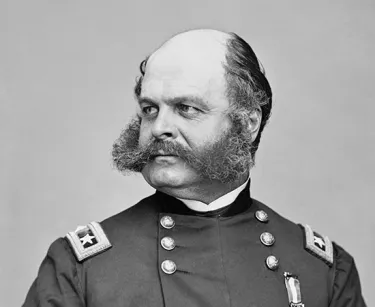

Fact #1: Union General Ambrose Burnside did not want command of the Army of the Potomac.

After Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's failure to follow up on his victory at the battle of Antietam, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was ordered to replace him as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside was reluctant to accept this post, believing that he was not qualified for such a large command. In fact, he had previously turned down two other offers of promotion from Lincoln.

This time Burnside felt that his duty required him to accept the President's promotion. As he wrote a colleague: “Had I been asked to take it I should have declined; but, being ordered, I cheerfully obey.” Another factor in Burnside’s decision to accept the post was the fact that Burnside wanted to prevent his subordinate, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker (Lincoln’s second choice for the post), from taking command, as Burnside held a low opinion of Hooker.

Burnside finally took command of the army on November 10, 1862, and began devising a bold plan to capture Richmond.

Fact #2: The Union crossing at Fredericksburg was delayed by a lack of portable pontoon bridges.

Burnside’s plan had real promise. He reached Fredericksburg — a small city on the Rappahannock River — long before Robert E. Lee's army. With few Confederates holding the city, Burnside could easily have captured it and marched on Richmond. Lee commanded the only sizeable force that could oppose him, but his army was divided: Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Corps was a week's march away from Fredericksburg in the Shenandoah Valley.

Burnside's speed and superior numbers were meaningless without the pontoon boats that he needed to cross the Rappahannock River. Due to administrative problems, the first pontoons arrived a week after Burnside reached the North bank of the Rappahannock, and the Union general waited another two weeks before attempting to cross. The delay afforded Lee time to re-unite his army in strong positions west of Fredericksburg, but Burnside decided to cross the river at Fredericksburg anyway.

Fact #3: Fredericksburg hosted the largest group of soldiers to participate in a Civil War battle.

In the fall of 1862, Burnside’s army was 120,000 men strong and Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia held over 70,000 soldiers. Lee's army was initially divided into two groups, but by the time of the battle, he once again had his full force at his command. All told, 172,000 were actually available to the two commanders during the battle. By contrast, only 158,000 soldiers fought at Gettysburg in July 1863.

Fact #4: Union forces bombarded Fredericksburg with 150 cannons.

As Union engineers attempted to assemble the pontoon bridges on the Rappahannock, they were fired upon incessantly by Confederate sharpshooters positioned in buildings in town – preventing them from making progress on the bridges. In an attempt to suppress the sniper-fire, Burnside ordered Union artillery to bombard the town. The ensuing barrage damaged nearly every house. The shelling of Fredericksburg was arguably the first time a commander deliberately ordered a large-scale bombardment of a city during the Civil War.

One Union bystander described the violence: “Report followed report in quick succession – a number at a time seeming to be simultaneous – a heavy crashing thunder rolling over the valley, and up the hills by which it was flung back in deep reverberations; columns of smoke were seen to rise and bright flames were seen, a number of buildings being on fire.”

Fact #5: The Battle of Fredericksburg was the first opposed river crossing in American military history.

As Burnside grew desperate, he sent troops across the river in pontoon boats to establish a bridgehead and drive away Confederate sharpshooters. These soldiers came under heavy fire, but ultimately cleared away the snipers and enabled engineers to finish construction of the bridge.

Although the main Confederate force waited for Burnside’s army outside the city, Gen. Barksdale's Mississippi Brigade remained to resist the Union advance through town. The fighting which ensued in the streets and buildings of Fredericksburg was the first true urban warfare of the Civil War.

Fact #6: The famous attack on the Sunken Road was supposed to be a diversion.

Burnside planned to use the nearly 60,000 men in his “Left Grand Division” to crush Lee’s right flank while the rest of his army held the Confederate left flank in position at Marye’s Heights.

The Confederate infantry held positions at the base of the heights in an impromptu trench formed by a stone wall bordering a sunken road. Wave after wave of Federal soldiers advanced across the open fields in front of the wall, but each was met with devastating rifle and artillery fire from the nearly impregnable Confederate positions. All told, Burnside’s “diversion” produced around 8,000 Union casualties compared to 1,000 fallen Confederates.

Fact #7: Confederate horse artillery on the Union left flank caused the Federals to divert their largest division from the main attack.

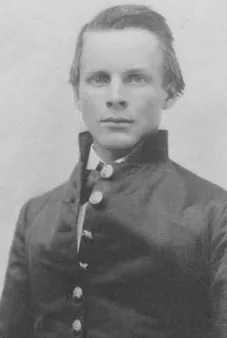

As Union troops assembled for battle on the morning of December 13, Maj. John Pelham sensed an opportunity to preempt the Yankee attack. He advanced two cannons to a shallow basin about one half mile beyond the Union army’s left flank, and opened fire around 10:00 a.m. The Federals had no idea what hit them. Many initially assumed the fire came from a confused Union gunner until Pelham unleashed his second round. Union batteries on this field and across the river returned fire, but Pelham’s small crew, masked by hedges and fog, proved elusive.

After one cannon was disabled and his ammunition began running low, Pelham finally disengaged and fell back to the Confederate line, having fought his guns for an hour. His feat impressed Lee, who referred to the artillerist in his report as “the gallant Pelham.” Pelham’s attack both delayed the Union advance and diminished its size: an entire Union division was repositioned to protect the army's flank, effectively removing it from the battle.

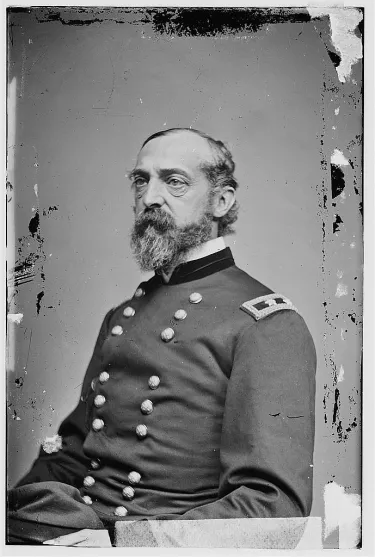

Fact #8: The Union army broke through Confederate lines near Prospect Hill.

South of Marye’s Heights, Stonewall Jackson's 37,000 men occupied wooded high-ground with open farmlands stretching below them for nearly a mile and a railroad embankment providing them with natural breastworks. A 600-yard swampy marshland that the Confederate commanders considered impassible divided Jackson's lines.

Following the path of least resistance, members of Maj. Gen. George Meade's division of Pennsylvania Reserves through this swampy bog during the battle. Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg's Brigade, which was waiting in reserve behind the lines, were the only Southerners in the area. Two of Meade's regiments caught Gregg by surprise, and routed the whole brigade. Simultaneously, Maj. Gen. John Gibbon's division attacked across a field next to the swampland, driving back a brigade of North Carolinians defending a railroad grade. The two attacks broke the Rebel line and would have rendered the entire Confederate position untenable if enough Union reinforcements were committed to the attack.

Fact #9: A timely counterattack saved the broken Confederate lines, and gave the area its nickname.

As the fighting continued, the Northerners began to run out of ammunition, and several of their most important officers were incapacitated. Without reinforcements, the attacks ground to a halt. Jackson, on the other hand, received reinforcements quickly, and his troops surrounded the Gibbon's men on three sides – leaving many of them exposed in the open field. The Federals were forced to fall back, and the Confederates recaptured the railroad embankments.

The carnage was devastating. 9,000 men—5,000 Northerners and 4,000 Southerners—fell dead or wounded in the fighting; a Confederate lieutenant wrote that the dead lay “in heaps.” In the field, nicknamed “the Slaughter Pen” by soldiers who witnessed the carnage, the Union lost its best chance for victory at Fredericksburg.

Fact #10: The purchase of the Slaughter Pen Farm was the most expensive private battlefield preservation effort in American history.

When development threatened the 208-acre Slaughter Pen Farm, the Civil War Trust, partnering with Tricord, Inc., SunTrust Bank, and the Central Virginia Battlefield Trust, launched a campaign to preserve this hallowed ground. The Civil War Trust also worked with the Department of the Interior and Commonwealth of Virginia, which provided matching grants to acquire the property. In 2006, the Trust and its partners purchased the Slaughter Pen Farm for $12 million.

Bonus Facts:

- The fighting that took place in the houses and streets of Fredericksburg was the first major instance of urban warfare in the Civil War.

- Bitter Union troops set about pillaging the town after the Rebels were finally defeated on December 11. As one civilian wrote: “Every unoccupied house was plundered and every piece of furniture destroyed…. They committed every species of outrage.” Many historians consider the 1862 sacking of Fredericksburg to be the worst instance of looting in the war up to that point.

- 15 Union brigades participated in charges against Marye’s heights, but not a single unit reached the stone wall.

- While watching the fighting at the Slaughter Pen from his command post, General Lee uttered his famous words, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”

- Moved by the cries of wounded Northerners wounded on the night of December 13, Sgt. Richard Rowland Kirkland of the 2nd South Carolina climbed over the stone wall the next day to provide water and comfort to many wounded Union soldiers – earning himself the nickname “Angel of Marye’s Heights” or “The Humane Hero of Fredericksburg.”

- After the battle, the Federals withdrew across the river to avoid being trapped, effectively relinquishing the gains they made by crossing the river.

- To reclaim his reputation and repair morale, Burnside led a failed winter offensive derisively called the “Mud March” a couple weeks after the battle.

- The City of Fredericksburg changed hands at least seven times during the course of the war.

- Renowned author Louisa May Alcott served as a nurse shortly after the battle of Fredericksburg. Her experiences with the wounded soldiers from the battle are included in her book Hospital Sketches.

- Five months after the battle, the Second Battle of Fredericksburg took place on May 3, 1863 as part of the Chancellorsville Campaign.

Learn More: Fredericksburg

Related Battles

12,500

6,000