Ambrosio José Gonzales

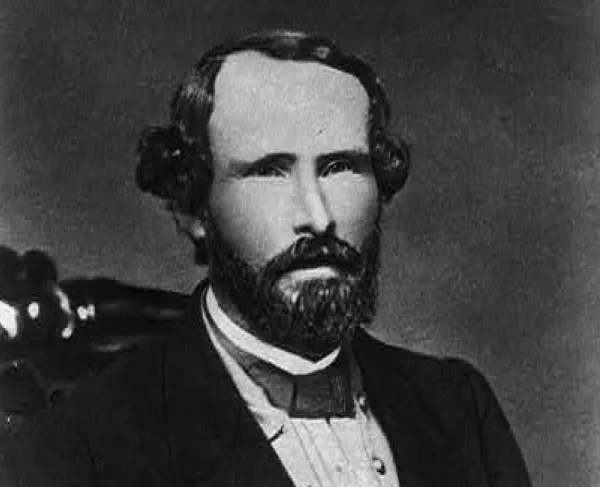

From Cuban freedom fighter to artillery colonel in the Confederate Army, Ambrosio José Gonzales’s life was marked by revolutionary fervor and military ambition. His journey reflected Cuba’s desires for independence from Spain and the United States’ political divisions.

Gonzales was born on October 3, 1818, in Matanzas, Cuba. From an early age, Gonzales received a good education, including attending the French Institute, a semi-military school, in New York City. There, he was a classmate of future Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard. Returning to Cuba, he graduated from the University of Havana in 1839 with degrees in arts, sciences, and law. He became a professor and was fluent in multiple languages.

Gonzales became an advocate of Cuban independence. For 400 years, Cuba had been a Spanish colony, and over time, many Cubans had become disillusioned with the colonial government. In 1848, he joined the Havana Club, a secret organization advocating for Cuba's annexation by the United States. The club believed that joining the United States would free Cuba from corrupt Spanish colonial rule, safeguard slavery, and strengthen the island’s economy. Many Americans, especially Southerners, welcomed this idea as an opportunity to expand slaveholding territory. Gonzales served as the rebels' de facto ambassador to the United States, meeting with influential figures like President James K. Polk and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis.

Gonzales joined filibustering expeditions to liberate Cuba. These military operations were aimed at conquering, overthrowing, or increasing US influence in Latin American countries. Despite the repeated failures of these attempts and legal challenges for violating neutrality laws, Gonzales did not quit. In 1849, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. Three years later, he settled in Beaufort, South Carolina. There, he married South Carolinian Harriet Rutledge Elliott; together, they had six children.

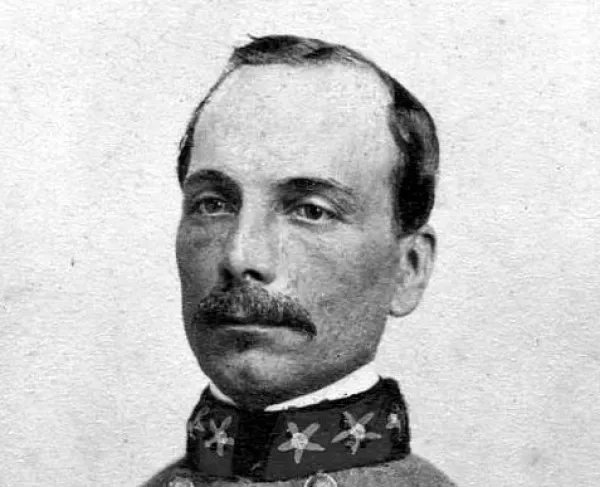

As some southern politicians anticipated a secession crisis, Gonzales leveraged his military background and connections. In the 1850s, he worked as a sales agent for firearms manufacturers, selling the LeMat revolver and the Maynard Arms Company rifles to Southern state legislatures. After South Carolina’s secession in December 1860, he volunteered for the Confederate Army, joining the staff of his former schoolmate, General P.G.T. Beauregard. Gonzales was active during the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, earning commendation from Beauregard for his "indefatigable and valuable assistance."

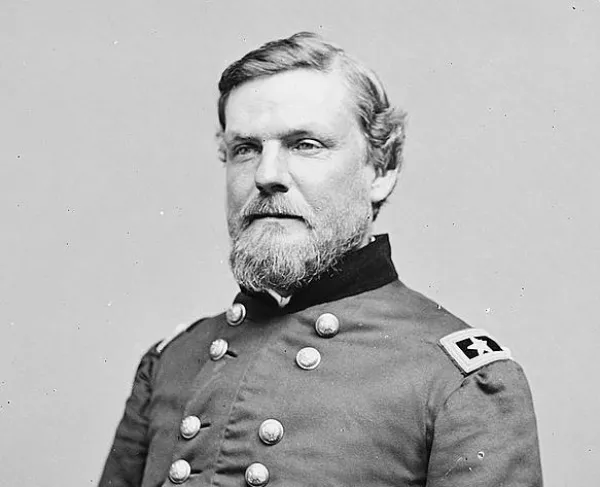

He quickly rose through the ranks, first as a special aide to the governor of South Carolina, then commissioned as a Lieutenant Colonel of artillery. By 1862, he was promoted to colonel and appointed Chief of Artillery for the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, serving under General John C. Pemberton. Gonzales played a significant role in defending the Carolina coast. His effective use of heavy artillery countered Union gunboats. His military skills were further demonstrated at the Battle of Honey Hill on November 30, 1864. In this battle, he commanded the Confederate Artillery, which contributed to a Southern victory.

Despite his competence and Beauregard and Pemberton’s recommendations for promotion to brigadier general, Confederate President Jefferson Davis repeatedly denied Gonzales’s advancements. Davis disliked Beauregard, and he perceived Gonzales as unsuitable for higher command. Davis cited his past filibuster failures and poor relationships with other Confederate officers as evidence, denying Gonzales’s requests for promotion six times.

After the Confederacy's collapse in 1865, Gonzales faced severe financial hardship. Like other Southerners, he struggled to rebuild his life and provide for his family. He attempted various vocations, but all proved unsuccessful.

In 1869, he moved his family to Cuba, where his wife, Harriet, died of yellow fever. Gonzales returned to South Carolina with four of his six children, leaving two temporarily in Cuba. His children were raised by their grandmother and aunts at the Oak Lawn plantation. The Reconstruction Era continued Gonzales's financial struggles, leading to strained family relationships. Despite their difficult upbringing, two of Gonzales's sons, Ambrose E. Gonzales and Narciso Gener Gonzales, became prominent journalists. They co-founded The State newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, in 1891, which became an influential voice in the state's politics and advocated for social reforms.

Ambrosio José Gonzales spent his later years struggling with illness, living in various locations including Cuba, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. He died on July 31, 1893, at the age of 74. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City. He passed away just five years before the Spanish-American War finally secured Cuba's independence.

Gonzales’s life is extensively documented in Antonio Rafael de la Cova's biography, Cuban Confederate Colonel: The Life of Ambrosio Jose Gonzales. Gonzales's story remains an example of how individuals with diverse backgrounds impacted the Civil War.

Related Battles

754

90