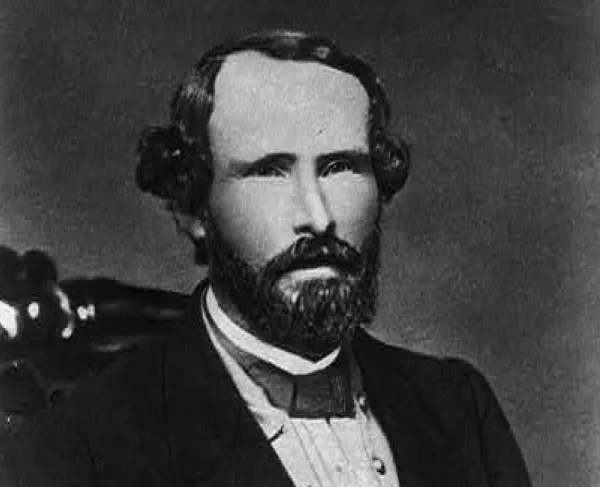

John Newton

“One of the most widely known engineers of the country” according to The Independent.

John Newton is usually remembered for two particular events in his long life. First, he engineered one of the largest explosions prior to the atom bomb to clear New York’s East River’s waterways. Second, he met with President Lincoln during the Civil War, shirking Army protocol, to express his distrust in his superior, Major General Ambrose E. Burnside.

Newton was born August 25, 1822, in Norfolk, Virginia, where the Newton family had lived for nearly two centuries. His father, Thomas Newton, served in Virginia’s House of Delegates and the U.S. House of Representatives. His mother, Margaret Jordan, was Thomas’ second wife. Newton was educated in Norfolk before attending West Point’s Military Academy from 1838 through 1842. He graduated second in his class out of 56, ahead of many peers who would become important military leaders such as John Pope and James Longstreet. Newton remained at West Point in a professional capacity for three more years as an Assistant to the Board of Engineers, Assistant Professor and Principal Assistant Professor of Engineering.

In the next phase of his career in the Army’s Corps of Engineers, Newton was the Assistant Engineer for the construction of Fort Warren in Boston Harbor and Fort Trumbull in New London Harbor. For the building of Fort Wayne in Michigan and Forts Porter, Niagara, and Ontario in New York he was the Superintending Engineer of Construction. Newton’s engineering work expanded along the Atlantic coast from 1853 to 1856 to include surveying breakwaters and rivers, assessing dredges, advising a board on Southern coastal defense site selection and suggesting improvements for lighthouses. He then traveled west as Chief Engineer of the Utah Expedition in 1858; this marked his first time in the field but there was very little action.

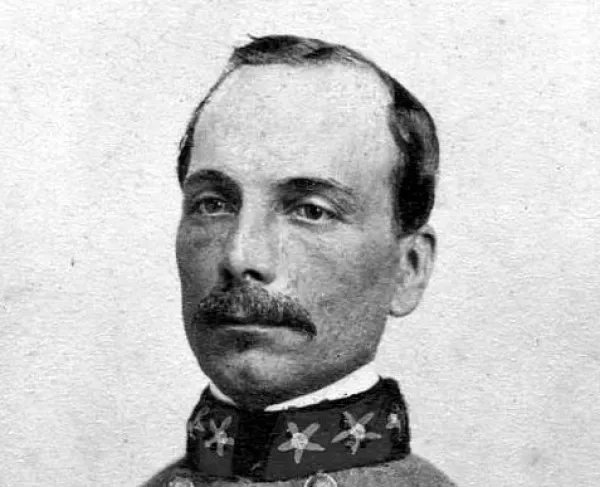

Despite being Virginians, Newton and his brother, Washington, did not resign from the U.S. Army when their home state seceded in April 1861. Newton, at the time, was the Chief Engineer of the Department of Pennsylvania. On June 30, 1861, he fought at the Battle of Falling Waters, his first notable experience in combat. Nearly three months later, Newton was made Brigadier General of Volunteers. During the first winter of war, he received the task of defending Washington, D.C. – managing a brigade and constructing fortifications.

Newton served in the Peninsula and Maryland Campaigns, commanding a brigade under General Henry W. Slocum. Following the Union victory at Antietam, Newton led a division at Fredericksburg. While his division lost fewer men, Fredericksburg was one of the worst defeats for a Union army during the war. Just five days after the disaster, Newton met with President Lincoln to express his concerns about Fredericksburg and the Army of the Potomac’s leader, General Ambrose E. Burnside. Newton stated, “the troops of my division and of the whole army had become entirely dispirited” and had “want of confidence in General Burnside’s military capacity.” Burnside, angered by Newton’s betrayal, presented Lincoln with two options – get rid of Newton or accept Burnside’s resignation; Lincoln accepted the latter.

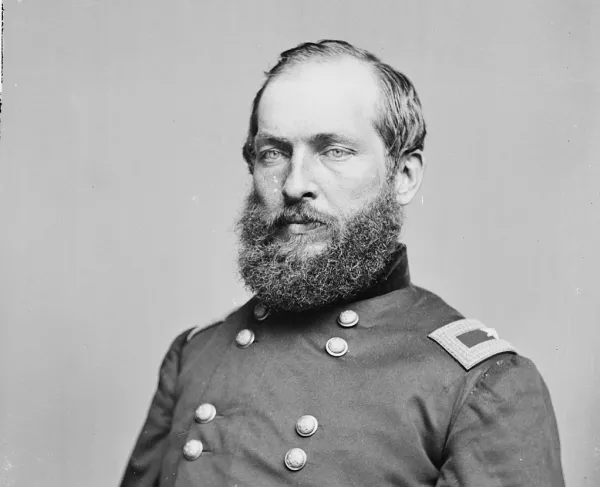

Newton was promoted to the rank of Major General in March 1863. In his new rank, he fought in the Chancellorsville Campaign and at Gettysburg. Following the death of General John F. Reynolds on the first day of battle at Gettysburg, Newton took over command of the First Corps, later leading them while facing Pickett’s Charge. His time as a corps commander ended when his Major General rank was not congressionally confirmed in April 1864. Newton joined the Army of the Cumberland for the Atlanta Campaign under Major General William T. Sherman. There he led a division of the Fourth Corps in at least nine battles, including the Siege of Atlanta.

Newton transferred to Florida in the fall of 1864 to command Department of Key West and the Dry Tortugas. In retaliation to an attack by Confederate troops, Newton planned a joint force expedition to capture Florida’s capital city, Tallahassee, and therefore control the state. The Battle of Natural Bridge on March 5, 1865, ended with disaster. The Union Navy had issues reaching Newport via the St. Marks River, and the army could not drive back Confederate troops over the bridge. In total there were 148 casualties, the battle marked the final Confederate victory of the war and Tallahassee remained as the last Confederate capital east of the Mississippi. Despite this failure, Newton was brevetted Major General in the regular army the following week. He remained in Florida until January 1866.

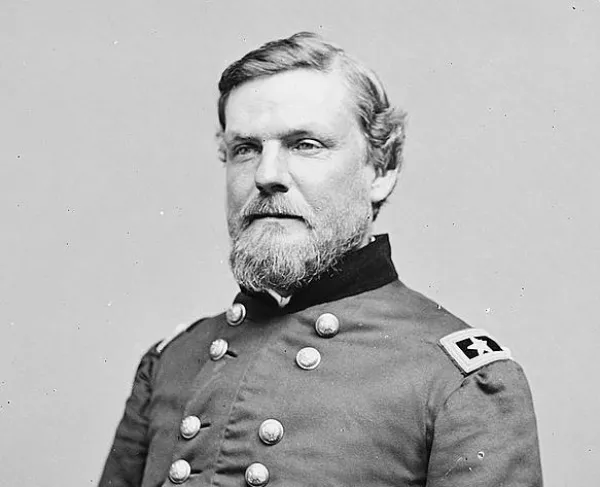

Newton continued in the Army’s Corps of Engineers for twenty years after the Civil War. He was stationed in New York City where he conducted numerous engineering projects. His most significant assignment was clearing the East River’s entrance from Long Island Sound, also known as “Hell Gate.” The passageway posed many dangers to merchant ships with its currents and rocks hidden below the surface. Newton and his team utilized 300,000 pounds of explosives to destroy the obstacles. On October 10, 1885, tens of thousands of spectators turned out to see the explosion. It was recorded that rubble reached over 250 feet into the air and that the shock was felt for miles.

Newton retired from the Army in 1886, but he continued to work as a civilian. For two years he was New York’s Commissioner of Public Works. In 1888, he became the President of the Panama Railroad Company, Panama Steamship Company and the Columbian Steamship Line. He remained in that role until his death.

After enduring months of chronic rheumatism and pneumonia, Newton died on May 1, 1895, at his home in New York City. His wife, Anna Morgan Starr, and several children survived him. The pallbearers at his funeral included colonels and a general, many of whom were engineers and fellow West Point graduates. An American flag draped over his casket, ornamented with a sword, a chapeau and epaulets of a general’s rank. For a short while, Newton was buried at Cavalry Cemetery in Queens, New York before his permanent interment at West Point.