The Whig Party

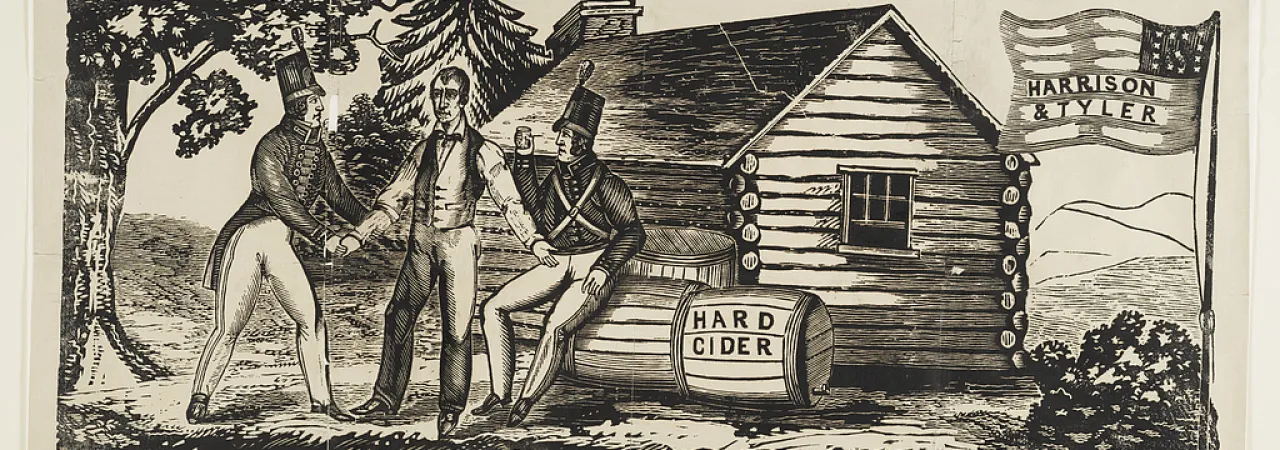

A woodcut created for use on broadsides during the Whigs' 'log cabin and hard cider' campaign of 1840.

Probably no mainstream political party has been as neglected in American history as the Whigs. Active from 1833-1855, the Whig Party shaped antebellum politics but proved unable to overcome tensions over slavery.

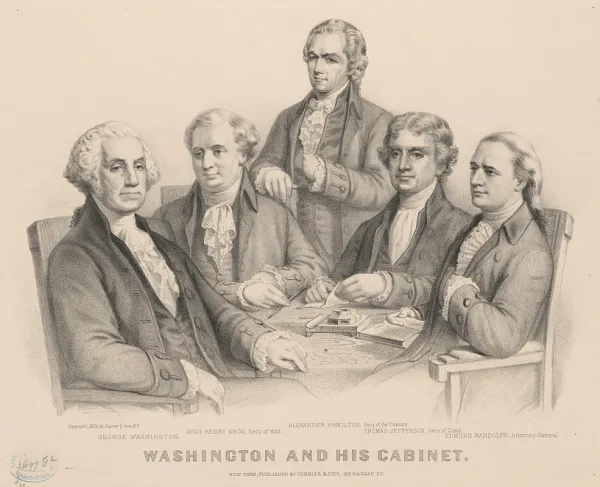

The Whig Party had its origins in the fracturing of the Democratic-Republican Party after the election of 1824. The rivalry between Andrew Jackson, who got a plurality of the vote, and John Quincy Adams, who became the president, split the Democratic-Republicans into two factions: the Jacksonians and the National Republicans. Jackson’s election win over Adams in the following election motivated the National Republicans to coalesce as an opposition. They ran Speaker of the House Henry Clay in the 1832, unfortunately faring poorly against the popular incumbent “Old Hickory.”

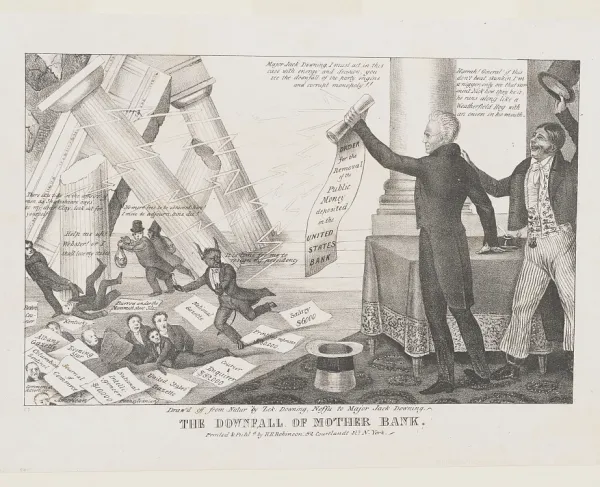

Nevertheless, Jackson’s refusal to recharter the Second Bank of the United States (during what is known as the Bank War) and the nullification crisis over South Carolina’s refusal to recognize the 1828 and 1832 tariffs as law galvanized the National Republicans. Creating a coalition with the Anti-Masonic Party and some anti-Jackson Democrats, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster created the Whig Party in late 1833. The name was picked to invoke the Whigs of the American Revolution’s fight against King George III for their fight against demagogue ‘King Andrew.’

This new party wanted to implement Clay’s economic policy, the American System—a vision for a strong federal government to promote industrial growth and modernization though a national bank, high tariffs, better infrastructure and distribution of federal revenue (from federal land sales) to the states. They opposed a strong Jackson-style executive and, rather ironically, rigid all-encompassing, political parties. Many Whigs were also evangelicals, using their Protestant faith to advocate for public education, voluntary associations, moral restraint and social caution, temperance and anti-Catholic nativism.

While they lost the 1836 election to Jackson’s Democratic successor, Martin Van Buren, the Whigs did find a new star in the process: William Henry Harrison. A war hero for ending Tecumseh's confederacy at the Battle of Tippecanoe and his role in the War of 1812, General Harrison won the party nomination for the 1840 election. Despite being born on a wealthy Virginia plantation to a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the Whigs portrayed Harrison as a frontiersman. Log cabins and hard cider defined the campaign, as Harrison and his Vice President John Tyler comfortably won the White House with 234 of the 294 electoral college votes. This was also the only election the Whigs won a trifecta, controlling the White House and both houses of Congress. “Old Tippecanoe and Tyler too” were supported by an odd coalition primarily of middle-class conservatives, but also New England elites, Southern plantation owners and frontiersmen. They managed to politically unite Massachusetts and Kentucky, no small feat.

Tragically, William Henry Harrison passed away a month after his inauguration, becoming the first president to die in office. His successor, John Tyler, proved troublesome for the Whigs. As a former Democrat, he heavily disagreed with their economic platform, even vetoing Clay’s two bills to reinstate the national bank. In response, his entire cabinet with the exception of Secretary of State Daniel Webster resigned, and in September 1841, he was officially expelled from the Whig Party. House Whigs introduced the first impeachment proceedings in American history against Tyler, and after another veto in 1845, Congress overrode a presidential veto for the first time.

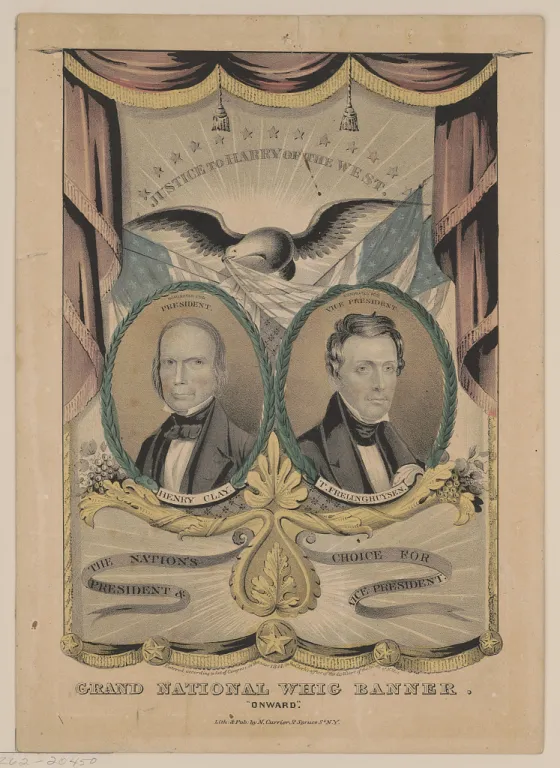

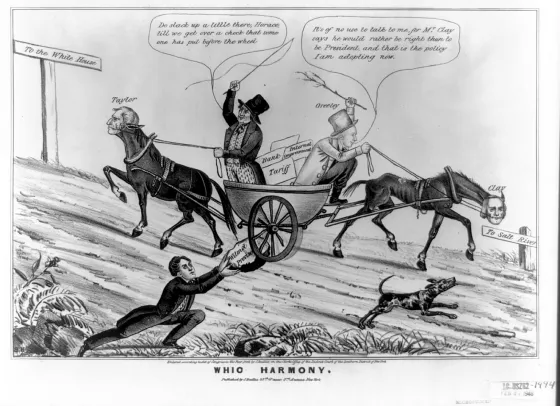

After four excruciating years with Tyler, the Whigs nominated party founder Henry Clay for the 1844 election. Running against Democrat James K. Polk, the election hinged on the issue of Manifest Destiny. While Polk ran on a platform of annexing Texas and Oregon, Clay and the Whigs resisted expansionism, fearing it would reignite tensions over the expansion of slavery. While Polk won, the election was rather close: if Clay had garnered about 5,000 more votes in New York, he would have won the election.

Polk’s reduction of tariffs and restoration of an independent treasury reinvigorated Whigs after their electoral loss. While few Whigs voted against the declaration of war on Mexico in 1846, they remained vocal in their opposition. Many northern Whigs sided with northern Democrats in the House to pass the Wilmot Proviso, a proposal banning slavery in the new Mexican secession, despite its failure in the Senate. As the fight over slavery came back to the foreground, Whigs found themselves divided between the anti-slavery Conscience and the pro-slavery Cotton factions. This internal fracture would only worsen over the coming years.

After the war, the Whigs courted general Zachary Taylor for the 1848 election, hoping to use his fame for a political win. (His service in the Mexican-American War made him the only three-time Congressional Gold Medal recipient in American history). Despite protestations from Clay over Taylor's expansionism being inconsistent with Whig ideologies, Taylor still won the nomination. Many Conscience Whigs already left for the new Free-Soil Party, weakening their influence in the Whigs. As a compromise for the remaining northern Whigs, Taylor chose Millard Fillmore as his vice president. Zachary Taylor won the 1848 election, making him the second elected Whig president.

He was also the second president to die in office, passing away in 1850. As Millard Fillmore became president, the Senate was embroiled in a series of debates on the future of slavery. Henry Clay, the “Great Compromiser,” with the help of Fillmore, brokered the Compromise of 1850 to keep the nation united. Of all the compromise’s provisions, the new Fugitive Slave Act became most consequential for the Whigs. As an ardent enforcer of the act, Fillmore’s reputation rapidly declined in the North, costing him the nomination in the 1852 elections. Instead, after 53 ballots, General Winfield Scott became the Whig nominee. Scott’s loss marked the last time the Whigs ran a presidential ticket.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 exposed all the ugly underlying tensions in the party. Northern Whigs grew increasingly frustrated with the party’s inaction and began defecting. A coalition of Whigs, Free Soilers and anti-Nebraska Democrats created a new party in Michigan and Wisconsin: The Republican Party. William Sward and his Whig faction joined the Republicans the following year. Simultaneously, other Whigs including Millard Fillmore left for the Know Nothings, a party founded on anti-Catholic nativism. By the end of 1855, the Whigs ceased to be a political force, unable to even run a candidate in the 1856 election.

Not all Whigs became Republicans. Many formed smaller regional factions, the most successful of which would become the Constitutional Union Party. This “ghost of the old Whig Party” ran John Bell and Edward Everett in the 1860 election, winning three states in the upper South. Many southern Whigs opposed secession but were outvoted by Democrats. After the Civil War, some former southern Whigs created the Conservative Party, hoping to reunite with their northern counterparts. The attempt failed and the Conservatives merged into the Democratic Party.

The Whig left a lasting impact on the young Republican Party’s ideology. Many Republican leaders, including Thaddeus Stevens, William Seward, Charles Sumner, Charles Francis Adams and even Abraham Lincoln himself, were former Whigs. Interestingly, vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens, was also a Whig. Other prominent Whigs included William Prescott, John Pendelton Kennedy, Horace Greely and Horace Mann.