Compromise of 1850

By the 1840s America was quickly becoming a “house divided.” The issue of slavery and its expansion into the western territories had largely separated political parties and the North and South. Many Americans feared the nation would become so broken that states may secede, after the Nullification Crisis a decade earlier, it was clear, many within the United States felt it their right to secede. Congress faced with the large acquisition of territory from the Mexican American War needed a drastic compromise. The Compromise of 1850 was Henry Clay and later Congress’s solution to the problem. The Compromise sought to end sectional tensions plaguing the country, however, it may have only delayed the inevitable.

When James K. Polk became president in 1845, he set his sights on expanding the United States. The first act of his presidency was approving the offer of annexation sent to Texas by the Tyler Administration. In exchange for becoming a part of the United States, the American government would defend Texas’s southern border fixed at the Rio Grande River, while Mexico claimed that the border lie farther north on the Nueces River. By December 1845, Texas had agreed to the deal, and Polk signed a resolution accepting Texas as the 28th state. As the US and Texas negotiated, Mexico broke diplomatic ties with the United States. Mexico had never federally acknowledged Texas independence and saw this action as an act of war.

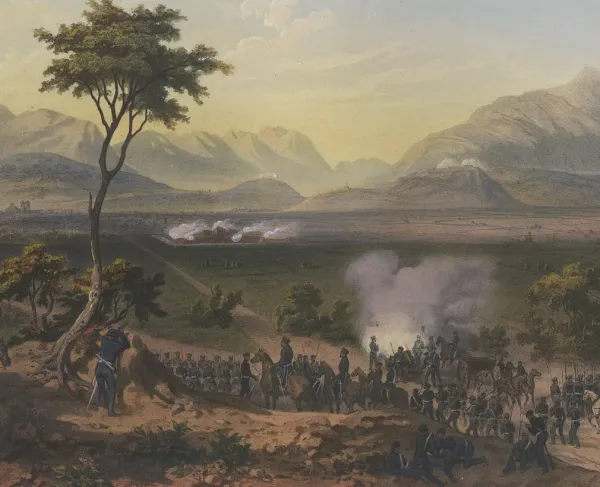

Polk sent troops to the disputed border of Texas and offered a deal to buy the land Mexico claimed in Texas, and additionally in what is now California and New Mexico, from the Mexican government for 25 to 30 million dollars. In the year leading up to the conflict, Mexico’s government was not in a position to negotiate. Mexico had four different presidents in that one year, the final government holding power was nationalistic and claimed Texas was still a part of Mexico’s territory. In April 1846 Mexican soldiers attacked a small number of American soldiers, sparking a war over the disputed border. The Mexican-American War lasted only two years, and concluded with the American army capturing Mexico City. Yet, the war had a long lasting impact on both countries. The United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo concluding the war establishing Texas’s southern border as the Rio Grande and giving America the New Mexico Territory and California for 15 million dollars. The land the US acquired became known as the Mexican Cession. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo radically expanded the United States, and completed the goals of Polk’s Manifest Destiny, while also forcing the nation to confront questions about slavery and self-determination in the new American territory.

Having completed all his campaign promises, Polk did not run for a second term. However, his acquisition of the Mexican Cession created tension his successor would have to calm. Texas was a state committed to slavery and claimed a large portion of New Mexico, which they never truly controlled or governed. Citizens of New Mexico, in contrast to Texas, had long prohibited slavery within the territory. California also required immediate action, after the war military leaders governed the state, and as early as 1848, Americans started to immigrate to California in search of gold. These new citizens voted unanimously in 1849 to outlaw slavery within the territory. Southerners who had supported the expansion of slavery west saw these events as a crossroads for the future of slavery. Additionally, Northern states had recently passed “Liberty Laws” rendering the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 largely ineffective, Southerners began to fear that the Federal Government would soon end the practice of slavery throughout the nation.

Mexican-American War hero Zachary Taylor was elected the new president in 1848. Taylor had been a confusing choice for president. He had been a mostly unpolitical figure before 1848, never voting or even revealing political positions before running for president. He initially did not even declare for a party during the election, until Whig leaders pressured him into committing to the Whigs, in order to gain enough support to be elected president. Because many of his policy positions were nebulous, Americans across parties and borders supported him, impressing their own beliefs onto him. Southerners, knowing Taylor owned slaves, believed he would support the westward expansion of slavery. Whig leaders like Abraham Lincoln and William Seward reminiscent of the only successful Whig presidential candidate, William Henry Harrison, saw a lot of Harrison within Taylor—both were war heroes and famous throughout the country. Division among Democrats also aided Taylor’s campaign. Southern Democrats supported the expansion of slavery, while in the North, many Democrats, led by former president Martin Van Buren, had broken away to create the Free-Soil Party, a stated anti-slavery party. Taylor won the election of 1848 and inherited the new land and the regional tension that came with it.

Taylor’s actual beliefs only stoked sectional tensions. Despite owning slaves, Taylor believed it impractical to expand slavery into New Mexico and California, as the cash crops that slavery cultivated in the South could not be grown in the new territories. Further angering the many Southerners who voted for him, Taylor said he would not veto the Wilmot Proviso, which sought to make all lands west of Texas free territories. Taylor’s solution to the question of slavery in New Mexico and California was simply for them to both become free states immediately, a solution which did not please either side. Taylor ran as a candidate dedicated to saving the Union, but his policy positions pushed the Union further into crisis.

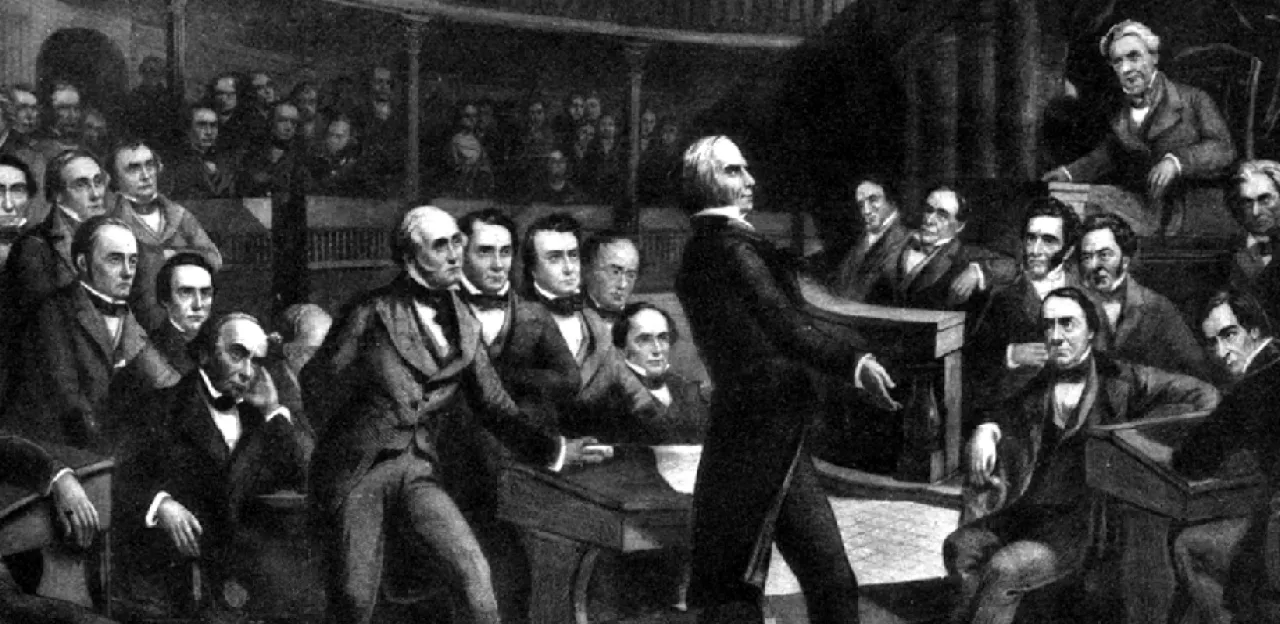

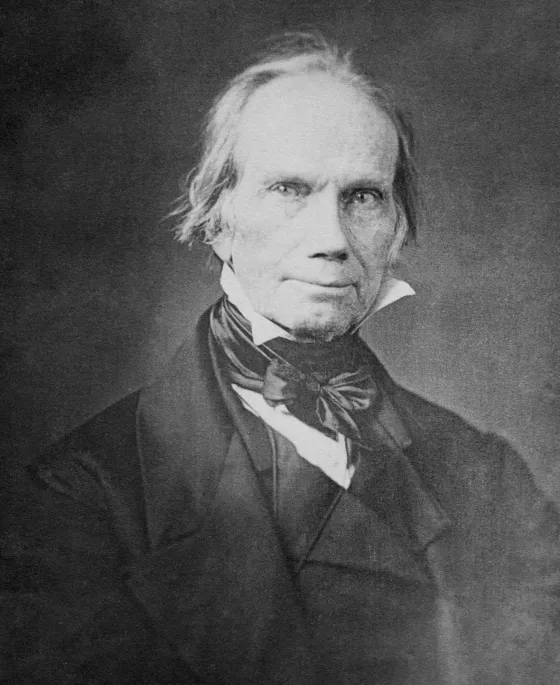

In 1849. Senator Henry Clay dedicated himself to solving the sectional crisis by cultivating compromise between Northern Whigs and Southern Democrats in the Senate. He proposed an omnibus bill which included a multi-part plan to address the sectional tensions. The bill included California entering the Union as a free state, defining Texas’s border in return for debt relief, establishing New Mexico and Utah as official territories, and finally banning the slave trade in the District of Columbia in exchange for a new fugitive slave law. Henry Clay’s proposition was met with radical opposition. John C. Calhoun and other pro-slavery Southerners were angered by introducing California as a free state, while many Whigs saw this as a reasonable compromise allowing slavery to continue. Future Secretary of State William Seward famously gave his “Higher Law” speech in rebuttal saying, “Shall we, who are founding institutions, social and political, for countless millions; shall we, who know by experience the wise and the just, and are free to choose them, and to reject the erroneous and the unjust; shall we establish human bondage, or permit it by our sufferance to be established?”

The compromise, along with the resulting tensions, exploded on the Senate floor on April 17. Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri and Vice President Millard Fillmore engaged in a vicious argument, concluding in a violent interaction: Fillmore scolded Benton that he was out of order, and compromise leader Henry S. Foote of Mississippi drew a pistol on Benton. The tension carried into July as nine slaveholding states sent delegates to Nashville, Tennessee, to discuss a course of action in case the compromise passed. Radicals argued for immediate secession, but moderate Southerners prevailed arguing for compromise with the Whigs. In that same month, Zachary Taylor died of a digestive ailment. As vice-president Millard Fillmore succeeded Taylor. Fillmore had privately expressed support for Clay’s compromise and created optimism among the moderates in Congress. However even with Fillmore’s help, on July 31, the omnibus bill was voted down due to the opposition of northern Whigs and southern Democrats. The next day on the Senate floor, Henry Clay announced he would pass each part of the Bill individually. Yet, the Kentucky Senator was 73 years old and suffering from the tuberculous that would eventually take his life. The disease forced Clay out of the capital for treatment, leaving Stephen A. Douglas in charge of the new compromise.

Fillmore, fearing violence between the Texas militia and Federal soldiers over the west Texas border, took an active role in the compromise. Fillmore denied Texas’s claim to New Mexico and negotiated with both of Texas’s senators. The Senators accepted Clay’s first deal and agreed to new borders with the stipulation that the United States would assume Texan debts. After Texas capitulated, the Senate moved quickly to pass a slightly altered form of Clay’s plan in individual bills. After long debates in the House, the portions were slightly altered and finally put into law.

The final compromise came to be known as the Compromise of 1850 and consisted of five separate bills. The first of these bills created a new, stricter, Fugitive Slave Law. The new law required federal officials in all states, including those in which slavery was prohibited, to help return escaped slaves to their owners. The second law ended the slave trade in D.C. Slavery remained legal in the district but ended the public trading areas near the Executive Mansion (the White House) and Congress, which embarrassed many Northerners. Next, Congress admitted California to the Union as a free state. Penultimately, the New Mexico and Utah territories were officially created and given popular sovereignty to decide the issue of slavery. Finally, Texas’s borders were changed, and the U.S. government took on the weight of their debts.

After the passage of the five bills, Americans across the country celebrated the “compromise that saved the Union.” However, while the deal delayed conflict over slavery and its expansion for ten years, it assisted in pushing the Union into civil war. The Fugitive Slave Law would generate terrible violence upon both free and fugitive black Americans. Any free black person in the United States could be arrested as an escaped slave, as slave hunters only had to declare to a judge that a black person was a fugitive, and they could then be arrested and extradited without a warrant or trial. To many Northerners, the violence of slavery was often abstract; the Fugitive Slave Act brought that violence home to the North.

Along with forcing many Americans to confront the horrors of slavery first-hand, The Fugitive Slave Act also inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin which convinced many Northerners, who may not have seen slavery or its injustice first-hand, to join the abolitionist cause. Though the Fugitive Slave Act was constructed to appease the South, it also expedited the conversion of the North to an abolitionist region, deepening the sectional tensions between the North and South. The Whig party completely broke down during the same decade, being replaced by a party founded by radical abolitionists—the Republican party. The ten-year armistice established by the compromise only pushed the nation further against slavery, making many in the South fear the end of slavery, and many in the North crave the end of slavery, the very issue which would push the South to secede after Abraham Lincoln’s election as president.