When Harriet Beecher Stowe met with President Abraham Lincoln at the White House in 1862, he supposedly greeted her by saying, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war.” Her book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly, published precisely one decade before her meeting with Lincoln fundamentally changed, previously ambivalent, Northerner’s attitudes towards the institution of slavery. The tome proved to be so popular, that the only book that earned greater sales numbers than Uncle Tom’s Cabin during the latter half of the 19th century was the Bible. While her book made many abolitionists, harmful stereotypes proliferated by the work have marred its legacy today.

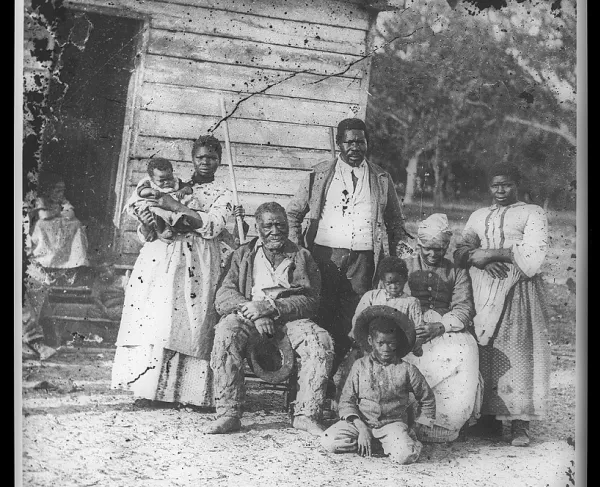

After the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, longtime abolitionist, Harriet Beecher Stowe was inspired to write a novel to persuade Americans against the evils of the institution of slavery. Stowe drew from numerous sources for inspiration. She used the 1849 book The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself as her primary source for her novel, Josiah Henson later became known as “Uncle Tom” and the modern-day “site of Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is actually a cabin near the plantation Henson was a slave. Henson’s slave narrative was not the only inspiration for the work. Stowe also researched the plight of escaped slaves by privately interviewing people she knew had escaped from plantations.

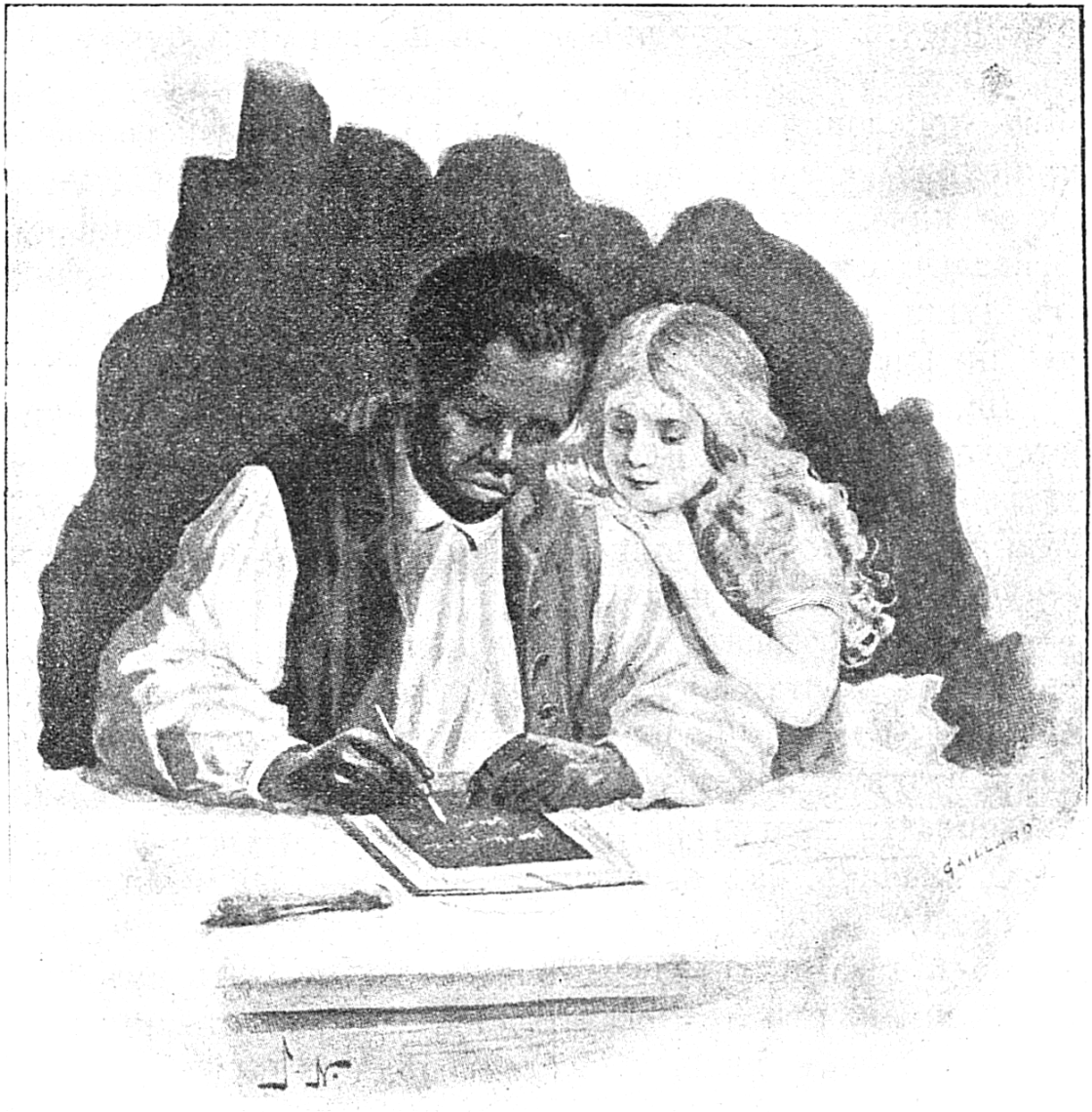

Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a “sentimental novel,” the most popular genre during the mid-eighteenth century, which elicited an emotional response from the reader. Though these works were not usually celebrated critically, they were very popular among the public—especially women, who were leaders in the abolitionist movement. Stowe’s work is dominated by heavy-handed symbolism—every character, character action, and location in work directly symbolize archetypes she had identified within America at the time. It tells the story of Uncle Tom, a good and kind slave. While being transported downriver, Tom saves a pure white girl named Little Eva. To thank Tom for his good deed, Eva’s father purchases Tom. Tom befriends Eva, but she is very sickly. On her death bed Eva begs her father to free his slaves, he makes the promise, but before he can do so, he is killed outside of a café, and the evil Simon Legree becomes Tom’s new owner. Legree demands Tom divulge the location of runaway slaves. Tom refuses, and he is whipped to death. By dying to save others, Stowe makes a direct comparison to Jesus Christ. Many characters are analogous to real-life characters that the author wanted to critique. Miss Ophelia parodies the white moderate; the Senator parodies those who remain complacent to the status quo, Simon Legree is meant to show the brutality of deep south slave owners. While Stowe’s work is not one of subtlety, the characters resonated with Americans.

The book was controversial and largely hated in the South and read widely in the North. The novel was massively influential and became the model for countless protest novels including Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. The book was not nearly as successful after the end of the war; it was not until the Civil Rights movement of the mid-twentieth century that the book was read widely once again. Many Civil Rights leaders critiqued the novel for reinforcing hateful stereotypes. Stowe depicts slaves who embody popular stereotypes of black Americans in the mid-nineteenth century including the “happy darky,” “the tragic mulatto,” “mammy,” and most famously, it constructed the stereotype of the “Uncle Tom.” While Stowe intended Tom to be Christlike, forgiving those who condemned him to death, many read his character as a slave who bowed down and gave in to the white slaveowner. This stereotype was expanded by post-war minstrel shows which replaced the death of Tom with Tom reconciling with his oppressors. Stowe never licensed any version of her book to be shown dramatically; as a result, directors took liberties with the work and many shows fundamentally changed the plot and characters. Over three million Americas saw what became known as “Tom Shows.” In comparison, more than ten times as many Americas saw Tom Shows than read the book.

While the passage of time has complicated the legacy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the book no doubt was a significant factor in the North’s realignment from moderate to abolitionist. Modern black literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. argued that despite its apparent faults, “[Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a] central document in American race relations and a significant moral and political exploration of the character of those relations.”