"'Oklahoma Cotton Field' Overseer and Negro cotton pickers, ca. 1897-1898"

Contemporary portrayals of the United States' Westward Expansion often painted the process as the inevitable march of progress. Sadly, many of the complications surrounding expansion proved to be milestones on the path to the American Civil War. As the borders moved westward, so did American settlers, which raised several serious questions over what certain Americans were bringing with them; particularly the slaves. Historians have often noted how the complications surrounding the acquisition of new territory exacerbated domestic sectional tensions within the country around several major economic and social issues, since both North and South saw the west as the place to guarantee their distinct and ultimately conflicting visions for the country. Despite multiple compromises to work around these issues, conflict inevitably came to a head as Southerners dug their heels in to defend the institution upon which they built their society from hindrance.

Though the majority of Americans were involved in agriculture production of some form throughout the 19th century, the southern economy was uniquely specialized in the business. Southern agriculture itself also differed from that of the North as it was built mostly on specific cash crops like cotton, tobacco, sugar and rice instead of food production. Those first three crops were extremely labor intensive, and so the use of unpaid, forced labor helped make their production far more profitable than it otherwise would have been. A little less than half of white southerners owned slaves, and only a small percentage of slave owners themselves ran the enormous plantations where these crops were grown, but since they, especially cotton, was in such high demand in the North and Europe, these men and their families became fabulously wealthy, enough to completely dominate Southern social and political life, as well as the representation of Southern states in Washington. The racialized aspect of slavery also gave poorer whites enough incentive to support slavery as well, as even the poorest white man possessed more dignity than any slave. And as the Northern economy began turning away from farms and towards factories, the South, outside of a few large cities, further entrenched itself in these specialized exports as well as the system of chattel slavery that supported it. But that entrenchment presented a problem for Southern elites, as it did not leave much room for the same kind of dynamic economic growth as the North was experiencing through industrialization. The South was convinced that the survival of their economic system, which intersected with almost every aspect of Southern life, lay exclusively in the ability to create new plantations in the western territories, which meant that slavery had to be kept safe in those same territories, especially as Southerners increasingly saw more and more hostility towards the practice.

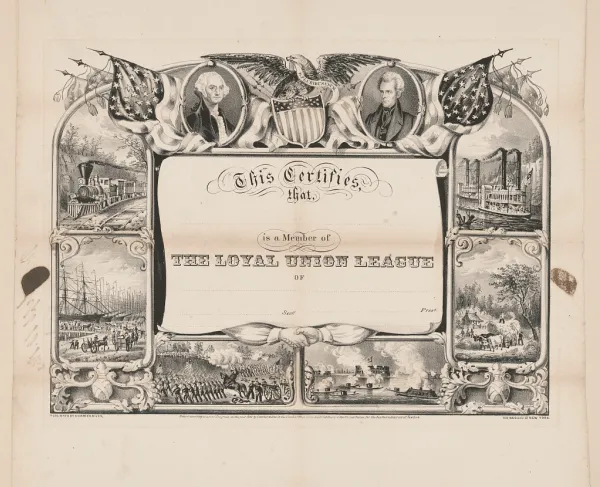

Was the South right to view the North as conspiring against them to destroy slavery? They certainly felt that way in 1860 after the election of Abraham Lincoln and John Brown's 1859 “Raid” on Harper's Ferry, and the Abolitionist movement had been steadily growing in America since its first appearance in the early 19th century, but were they right in labelling all Northerners as such? Many Northern figures did have an entirely separate vision for the new territories. As Northern states and cities became more crowded, many sought refuge in the west away from the urban clamor, but because they planned to practice the same kind of agriculture practiced elsewhere the north, typically subsistence farming by small, independent (or yeoman) planters, they dreaded the thought of competing with cotton farming and slave labor over land and resources. The desire to protect these settlers from such overwhelming competition formed the basis of the Free Labor movement, which sought to restrict slavery from the new territories as much as possible. It should be said of course, that this movement existed for the potential benefit of white Americans and white immigrants from Europe seeking a new life in the west, although many in the Labor movement did deem slavery to be morally wrong on its own. A vocal percentage of that group went on to join the growing Abolitionist movement that wanted to end slavery for good, but at no point did they form the majority of slavery's opponents.

It is worth noting that many Northerners had their own conspiracy theories about the reach of Southern domination of American society. It was true that the Three-Fifths clause in the Constitution that allowed Southern states to partially count the enslaved population in awarding additional congressmen and electors gave the South disproportionate influence on Washington, especially since they basically represented the interests of a small number of landed elites, but not to the point where they controlled the entire federal government. The situation did allow Southern politicians to vote in unison as a block for slavery interests, aided by sympathetic Northerners.

Faced with such a startling divide on the issue, policy makers in Washington decided to form a compromise, or an agreement that sought to address certain concerns on both sides. This first attempt to bridge the gap between North and South took the form of the Missouri Compromise of 1820. To ease tensions, Congress decided that the territory of Missouri would enter the Union as a slave state, while the territory north of New Hampshire would enter as the free state of Maine. This would allow slave states to hold parity with free states in the senate, which held two members from each state and would act as a check to Northern domination of the House of Representatives, where the number of members from each state was proportional to population. Congress also planned from then on to allow new states from the west to enter the Union as pairs, one slave and one free, to maintain parity in the Senate. When President Monroe passed the Compromise into law, many congratulated themselves on successfully navigating the issue, as at that point even most slave owners believed the practice would die a natural death eventually, but a prominent few mourned the chance to deal with the issue decisively. Former President Thomas Jefferson, whose views on slavery could fill its own book, compared the treatment of slavery to holding a wolf by the ears, writing, "we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go."

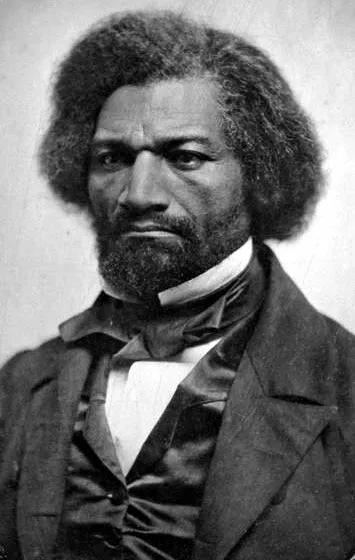

For a few years, the Compromise held firm, but starting in the 1830's, regional tensions again put pressure on expansion. 1831 in particular saw the South become ever more defensive and willing to justify slavery thanks to Nat Turner's rebellion, this time as a moral good instead of a necessary evil. The Nullification Crisis, during which South Carolina tried to block federal tariffs designed to foster industrial growth in the North, also convinced many Southerners that Northerners planned to use the power of the federal government to cripple the Southern economy. More stress on the deal arose as more territories were added. The Texas Revolution, started in part by Anglo-American settlers seeking to preserve slavery after Mexico had abolished it, and its subsequent annexation by the U.S. as a state led to a flurry of criticism by Northerners against those they saw as putting the interests of slavery over those of the country as a whole. Those criticisms got only louder as the Annexation led to a war with Mexico, and talk among certain politicians became not whether the U.S. should take even more territory from its defeated rival, but how much. Then-congressman Abraham Lincoln in particular challenged President James K. Polk to prove his assertion that the war began when Mexican troops skirmished with American patrols on American soil. Abolitionists like the ex-slave Frederick Douglass accused war supporters in Congress of openly conspiring to annex far more territory than the conflict necessitated; not a particularly unfair claim as talks of annexing territories like California existed in Democratic circles before the war itself, and during treaty negotiations, Southern senators like Jefferson Davis pushed much more forcefully for taking more land beyond Alta California and Nuevo Mexico. Davis himself introduced an amendment to add the majority of Northwest Mexico to the Cessation, while some supported conquering the entire country itself. This “All of Mexico Movement” failed rapidly for a number of reasons, particularly the challenge of placing the entire country under military occupation and fears of granting conquered Mexicans citizenship status, the idea remained a favorite among a few prominent Southerners. During the 1850's, the secret society Knights of the Golden Circle dreamed of eventually expanding through Mexico and into Central and South America, as well as control of the entire Caribbean Archipelago. In the words of popular Charleston secessionist Robert B. Rhett, "We will expand, as our growth and civilization shall demand – over Mexico – over the isles of the sea – over the far-off Southern tropics – until we shall establish a great Confederation of Republics – the greatest, freest and most useful the world has ever seen." On the other side of the isle, Wilmot's Proviso, a bill proposed by Pennsylvanian Congressman David Wilmot, sought to restrict slavery from any territory taken by Mexico. To Southerners’ shock and horror, the bill actually managed to pass the House, before rejection by the Senate.

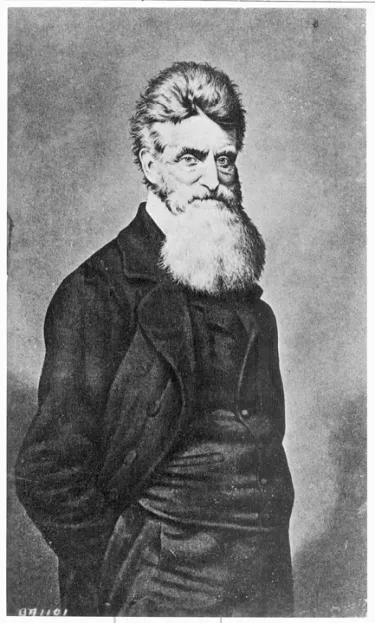

By now this North/South rivalry had been rapidly mounting, but things truly came to a head in 1850 with the reorganization of the California territory. Flooded with settlers seeking their fortunes from the Gold Rush, California finally felt itself ready to enter the Union, but desired only to do so as a free state. This caused enormous consternation in Congress, as such a move would upset the careful North/South parity in the Senate. To rectify the issue, Congress produced a series of bills collectively called the Compromise of 1850, allowing California into the Union as a free state as well as banning the domestic slave trade in the District of Columbia. Meanwhile, Congress allowed the Utah and Nebraska Territories to decide for themselves whether or not to restrict slavery within their borders, a concept developed by Illinois Democrat Stephen Douglas called "Popular Sovereignty." To appease slave-owners, Congress agreed to put away the Wilmot Proviso for good, decided upon the official borders for Texas, and most controversially, passed a new Fugitive Slave Act. The new act punished any citizen who did not aid in arresting an escaped slave, while also lessening the standard of evidence slave owners needed to declare someone to be their own runaway property. The latter provision helped lead to the kidnapping of free black men and women, who now could not argue their case in court, but an even greater effect was that white Northerners previously indifferent to slavery were now forced to at least confront the issue, and many responded by accusing the South of undermining their own state laws. Far from saving the Union, as Stephen Douglas believed, the Compromise merely brought the cause of division to the forefront of every mind in America, and it showed four years later with the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Still believing that Popular Sovereignty provided an effective way to heal tensions. Stephen Douglas led the Senate to pass a law allowing the newly-formed Kansas and Nebraska Territories choose whether or not to ban slavery, placing both Northerners and Southerners on edge over the eventual result, causing a good number of pro-slavery Missourians to move into Kansas and attempt to sway the locals through force. Abolitionists and Free Soilers responded by moving in as well and attacking pro-slavery activists, setting off a border war between settlers. Kansas ultimately did enter the Union as a Free State, but not without the deaths of over 100 people, guerillas and civilians alike.

Though the various compromises made over slavery and the western territories helped keep the Union together longer for decades, they ultimately failed to deal with the root of the issue decisively. And the further undermining of the agreements did not stop there. Violence continued in Kansas, and in 1857, the Supreme Court issued the infamous Dred Scott Decision, which declared that Congress never had the authority to restrict slavery in the territories to begin with. But despite that enormous Southern victory, the election of Abraham Lincoln, the first president from the anti-slavery Republican Party, was too much for the Southern States to bear, and so the process of secession began.

Further Reading:

- Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America: Ira Berlin

- American Slavery: 1619-1877: Peter Kolchin

- Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era: James M. McPherson

- Slavery: A World History: Milton Meltzer

- The Slaves Cause: A History of Abolition: Manisha Sinha