While only a short episode in American politics, the Wilmot Proviso provides insight into anti-slavery positions among northerners and reopened debates about slavery in the territories which had lasting effects on the larger American political landscape.

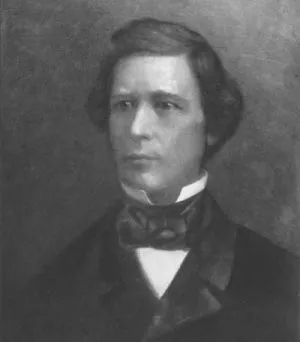

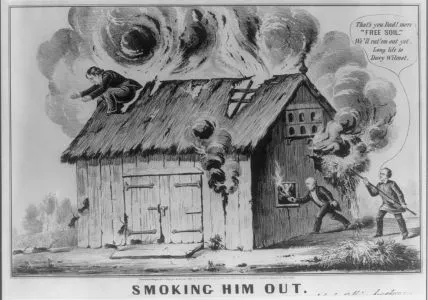

On Saturday, August 8, 1846, amidst the Mexican-American War, President James Polk proposed an appropriation bill that would allocate $2 million to purchase any potential territory from Mexico as war reparations. It was a poorly kept secret that Polk engaged in war with Mexico to gain territory, but this served as the first time that the president publicly acknowledged his intentions. Prior to Polk’s introduction of this bill, Congress voted to adjourn their session on Monday, August 10. Polk introduced the bill at the eleventh hour in an attempt to get it quickly passed without any riders. However, Democratic Representative David Wilmot of Pennsylvania quickly foiled the commander in chief's plan. During his ten minutes allotted time to speak on the bill, Wilmot dropped a bombshell. He proposed as an amendment to Polk’s appropriation “that, as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico…neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory, except for crime, whereof the party shall first be duly convicted.” This provision that slavery be excluded from the Mexican Cession became known as the Wilmot Proviso. Wilmot’s intentions for proposing his proviso aligned perfectly with the intentions of the free-soil movement. Wilmot did not act alone in his proviso. Many northern Democrats remained angry over the party’s treatment of Martin Van Buren, by throwing him over in favor of James Polk for the presidential nomination and replacing Van Buren with Polk as Andrew Jackson’s true successor. In addition to their anger over Van Buren, many northern Democrats were upset over the perceived subjugation of northern interests to southern ones and as such wanted to lash out against Polk and the slave power. Additionally, they wanted the potential territory gained from Mexico to be exclusively reserved for whites for political and economic reasons.

In an essential Hail Mary play, Representative William Wick (Democrat-Indiana) tried to supplement Wilmot’s amendment with one that extended the Missouri Compromise line to this potential territory but that attempt failed. In the House, Wilmot’s amendment passed by a vote of 84-64, every negative vote except three came from a slave state. Polk’s appropriation bill was amended, and a second vote was held with an 85-80 outcome. Similar to the previous vote, this vote was also along sectional lines. This represents a shift in antebellum politics as previously bills were voted almost exclusively along party lines, and this was the first bill since the Missouri Compromise that was voted on along sectional lines. This vote also illustrates that southerners would rather prevent territorial expansion altogether than have expansion without the extension of slavery. This southern opposition combined with the Wilmot Proviso highlights that Americans directly linked territorial expansion with the prevention or the expansion of slavery.

After the House vote, the bill moved along to the Senate on August 10; however, by accident, the Senate never voted on the bill. In a scheme to force a vote without any amendments that would repeal the Wilmot Proviso, Senator John David (Whig-Massachusetts) planned to filibuster the bill until eight minutes before the session expired, intending to vote on the bill then. However, he was interrupted in his speech and notified that the Senate clock was eight minutes faster than the clock in the House’s chambers. Consequently, the House of Representatives adjourned which triggered the expiration of the Congressional session without a Senate vote on Polk’s bill. This meant that Polk’s appropriations bill also expired along with the Wilmot Proviso. When Congress began its next session, Wilmot re-proposed his proviso, but Polk’s new appropriation bill passed without Wilmot’s rider. Despite the drama over the Wilmot Proviso only lasting three days, this event signifies a shift in American politics to one that is based on sectional lines over party lines and exemplifies an important position among anti-slavery northerners.

During the Antebellum period, even though they did not own slaves or directly benefited from the institution, many northern Democrats supported measures that protected and maintained slavery as part of a coalition with southern Democrats. As southern influence was known as the slave power, Northerners often referred to this coalition as part of the “Slave Power Conspiracy.” However, by August 1846, Wilmot did not want to bend to the will of the slave power anymore and advocated for anti-slavery positions, which included his proviso. In the 1840s there was a large variety of positions within the anti-slavery movement. At one end of the spectrum was the colonization movement which advocated for gradual manumission of slaves followed by emigration to “liberated” colonies, often in the Caribbean or Africa. Many prominent antebellum politicians supported colonization and joined colonization societies, including Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln. As Lincoln stated the prevailing view behind colonization was that “it [was] better for [blacks and whites] to be separated” and thus slaves should no longer live in the United States following their emancipation. Abolitionists represented the other end of the anti-slavery spectrum, who desired immediate and forced abolition without any compensation for slaveowners. Abolitionists were few and far between in the 1840s as many Americans considered them too radical.

Free-soilers fell somewhere in the middle of the anti-slavery spectrum, which included Wilmot and a variety of northern politicians. At the heart of the free-soil movement was the commitment to keep slavery out of newly gained territories. Unlike abolitionists, free-soilers did not want to touch slavery in places it currently existed but rather wanted to stop its spread. Free-soilers objected to slavery not because they viewed it as an abominable institution, but because it hurt northern whites. Some politicians felt that the slave power disproportionally dominated national politics thereby limiting northern political influence.

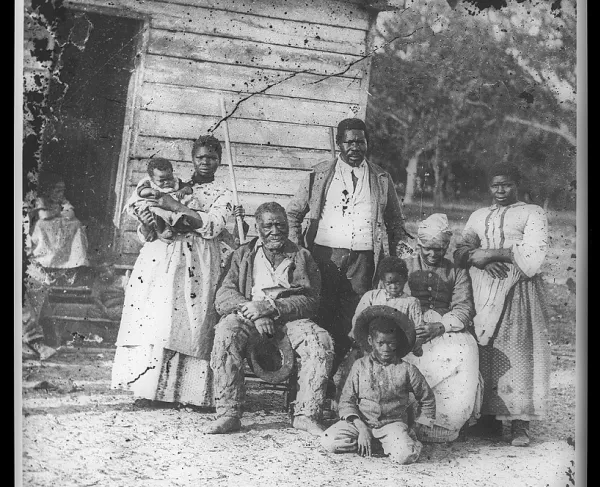

Additionally, slavery created an aristocratic planter class that northerners viewed as incompatible with American democracy. Finally, slavery restricted white economic mobility by eliminating competition for labor in the areas it existed. Restricting slavery in the territories opened those lands to free white laborers and promoted labor competition, which benefitted the North. Wilmot and other free-soilers made it clear that the free-soil movement was entirely for the benefit of white northerners with little concern for those held in bondage. Free-soilers made up an overwhelming majority of those in the anti-slavery movement which illustrates that the movement was born out of hostility to perceived southern political domination and the desire to promote northern white interests rather than an actual humanitarian concern for slaves.

While the Wilmot Proviso occurred so suddenly and swiftly it had a lasting impact on American politics. The proviso provides insight into the anti-slavery movement in antebellum America. Not only did it begin to realign the structure of American politics, with votes in the House and Senate, votes and political leanings became increasingly based on sectional lines as opposed to party lines; it also reopened the debate over slavery in the territories and slavery in general—a debate that prolonged up until the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Further Reading: