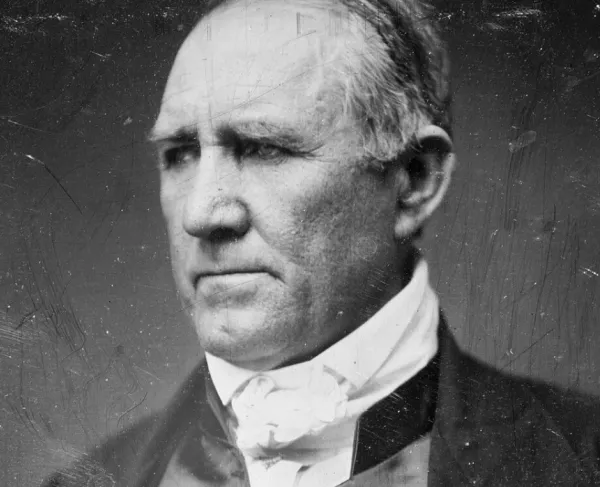

Daniel Webster

One part of the so-called “Great Triumvirate” that dominated American politics in the first half of the 19th century, Daniel Webster was born in on the New Hampshire frontier on January 18, 1782. His father, a veteran of the American Revolution, was a farmer and tavernkeeper. As a boy, Webster was small and frail, who often entertained tavern guests with readings and recitations, the first hint of a man who would become one of America’s most famous orators. Webster entered Dartmouth College at age 15, where he excelled at public speaking.

By 1807, he had established himself as a distinguished lawyer in Portsmouth, NH, representing the interests of the city’s shipowners and merchants. He married Grace Fletcher, a minister’s daughter, in 1808, and had five children with her. He strongly opposed President Thomas Jefferson’s embargo, which disproportionately hurt New England commerce, and once the War of 1812 broke out, he also became a vocal opponent of the war. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives as a Federalist, where he spent much time opposing “Mr. Madison’s War,” conscription, and defending states’ rights. He was re-elected in 1814 and 1815, after which he moved to Boston, Massachusetts.

In Boston, Webster represented prominent businessmen in court and quickly became one of the highest-paid lawyers in the country. He argued several of the landmark cases in the early history of the Supreme Court that expanded federal authority, including Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). At the same time, Webster was gaining fame as an orator. His physical appearance intensified his speeches, with a dark complexion and glowing, penetrating eyes. He was again elected to the House, serving from 1823 to 1827, this time as a representative from Massachusetts. He then traded his House seat for a seat in the elite Senate in 1828, again representing Massachusetts. Grace, suffering from cancer, passed away on their journey to Washington. Two years later, Webster married Caroline LeRoy of New York, although rumors in the District continuously swirled about his alleged infidelity.

Although he had previously opposed tariffs on foreign imports, Webster voted for the Tariff of 1828, also known as the Tariff of Abominations. This tariff set off the Nullification Crisis, in which South Carolinians, led by Vice President John C. Calhoun, another member of the "Great Triumvirate," championed states’ rights in the face of an overreaching federal government and threatened to secede. Webster defended his ideological enemy President Andrew Jackson and the power of the federal government. His speech in reply to Senator Robert Hayne of South Carolina is known as one of the greatest speeches given in Congress, in which Webster championed the federal government, saying that “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.” This stalwart defense made him a hero of proponents of a strong federal government, especially once the crisis passed when South Carolina backed down and the Union remained.

After allying with him during the Nullification Crisis, Webster bitterly clashed with Jackson over the Second Bank of the United States, which Jackson had set out to destroy, believing it to be undemocratic and unconstitutional. Webster became the bank’s champion, but his resistance proved futile when the bank’s charter expired in 1836. The emergence of the Whig Party as a counter to the Jacksonian Democrats gave Webster a new party, and he unsuccessfully ran for president on the Whig platform the same year.

In 1841, Webster was appointed Secretary of State under Whig President William Henry Harrison. When Harrison died weeks into his term, Webster was forced to serve under John Tyler. The rest of the Cabinet, prompted by Henry Clay, the third man of the "Great Triumvirate," resigned in protest, but Webster remained on. In Tyler’s administration, Webster achieved multiple foreign policy successes, most notable the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842. The treaty established the border of Maine, created long-lasting peace with Great Britain, suppressed the global slave trade, and the treaty’s extradition clause became a model for later foreign ministers. However, after financial difficulties and a disagreement with Tyler over the annexation of Texas, Webster resigned from the cabinet in 1843.

To supplement his income, Bostonian businessmen raised money to get him back to the Senate. He strongly condemned President James K. Polk’s war with Mexico, demanding it be brought to an end and opposing any acquisition of territory. In an act of cruel irony, one of Webster’s sons died of typhoid fever while serving in the war.

In 1850, when acquisition of territory from Mexico nearly tore apart the Union, Webster supported Clay’s Compromise of 1850, believing preservation of the Union to be of the utmost importance. He argued that a ban on slavery was unnecessary because of the climate of the Southwest, which was inhospitable to large-scale plantation agriculture. In his “Seventh of March” speech, he spoke to Congress “not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American.” This infuriated antislavery Whigs and doomed whatever presidential aspirations he had left.

But his political career was not yet over. He once again served as Secretary of State, this time under President Millard Fillmore. He gained more animus from antislavery Whigs when he enforced the Fugitive Slave Act (part of the Compromise of 1850). He attempted to run for president on the Whig platform in 1851 but lost the nomination to war hero Winfield Scott. Some discontented Whigs and third parties would vote for Webster, though he never officially endorsed his own candidacy.

His poor health made it difficult to continue to serve, so in autumn 1852, he returned to Marshfield, his estate that he often used as a refuge from political frustration, where he died on October 24. Only one of his five children outlived him, Daniel Fletcher Webster, only to be killed a decade later at the Second Battle of Bull Run, wearing the uniform of the country his father had sought desperately to preserve, at the head of a regiment (the 12th Massachusetts) that was nicknamed the Webster Regiment.