A Brief Overview of the Mexican-American War 1846-1848

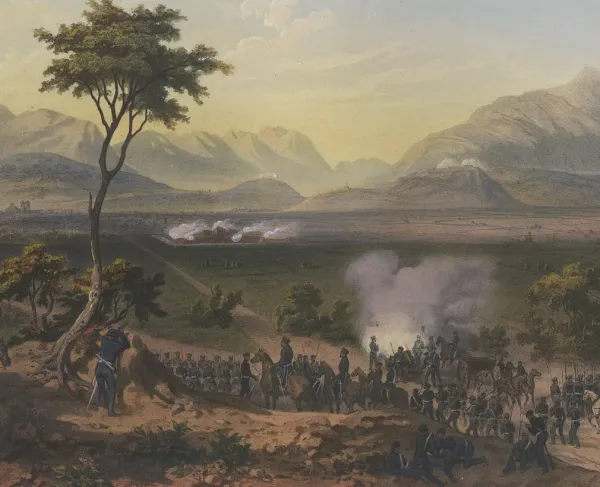

Two long years had passed after the initial shots were fired, sparking the Mexican American War in 1846. After United States forces under General Winfield Scott captured and occupied Mexico City in 1848, Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna surrendered. Thus, ending the war which began as a border dispute.

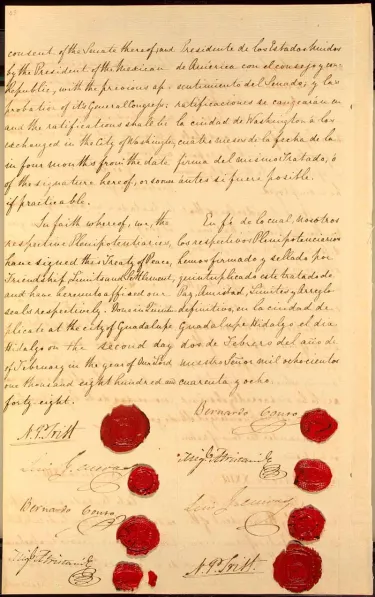

The peace treaty between the two nations was deliberated and signed in the town of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, located in Mexico City today. The treaty sought to end the war with the peaceful transfer of disputed lands and the formal recognition of the United States’ annexation of Texas by the Mexican government. The recognition of Texas as American soil was crucial to the treaty deliberation as the war began over the military presence of Mexican forces within the Texas region. As such, the American people believed that the Mexican army was attempting to retake Texas after the state’s successful revolution against Mexico.

However, despite Mexican President Santa Anna having signed a treaty with the Republic of Texas, the federal government of Mexico refused to acknowledge the treaty as valid and still considered Texas a state in the Mexican Republic. The subsequent pleas for annexation by the Texans to the United States prompted fears of sparking war, which it inevitably did. Furthermore, the proliferation of slavery in Texas worried abolitionists who feared that the annexation of Texas was going to upset the balance of “Free” and “Slave” states set forth in the Missouri Compromise. As a result, Whigs and the northern American population were opposed to war with Mexico while the southern slave states advocated for annexation and even war.

Initially, United States President James Polk wanted to first purchase land from Mexico that later became parts of California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Oklahoma. Additionally, Polk hoped to also establish the Texan border along the Rio Grande. However, the Mexican government rejected this offer. As a result, President Polk ordered American General Zachary Taylor to establish a military camp beyond the Nueces River, which was considered by the Mexican government as the southern-most border of Texas. When the Mexican military finally attacked Taylor’s army, war was declared, and Polk forced westward expansion through conflict with Mexico.

Even though the war was opposed by many Americans, Americans rushed to volunteer and fight. As a result, many soldiers of the United States Army and later Confederate Army gained combat experience, in part due to their practical experience in the Mexican American War. Furthermore, many military officers that had graduated West Point fought side-by-side with their future adversaries during the war in Mexico.

After two years of fighting, Mexico finally capitulated. The Mexican government sought to make peace with the United States who still wished to purchase the land outlined before the war began. Although, this time, the asking price for the land was considerably less than before. At almost $15 million, the price for the land known as the “Mexican Cession” almost decreased by 50%. Additionally, the treaty stipulated that the Rio Grande was to be the southern-most border between the United States and Mexico. However, once the treaty arrived at the United States Senate for ratification, Jefferson Davis and other Southern Democrats began advocating for further territorial expansion into Mexico across the Rio Grande. Nevertheless, the small contingent of expansionist Southern Democrats was overruled by the rest of the Senators who made minor changes to the treaty before ratifying it. Ultimately, the treaty brokered by Nicholas Trist was ratified in the United States Senate 38-14 on March 10, 1848, with the treaty becoming effective May 30, 1848.

While the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo did not end the purchase of land between the United States and Mexico, it solidified the American ideals of Manifest Destiny. Once the treaty was effective, the United States of America and its people had the ability to migrate and live on both coasts of the continent. Thus, formalizing the American ability to live and prosper “from sea to shining sea."

Further Reading

- So Far From God: the U.S. War with Mexico 1846-1848 By: John S. D. Eisenhower

- A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico By: Amy S. Greenberg

- The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery Expansion and the Coming of the Civil War By: Michael F. Holt

- The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War 1848-1861 By: David M. Potter