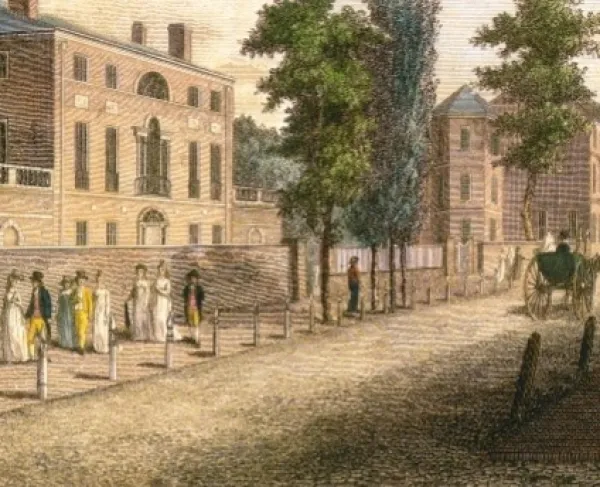

Founded in June 1780, The Ladies Association of Philadelphia was the first women-only association in the colonies and “embodied greater organizational and economic power than any previous organization of women in American history.”[1] The driving force behind The Ladies Association of Philadelphia was Esther DeBerdt Reed (1746-1780). Although English by birth, she was deeply affected by her adopted nation's drive for independence and its desire for freedom. As the wife of Joseph Reed, who served as George Washington’s secretary and later as the President of the Supreme Executive Council, she was concerned with public affairs and familiar with the causes of the Revolutionary War as well as the difficulties faced by soldiers and citizens who supported it. In June 1780, she published “The Sentiments of an American Woman” to mobilize women's support for the war. This broadsheet called for women to make personal sacrifices to support the Continental Army. Reed’s formation of the Ladies Association of Philadelphia was the first women-only association in the colonies. Her media campaign and political organization allowed her message to reach a national audience and raise significant sums for the Continental Army. However, the most lasting legacy of her actions was to provide a template for how women could exercise more influence in the public sphere and prove that women-led organizations could be successful.

At the beginning of 1780, the Revolutionary War had lasted five years, creating significant economic strain for the new country by creating supply shortages and rampant inflation. These financial troubles impacted the Continental Army, which saw shortages in food, clothing, and ammunition, which made George Washington’s efforts to continue the war increasingly difficult. George Washington wrote to Joseph Reed, whose role as the President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania was equivalent to a modern-day governor, on May 28, 1780, imploring him for more support from Pennsylvania. “Nothing could be more necessary than the aid given by your State towards supplying us with provision.” However, Joseph Reed’s political enemies, The Republican Society, resisted his efforts to raise more funds for the Continental Army, ensuring he would bear the blame for Pennsylvania's inability to supply more funds[2]. Consequently, on June 10, likely inspired by Washington’s latest letter to her husband, Esther DeBerdt Reed and other prominent women in Philadelphia, including Sarah Franklin Bache (daughter of Benjamin Franklin), organized The Ladies Association of Philadelphia to solicit funds for the Continental Army and published Reed’s broadsheet “The Sentiments of an American Woman.”

While the paper inspired action by pointing to historical examples of patriotic women, Reed’s eleven-step plan provided an organizing framework for any group of patriotic women to follow. For example, she instructed appointing a "Treasuress” who would collect and register the sums and decide how George Washington could spend the funds. Reed also capitalized on the growing newspaper industry in the thirteen colonies to convey her message. On June 13, the Pennsylvania Packet discussed the Ladies of Philadelphia's fundraising plans. On June 21, just days after its release, the Pennsylvania Gazette published Reed's entire paper. Newspapers in other states then spread stories of women’s support for the Revolutionary cause. "The Ladies of Trenton" announced they were "emulating the noble example of their Patriotic Sisters of Pennsylvania." An anonymous letter published in the Maryland Gazette describes how women signed up for fundraising. "Those in the country returned immediately to the city to fulfill their duty.” Newspapers helped spread awareness among women, encouraging them to actively contribute to the war effort, creating a ripple effect of support and driving political engagement. Dr. Benjamin Rush, husband to Julia Rush (one of the founding members of the Ladies Association), noticed a significant change in his wife. He wrote to John Adams about Julia, “who you know in the beginning of the war had all the timidity of her sex as to the issue of the war...distinguished herself by her zeal and address and is now so thoroughly enlisted in the cause of her country that she reproaches me.”

Not everyone in the colonies supported these efforts. For example, Anna Rawle, a Tory, harshly criticized Reed's activities in her letters. She was particularly shocked by women fundraising, writing that the "absurdities" of "the Ladies going about for money exceeded everything." However, the more common sentiment expressed was that of Sarah Jay, wife of founding father John Jay, who wrote about the Ladies, “I am prouder than ever of my charming countrywomen.”

The Ladies Association of Philadelphia, of which Reed was the first president, became the first female voluntary association in the United States. The public nature of The Ladies’ activities was critical for the success of their fundraising efforts. The Ladies Association, with its well-defined roles, goals, and plans, was an inclusive organization that reached across classes and engaged all women as equally patriotic as men. The association's leadership divided the city into regions, assigning women to go door-to-door and solicit publicly, greatly increasing the visibility of their cause.[3] By allowing all women to participate according to their means, the Ladies raised money from more than 1,400 residents. Less than a month after publishing her broadsheet, on July 4, Esther sent a letter to Washington informing him that the ladies had raised more than 300,000 Continental dollars, with additional funds expected from other states. With this money, the Ladies produced over 2,000 shirts for soldiers in the Continental Army. Perhaps even more critically for George Washington, The Ladies' success re-energized women's support for the war as news of their campaign moved far beyond Philadelphia. Several contemporary letters echoed sentiments similar to those of a woman from Philadelphia, whose letter appeared in the Maryland Gazette: “I have learned more than ever to respect my countrywomen, and there is no title in which I shall hereafter more glory than in that of an American woman.”

The War of 1812 further highlighted the lasting impact of the Ladies of Philadelphia. The conflict spurred women across the country to adopt similar tactics to support the army, including a "subscription paper" to solicit funds and a “Stocking Society” to clothe American soldiers. During the War of 1812, women independently initiated projects, emulating many of the tactics first developed by the Ladies of Philadelphia[4].

While she died soon after the publication of her manifesto and raising funds for the Continental Army, Esther DeBerdt Reed’s contribution to the American Revolution continued as Sarah Franklin Bache became the leader of the Ladies Association of Philadelphia and other women’s groups formed around the country. Today, the Ladies Association of Philadelphia's monetary contribution is widely recognized. However, the more lasting impact was inspiring other women to participate in the political process publicly. Their success showed that women could directly influence political debates, marking a turning point away from women advocating only through their husbands. Their ultimate, if not sufficiently recognized, legacy demonstrated that women could have a pronounced presence in the political arena and laid the groundwork for women’s future political activism and participation in the democratic process.

Further Reading

- DeBerdt Reed, Esther. The Sentiments of an American Woman. Broadsheet, Philadelphia, 1780, Library of Congress (2020769022), https://www.loc.gov/item/2020769022/.

- Arendt, Emily J. "Ladies Going about for Money": Female Voluntary Associations and Civic Consciousness in the American Revolution. Journal of the Early Republic, Volume 34, no, 3 (May 7, 2014): 157–186. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24486686.

- Ireland, Owen. Sentiments of a British-American Woman: Esther DeBerdt Reed and the American Revolution. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017.

- Norton, Mary Beth. Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1980.

- Sklar, Kathryn Kish, and Gregory Duffy. "How Did the Ladies Association of Philadelphia Shape New Forms of Women's Activism during the American Revolution, 1780-1781?" Binghamton, NY: State University of New York at Binghamton, 2001.

- Zagarri, Rosemary. Revolutionary Backlash. Women and Politics in the Early American Republic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

[1] Kathryn Kish Sklar, and Gregory Duffy, "How Did the Ladies Association of Philadelphia Shape New Forms of Women's Activism during the American Revolution, 1780-1781?" Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000 5, no. 1 (2001): 2. https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/womhist.

[2] Owen Ireland, Sentiments of a British-American Woman: Esther DeBerdt Reed and the American Revolution (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017), 179

[3] Emily J. Arendt, "Ladies Going about for Money": Female Voluntary Associations and Civic Consciousness in the American Revolution," Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 34, no. 3 (May 7, 2014), p. 172. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24486686.

[4] Rosemary Zagarri. Revolutionary Backlash. Women and Politics in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennslyvania Press, 2007), 99.