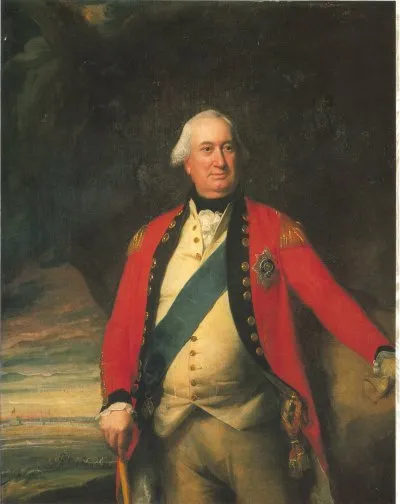

By all accounts, William Howe seemed to be the perfect choice to lead the British Army in its quest to end the rebellion in British North America following the events outside of Boston in April 1775. Coming from a military family and rising within the officer ranks due to his experience in the field, Howe had distinguished himself as a capable general. As he sought to replace Gen. Thomas Gage in Massachusetts, Howe’s objectives were invariably clear: overwhelm the rebels and wait for them to relent their hostilities. In the first year of his command, he certainly seemed to have the upper hand against the Continental Army. However, several factors ultimately cost William Howe his chance of being a British war hero, the man who would restore peace to the colonies.

William was born in 1729 into the family of Emanuel Howe and Sophia Charlotte von Kielmansegg. Sophia was the recognized illegitimate half-sister to King George I, providing the family with a royal prestige that helped carry the Howe name far in British politics. Emanuel inherited a baronetcy claim in 1730, giving him the title of “2nd Viscount Howe,” and served as Governor of Barbados until his death in 1735. William’s two older brothers, George and Richard, grew up in the military tradition, with George rising to the rank of Brigadier General in the British army in the 1750s and Richard becoming an admiral in the Royal navy. George was killed during the British attempt to take Fort Ticonderoga in 1758 during the Seven Years War with France. Highly-respected, George was given honors within North America. Massachusetts helped fund a memorial in his name, something the remaining Howe brothers never forgot.

It seems William Howe won his appointment to succeed Thomas Gage because of a combination of his experience, his family name within the Court of King George III, and because of his attachment to his brother’s legacy – something the Crown hoped to leverage on susceptible colonists. All of these played into his nomination as commander in chief in 1775. His brother, Admiral Lord Richard “Black Dick” Howe, would eventually accompany him to North America, in charge of the British naval fleet. The brothers were given strict instructions from the ministry of British Prime Minister Lord Frederick North and from Secretary of State for North American George Germain. They could issue pardons to rebels who renounced their war against the Crown, but they were forbidden to hold any sort of peace negotiations. The reason for this latter arrangement was the British government did not want to recognize the Continental Congress and Continental army as legitimate entities.

General Howe, along with generals Henry Clinton and John Burgoyne, arrived in Boston at the end of May 1775 with an additional 4,200 British soldiers to reinforce the 5,000 already there under Gage’s command. Having learned of Lexington and Concord, Howe set about trying to isolate the rebels by taking the high ground in and around Boston. This would prevent any Americans from gaining a tactical advantage around the city.

American spies learned of their plan and quickly set to building breastworks atop Breed’s Hill, a steep mount above the village of Charlestown on the peninsula north of Boston Harbor. Overly confident that the superiority of the training and size of the British troops would scare off the rebels, Gage commanded Howe to proceed with a battle plan to land several craft on the eastern bank of the peninsula and march columns of soldiers to take the breastworks. On June 17, as they did, the Americans, holding the high ground, held off two British attempts. A third British assault – one that saw Howe divide his forces into two columns to encircle the top of the hill - forced the Americans to fall back to Bunker’s Hill and over the slender neck of land that connected the peninsula to Massachusetts. The British had successfully taken the hill but lost over 1,000 soldiers in the process.

The victory was severely costly to British morale, particularly to Howe, whose judgment and confidence were perhaps affected for the remainder of the war. Sir Henry Clinton, one of Howe’s subordinates, was also quite critical of Howe’s planning. Clinton had wanted to secure the neck behind the American position to cut off their ability to retreat; however, this suggestion was dismissed, and became one of the many disagreements between the British commanders that inflated their suspicions of one another in the coming years.

At the same time battles raged in Massachusetts, Canada became a priority for both sides. The British wanted to take command of the Hudson River, which would close it to American navigation and effectively cut off New England from the remainder of the continent, essentially containing the rebellion. The Continental Congress assumed the Canadian colonists were equally resentful of their British authorities and would readily join in the cause of the colonies. American efforts proved futile, and the assumptions made by members of Congress were highly audacious.

Gen. George Washington arrived in Cambridge on July 2, 1775, to officially take command of the new Continental forces. As he struggled to build a functioning army, he also had to contend with a lack of artillery among the Americans. Henry Knox, a book store owner in Boston, was given the task of retrieving the heavy munitions from Fort Ticonderoga. Knox’s successful journey —hauling thousands of tons of cannon by oxen through winter conditions from upstate New York to Boston—was nothing short of remarkable. The Americans finally had cannon to strike the British, but what to do with them?

As Washington arrived on the scene, Howe had assumed command of British forces from Thomas Gage. Howe crafted a plan to move operations further south to New York City in the spring of 1776. While spending the winter in Boston, Howe became enchanted with the wife of a loyalist, and other endeavors to pass the time may have taken his focus away from plotting how to rid himself of Washington. By March 1776, Howe knew of the American positions around Boston and became aware of American plans to send two amphibious assaults against the city. At the same time, on the night of March 4, Washington directed his men to build fortifications on Dorchester Heights, the highest point in Boston harbor. Using makeshift sleds, they were able to overcome the late-winter conditions and establish an impregnable foothold that would allow them to fire their cannons into Boston or against the Royal navy moored in the harbor. The next day, seeing what had been built overnight, Howe famously declared, “The rebels have done more in one night than my whole army would have done in a month.”

The British, very wary of another hill-assault following Breed’s Hill, decided against another attack. Howe capitulated and abandoned Boston after securing the promise from Washington that his cannon would not fire on the evacuating British soldiers and ships. Americans proved victorious in the Siege of Boston. While the news was welcomed and celebrated throughout the colonies, both generals knew this was just the beginning of a season of campaigning.

Both sides set their sights on New York City. Washington quickly assembled his army and moved them down into Manhattan and Long Island to fortify the high ground at Brooklyn Heights. Once again, he relied on the topography to buttress his soldiers' lack of experience in battle.

The British waited offshore to allow for reinforcements to arrive, giving Washington precious time to build his fortifications. But what Washington and the rest of the Americans had not counted on was the arrival of the bulk of the British forces sent to reinforce the 8,000 troops already under Howe’s command. Once combined, the British strength totaled 30,000 men and a fleet led by Howe's brother, Richard. As the fleet crept towards the Narrows between Staten Island and Long Island, many Americans commented that it looked like the entire city of London was afloat.

The British landed on Staten Island to establish their beachhead. On August 27, they crossed the mouth of the Hudson River and landed on the southwest corner of Long Island. From there, Howe, along with Clinton, moved a large portion of their army around the left flank of the American positions. As the Continental forces concentrated their efforts on the British columns in front of them, Howe’s army moved undetected. The Americans did not see them until it was too late. Confusion and inexperience gripped the American ranks (not the last time this would happen facing Howe), and the army was pushed back behind the fortifications at Brooklyn Heights. Thinking he had the Americans beaten, Howe called off any further advances for the day, despite protests from Clinton and Maj. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis. In a stroke of bad luck for the British, the American army silently evacuated the west bank of Long Island in the early morning hours of September 28. When the British awoke and advanced, they found an empty shoreline. In the coming weeks, Howe's success continued, as he drove the Americans from Manhattan Island to its northern outskirts. Howe received the title of Sir William Howe following his victories in New York, which became the new command center of British operations for the war.

Washington escaped through New Jersey and settled on the western banks of the Delaware River in Pennsylvania. He started the New York campaign with a force of 12,000 men. By December, his forces were below 3,000. Those who hadn’t been taken prisoner or died from battle or disease had deserted. Unless something was done, the remainder of his men were likely to walk away at year’s end when their enlistments expired. It was the darkest hour for the American cause.

For the British, the rebellion seemed to be coming to end. Howe extended a series of garrisons throughout central New Jersey; a string of detachments running from New Brunswick west to Princeton, Trenton, and then south to Bordentown. He placed these garrisons in the hands of Hessian and Scots troops, soldiers of fortune hired by the British government to help them win the war. Howe remained confident the 3,000 or so soldiers could manage any skirmishes that broke out over the winter months. But despite some clear indication that Washington was planning an attack, no one within the British chain of command took it as a serious threat. The events that unfolded between December 26, 1776, through January 3, 1777, changed the course of the war and history forever. With two victories at Trenton and Princeton, Washington saved the war for American independence, and subsequently gave the British command a serious black eye.

In the spring of 1777, British forces moved into New Jersey to try and draw Washington out of his hiding place in the northern foothills of the state and into a major engagement. On June 26, after weeks of Howe failing to engage him, Washington advanced as the British withdrew to Staten Island. Sensing his chance, Howe swung the entire army around and marched on the Americans near Metuchen, New Jersey. The Battle of Short Hills was short-lived, much to the frustration of Howe and Cornwallis, as Washington quickly retreated into the mountains before the main British forces arrived. Fed up, Howe quit New Jersey and moved to New York to regroup.

Howe’s strategy during the time he was commander in chief has been ridiculed and highly debated among historians. While it is clear he was a capable leader, it is also clear that he gave Washington too many chances to retreat or regroup at precious moments where a more aggressive British response could have produced a drastically different outcome. Whether this is legitimately fair to Howe remains up for debate; the British commander was fighting a war based on eighteenth century military principles. He was also unprepared, as was nearly the entire British command, to fight an insurgency and guerilla war on a vast continent that would be nearly impossible to contain from an ocean away.

To cripple the rebellion, Howe turned to Philadelphia, the rebel capital. Washington knew this too. In July 1777, Howe's forces set sail for the Chesapeake Bay and planned to march from the south to attack Pennsylvania. Once again, Howe gave Washington time to plan his defenses. The British landed at Head of Elk, Maryland in late August, and marched northward. Howe’s army approached Chadds Ford from the southwest on September 10. The Continentals under Washington had positioned themselves on the eastern bank of Brandywine Creek. On September 11, the largest battle of the Revolutionary War commenced. And once again, Sir William Howe deceived the American commander.

Washington had made note of the creek's crossing points where the British might try to cross and flank them. However, some of the scouts missed a ford north of the American position, which turned out to be the one that Gen. Howe exploited brilliantly during the battle. Much like what happened in Brooklyn, while one portion of the British army engaged the Americans head on, Howe swung to the right around the American lines and flanked them from the north with a large detachment of troops. It took the Continentals by complete surprise and quickly altered Washington’s plans. Seeing the battle was lost, Washington ordered the retreat and the main American forces fell back as other detachments fended off Howe’s advance. What promised to be a major battle turned into a decisive victory for the British. Howe had beaten Washington with the same maneuver, again.

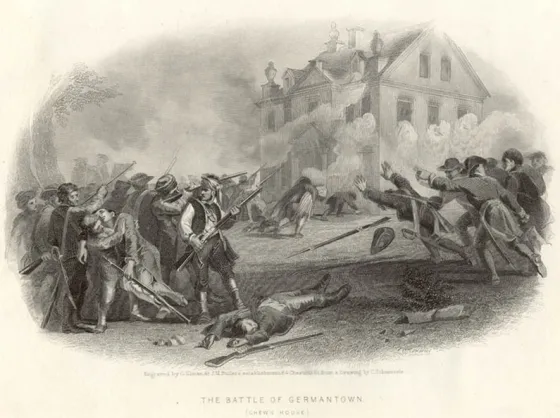

In the coming weeks, the Americans tried to entice Howe into another major engagement. Torrential rains and a misjudged mission that led to American Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne’s forces being annihilated at Paoli led to an unceremonious taking of Philadelphia by the British on September 26. Washington tried one more time to draw Howe into a major fight, but his efforts on October 4, 1777, at Germantown failed. As the winter months approached, the Americans slunk into their winter encampments west of the city at Valley Forge while Howe and the British enjoyed the comforts of Philadelphia.

All was not well, however. Further north, a British army of 8,000 troops under the command of Gen. John Burgoyne had been badly beaten and forced into a humiliating surrender at the hands of American Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates at Saratoga. Burgoyne’s army had been in desperate need of supplies and reinforcements, and after being unable to navigate the hostile countryside, they positioned themselves to defend against an increasingly overwhelming American presence. The ripple effects of this British defeat were immediately felt in Paris, where American diplomats had been courting the French government for military support and sovereign recognition. After Saratoga, King Louis XVI formally declared his support of the United States, transforming the rebellion into a potential world war.

Howe had been instructed to reinforce Burgoyne in the spring of 1777, but the British commander instead planned to take Philadelphia to force the rebel government to capitulate. Burgoyne and the British government were under the initial impression that Howe intended to send reinforcements north to Burgoyne. Instead, Howe settled on taking Philadelphia, inhibiting coordination between his army and Burgoyne's forces.

When Howe learned of Burgoyne’s defeat in October 1777, he tendered his resignation as commander in chief. He, along with the British, remained in Philadelphia until late May. On May 18, 1778, a huge festive party was thrown in his honor, known as the Mischianza. Howe departed for London on May 24, and his subordinate, Sir Henry Clinton, took over as commander in chief of the British Army in North America.

Along with his brother Richard, who also resigned, the Howes faced censor and court-martial upon their returns to England. Howe spent years defending his leadership in the British press. He regained his stature within the British army and serve during the French Revolutionary Wars before retiring and dying childless in 1814.

Despite how his tenure ended, it must be said that Sir William Howe acted ably, given his knowledge and military training. What is inexcusable was his inability to view the war in terms beyond his own personal doings. Certainly, he was not alone in this manner, which helps us explain how separate commands and conflicting messages from a distant government plagued British hopes of winning the war. Had he been more aggressive, it is plausible Sir William Howe would be remembered as the British general who put down the American rebellion; rather than one of the generals who lost England her American colonies.

Further Reading

- Washington’s Crossing By: David Hackett Fischer

- The Enigma of General Howe By: Thomas Fleming

- The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution By: Ira D. Gruber

- Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777 By: Michael Harris

- The Philadelphia Campaign: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia, Volume 1 By: Thomas J. McGuire

- The Philadelphia Campaign: Germantown and the Roads to Valley Forge, Volume 2 By: Thomas J. McGuire

- The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution and the Fate of the Empire By: Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy

- Whispers Across the Atlantick By: General William Howe and the American Revolution: David Smith

- William Howe and the American War of Independence By: David Smith

- Washington Plays Hardball with the Howes By: John L. Smith, Jr

- The Philadelphia Campaign, 1777-1778 By: Stephen R. Taaffe

Related Battles

450

1,054