“T hat possession of the hill called Bunker’s hill in Charlestown, he securely kept and defended, and also, some one hill or hills on Dorchester neck be likewise secured…” came the missive of a committee of the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in early June 1775. This de-facto political body left it to the Council of War, which comprised General Artemas Ward, the ever-present Dr. Joseph Warren, and the other generals stationed around Boston. These military officers should do whatever was necessary “for the security of this colony.”

By the middle of June, word reached Jonathan Hastings House, where Ward had set up his headquarters following the actions of Lexington and Concord in April. From a “gentleman of undoubted veracity” who had been able to leave Boston on June 9, the message arrived in Ward’s hands on June 14. British General Thomas Gage had planned an offensive on Sunday, June 18, against Dorchester Heights, to the south of Boston and then subsequently at Charlestown with the hope of advancing on Cambridge and scattering the rebels.

After consulting with General John Thomas and William Heath, both in charge of Patriot defenses near Dorchester Heights in Roxbury, Ward realized that nothing could be done to stop the British in that sector. The Americans lacked necessary supplies of war to repel and defend the prominence, including a lack of artillery. Ward focused on defending Charlestown, which included fortifying Bunker Hill.

Charlestown was “vital for the survival of the rebel army.” Cambridge lay barely three miles farther along, and whoever controlled the heights of Charlestown also controlled any movement or occupation of Cambridge. In turn, Bunker Hill dominated the peninsula, looked over parts of Boston, and was also out of artillery range of most of the British ordnance. Lastly, if the Americans could take the initiative and preempt Gage’s planned offensive, then Dorchester Heights may be forgotten and British efforts focused on pushing the rebels from Charlestown.

In his councils at Hastings House, Ward settled, with his generals, on sending the three Massachusetts militia regiments, under the commands of Colonels William Prescott, Ebeneezer Bridge, and James Frye, numbering approximately 1,000 men. Joining with the Massachusetts men was a contingent of Connecticut militia overseen by General Israel Putnam and Colonel Richard Gridley’s company of artillery. Prescott was in overall command, with Gridley overseeing construction of fortifications. The militia infantrymen held their postings the first day on Bunker Hill.

These men at 6:00 p.m. marched onto Cambridge Common, and shuffled into line within sight of the Hastings House. Although not the most military-esque, these men believed in their officers and followed them toward the looming height of Bunker Hill. Ward had made his move; the rebels would provoke the British by clandestinely erecting earthworks on Bunker Hill.

What about the British? Reinforcements trickled in throughout May, bringing the eventual number to 6,000 men within the environs of Boston. Along with the rank-and-file came three general officers, William Howe, Henry Clinton and John Burgoyne by May 25, 1775. Planning began almost instantly to break the ring of enemy militia encircling the city, what Burgoyne would write as creating “elbow room.”

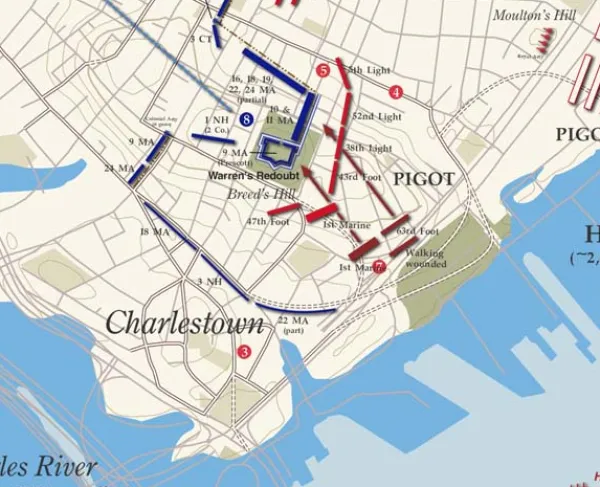

Decisions had been made by the brass of the British military in Boston to assault Dorchester Heights and then move on to assault Charlestown. Yet, as the sun crested the eastern horizon on June 17, sentries and observers notified Gage about what the militiamen of New England had accomplished. A redoubt had been constructed on Breed’s (Bunker) Hill, which prompted the British into action.

At approximately 9:00 a.m., a plan of action was decided upon. Howe would personally lead troops across the Charles River to attack the newly constructed redoubt. The British Navy opened the day’s actions by starting a cannonade that lasted approximately two hours.

For the victorious British, Bunker Hill was the first of several Pyrrhic victories in the ensuing American Revolutionary War.

Those two hours though were not enough for the infantrymen and marines of the British military. First, the tide was insufficient for the British Navy to ferry the foot soldiers to the Charlestown Peninsula until midday. After the 2,400 soldiers landed, terrain of fences, swampland and a narrow strip of beach funneled them toward a reinforced fence. Lastly, the British Navy found its guns could not provide the necessary prelude of covering fire that Gage and the British leadership had hoped would soften the American defenses.

With the approach of and unexpected delay of the British attack, militia reinforcements arrived to bolster the number of defenders. Showing an understanding of the lack of combat experience of their men, some colonial officers ventured toward the front slopes of Breed’s Hill, planting stakes to mark the location of when to fire at the enemy.

Drums sounded around 3:30 p.m., and British forces launched themselves toward the hill and the rail fence running perpendicular to the Mystic River and on the left of the American line. What ensued was a two-hour engagement that ended with American withdrawal and a short-lived pursuit by the weary British soldiery. On the hillside of Breed’s Hill and along the stretch of sandy soil on the bank of the Mystic River laid more than 1,000 dead and wounded British soldiers. Approximately 450 colonials were killed and wounded, including the great Patriot Dr. Joseph Warren, so instrumental in the build-up of Massachusetts and the burgeoning revolutionary movement. He had risen from his bed, where he had been laid-low with a migraine, to rush to Breed’s Hill, where he was one of the last to fall as the redoubt itself fell to the British.

For the victorious British, Bunker Hill was the first of several Pyrrhic victories in the ensuing American Revolutionary War. The sight of a carpet of red strewn on the Charlestown Peninsula would be an embedded memory to Howe, soon to take over the top mantle from Gage, of the British war effort in North America. That high attrition of casualties potentially played a role in some of the future campaigns Howe conducted against the Continental Army in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

Although a British victory, Bunker Hill has entered the pantheon of American military lore. Probably the most positive outlook of any American military defeat in the country’s 250-year history. In popular culture, the name Bunker Hill ranks with such great American victories as Gettysburg and the actions of D-Day in World War II. Its memory solidified the prowess and capability of the militia and bookended the actions of Lexington and Concord two months prior.

The memory, history and importance of Bunker Hill, though, is best summed up by General Nathanael Greene, who spoke for the multitude wanting American independence. “I wish we could sell them [the British] another hill at the same price.”

Related Battles

450

1,054