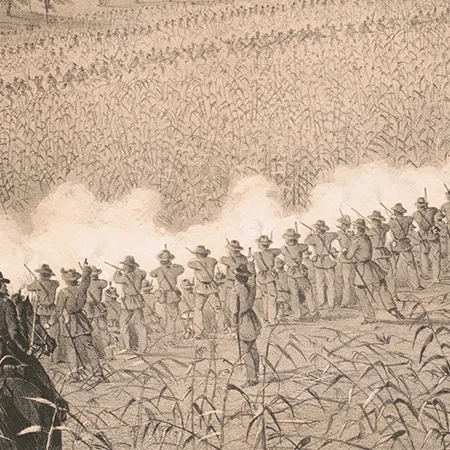

The First Battle of Cynthiana, from “Illustrated History of the Civil War.”

After the early Federal successes at Mill Springs, Middle Creek, Forts Henry and Donelson, and turning back the Confederates at Shiloh, by the summer operations had ground to a slow pace. When Corinth fell in May Henry Halleck had made the decision to split his large army to engage in disparate operations, one of those being Don C. Buell’s advance across northern Alabama to take the vital city of Chattanooga. Due to the heat of the summer and the need to repair the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, designated by Halleck to be the main supply artery for Buell’s command, Buell’s command crawled towards Chattanooga. It was during this slow Federal movement that John H. Morgan led his command on what is known as the First Kentucky Raid.

Morgan’s force had grown from a squadron-sized force to a small brigade with the expansion of his squadron into the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, the addition of a battalion of Georgia partisan rangers, and a mixed squadron of Texans and Tennesseans. After Shiloh, Morgan had been assigned to Edmund K. Smith’s East Tennessee department, and here began the morphing of Morgan’s men into a mounted infantry force, shunning traditional cavalry tactics. With Morgan were two men destined to instill the discipline necessary to conduct successful raids into the enemy’s rear – English soldier of fortune George St. Leger Grenfell and Morgan’s brother-in-law Basil Duke. It was said if you knocked Morgan on the head, it would be Duke’s brains that would spill out, showing the importance Duke had in the decision-making process of Morgan’s command.

It was decided that Morgan would raid into Kentucky, sowing confusion and creating destruction, to retard Buell’s movement towards Chattanooga. On July 4th, 1862, Morgan started from Knoxville, moving across northern Tennessee to Sparta, then crossing into Kentucky south of Tompkinsville and moving towards that town where Morgan gobbled up a portion of the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry by splitting his command in two, sending a portion to get into the Pennsylvanians’ rear, a common tactic for Morgan’s men.

Moving northward towards Horse Cave and while here one man in his command would earn the nickname “Lightning.” George Ellsworth, a Canadian who was an expert telegraph operator, could tap in the telegraph lines, read transmissions, as well had the ability to mimic other operators’ key style (known as a fist) and then use this ability to send false messages about Morgan’s movements and size of his force along the wire. Near Horse Cave, Ellsworth tapped a line along the Louisville & Nashville Railroad during a thunderstorm. With water up to his knees and the thunder and lightning exploding all around, he kept at his task, thus earning his nickname. This use of the telegraph would cause great consternation among Union forces in the state, and Abraham Lincoln would message Halleck on July 13th: “They are having a stampede in Kentucky. Please look to it.”

Morgan, known for his playful nature also used the telegraph to taunt Federal commanders, such as Jeremiah T. Boyle, the military district commander of Kentucky. On one occasion he would have Ellsworth send the following message: “Good morning, Jerry. This telegraph is a great institution. You should destroy it as it keeps me posted too well. My friend Ellsworth has all your dispatches since July 10 on file. Do you want copies?”

From Horse Cave, the Confederates would move through Lebanon, Harrodsburg, Versailles, Midway, before arriving at Georgetown on July 16th. Such was the outpouring of support along the way, particularly from the women at Harrodsburg, that Morgan would send the following message to Smith from Georgetown:

I am here with a force sufficient to hold all the country outside of Lexington and Frankfort. These places are garrisoned chiefly with Home Guards. The bridges between Cincinnati and Lexington have been destroyed. The whole country can be secured, and some 25,000 or 30,000 men will join you at once. I have taken eleven cities and towns with heavy army stores.

While prominent Kentuckians had been clamoring for Confederate support for months, this message would be the tipping point that would convince Smith that a summer campaign into Kentucky would yield increased military support to the Confederate ranks. Smith would meet with Braxton Bragg in Chattanooga, and the Perryville Campaign would be the result.

On the morning of July 17th Morgan moved his forced northeast from Georgetown towards Cynthiana, a small town along the South Fork of the Licking River. The Kentucky Central Railroad also cut through town, this line being a key supply avenue for any Federal advance into eastern Tennessee. Morgan was familiar with Cynthiana, having had pre-war business dealings in the region as well as having participated in a State Guard encampment in 1860 north of town. Cynthiana offered southern support, as well as a road network that would allow Morgan to move in any of several directions, providing the Confederates flexibility in movement.

Arriving three miles south of town Morgan would split his command into three parts. The Georgia battalion, with one company of Kentuckians, all under command of F. M. Nix, would swing to the west and move north of Cynthiana, breaking up a Federal supply camp. The Texans and Tennesseans, being led by Kentucky native Richard M. Gano, would move to the east, coming into town along the Millersburg Pike. Morgan, with Duke and the bulk of the Second Kentucky Cavalry, would advance along the Leesburg Pike. Morgan’s small brigade numbered 900 men and included an artillery section of six-pound mountain howitzers, known affectionately as “bull-pups.”

Facing Morgan in Cynthiana was a collection of Home Guards and raw recruits. This force, about half the size of Morgan’s brigade, consisted of five companies of Home Guards (including police and firemen from Cincinnati), a squad of the 18th Kentucky Infantry, seventy-five newly recruited troopers for the 7th Kentucky Cavalry (USA), and about one hundred civilians impressed into service. There was artillery support in the form of a twelve-pound howitzer, manned by those red-shirt-wearing firemen from Cincinnati. The Federal force was under command of Lieutenant Colonel John J. Landram of the 18th.

Duke would launch an attack from the south bank of the river, trying to cross the 320-foot-long covered bridge with a mounted force. This attack was beaten back by the firemen and their howitzer and the Home Guard which had been deployed on the various buildings along the north shore. Duke would shake out four companies on foot to attempt to cross the river, but the river, with its steep banks and waist-deep water, was difficult to cross. More attempts to cross the bridge were foiled, causing Duke to write “A company of firemen from Cincinnati went to work when the fight opened as if they were ‘putting out a fire.’” Finally, the Confederates were able to find a ford near the bridge, and Company A of the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry were able to wade across, but after making a lodgment on the north bank were unable to press forward in the face of Home Guard resistance. One of the bull-pups was brought up near the south end of the bridge, but its crew was driven away by a volley from the Home Guard. Company C, mounted, was finally able to storm across the bridge but once in town milled about not knowing which direction to head. Enter into the fray George St. Leger Grenfell, who, perhaps under orders from Morgan, “came galloping up, having crossed the river at another point, and directed Capt. Bowles on how to reach the depot street. The charge was again ordered and the company on all sides surrounded by the enemy in houses charged on horseback a depot filled with Yankee infantry. The enfilading fire was very severe, the firing from the depot was checked somewhat by our almost reckless charge and as it was impossible for horsemen to ride into the building, we continued our ride entirely through the town, subject all the time to a severe fire from every side of us.”

By this point both Nix’s and Gano’s commands made their appearance, causing the Federal defenders to reduce their defensive perimeter. Nix had captured nearly seventy men near the Episcopal Church and marched them towards Main Street. Part of Nix’s command pushed other Federals towards the railroad depot where Landram was making a final stand. Nix then joined Duke and Gano in surrounding the depot, where the defense was down to thirty men. The Cincinnati firemen had moved their gun from near the bridge to face Nix’s troopers to the north, then moved the gun eastward along Pike Street, and were in front of the Rankin House (a large hotel), when Gano’s men rushed the gun, capturing it. Landram, wanting to get a better view of the fighting, moved from the depot north along the Kentucky Central towards the Rankin House as it was a three-story structure. Before reaching the house, Landram met a Confederate officer on horseback who demanded Landram’s surrender, to which Landram replied “I never surrender” and fired three shots at the rebel, two of them striking his chest. The officer amazingly survived. Landram, mounted on a fine horse, led his remaining men, most likely not mounted, southeast out of town. He was pursued for ten miles before making his escape.

The fighting was now over, and the Federals surrendered after 60-90 minutes of fighting. Morgan’s men marched the captured Federals and placed them on the second floor of the courthouse. One Federal prisoner, seeing the ladies of the town supply Morgan’s men with pies and cakes, but not offering any to the prisoners, stated “Perhaps those ladies did not know that Yankee soldiers liked pie and cake.”

Morgan had fought a successful engagement but also saw what Home Guard could do when defending in a town setting. Confederate losses were 40-50 killed and wounded, while the Federals suffered 50-60 men casualties, with the remainder being captured. There was some plundering of necessary items (such as boots and shoes), a large number of butternut jeans was taken from a merchant, and a newspaper claimed that every Confederate “went away with a new pair of pants and a load of clothing piled up before him on his horse.”

Morgan spent the night of July 17th in Cynthiana, most likely using the Old Rankin House as his headquarters. On the 18th the command arrived in Paris and camped overnight. Union General G. Clay Smith, with 1800 men, moved into Paris just as Morgan’s command was leaving via the Winchester Road, narrowly avoiding another battle. Smith’s approach to Paris had been timid, and a more aggressive commander might have caused Morgan’s reduced command to either fight or flee. Smith’s timidity at Paris was a microcosm of the Federal response to the raid.

Morgan’s troops had ridden over 1000 miles in twenty-four days. It was a successful raid in many respects – he did secure recruits and horses for his command and was able to report the general (albeit mostly female) support that the Bluegrass had shown. He had used electronic warfare to sow confusion. He had created a command that was well versed in mounted infantry tactics while developing their esprit de corps. And he added to his own legend of being the Thunderbolt of the Confederacy.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...

Related Battles

262

552

42

21

2,691

13,846

5,824

8,000

4,211

3,401