Arnold’s March to Quebec

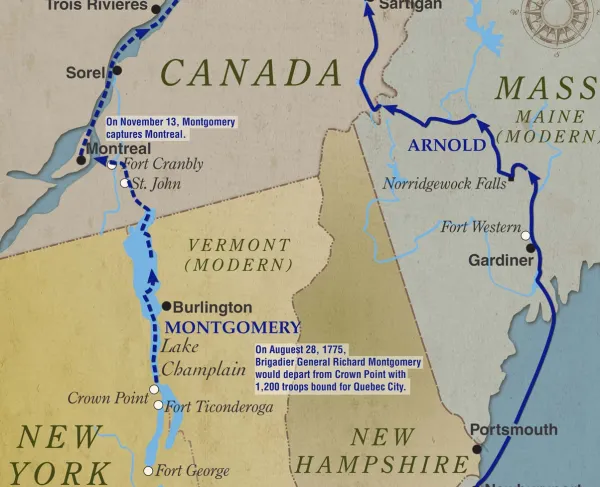

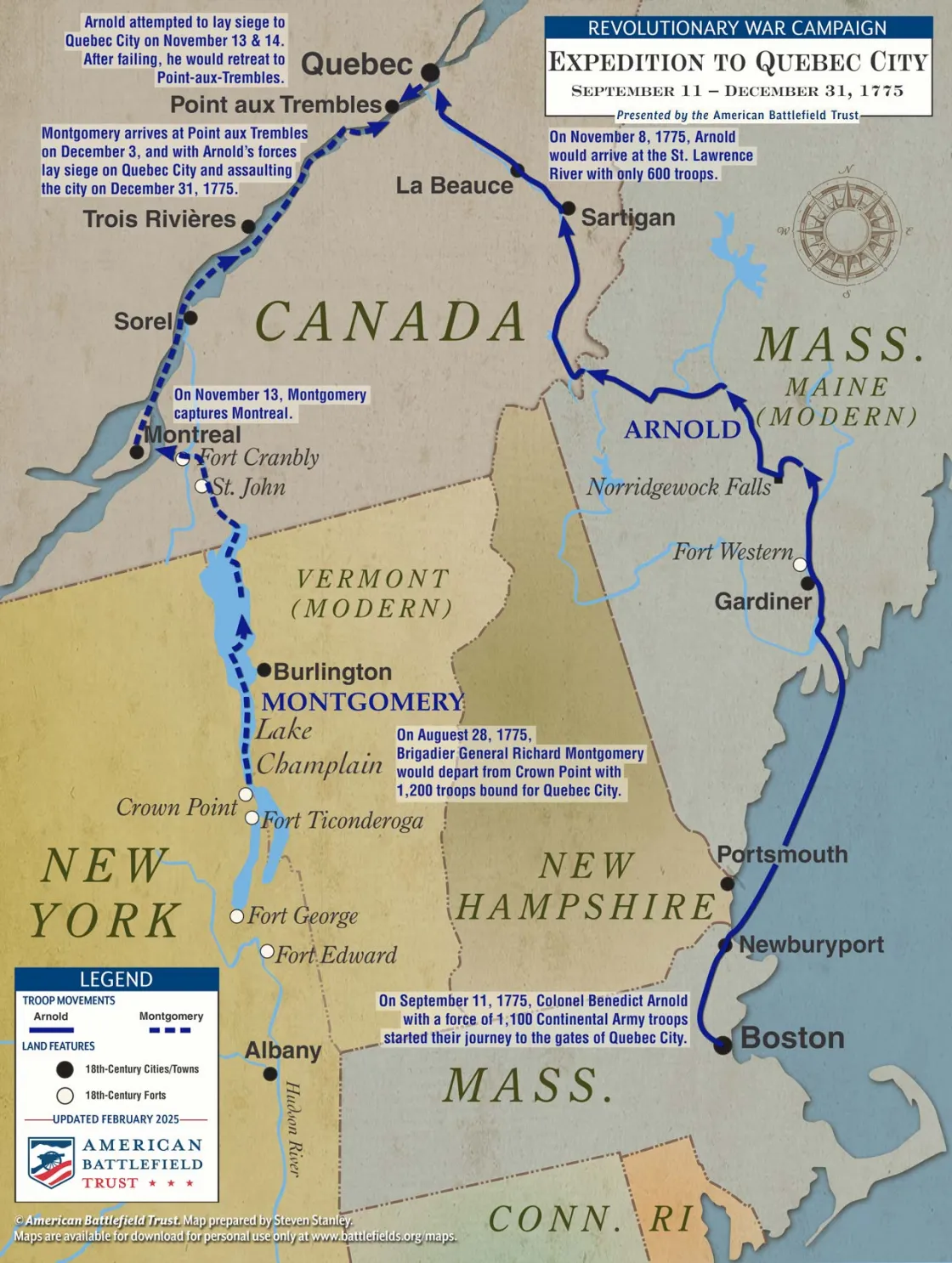

Sailing from Massachusetts, the expedition first travelled up the Kennebec River and across the Maine wilderness. Their goal: the capture of Quebec City, depriving the British of a strategic base to the north. And, perhaps, French Canadians in Quebec would be inspired to join the rebellion.

The Embarkment

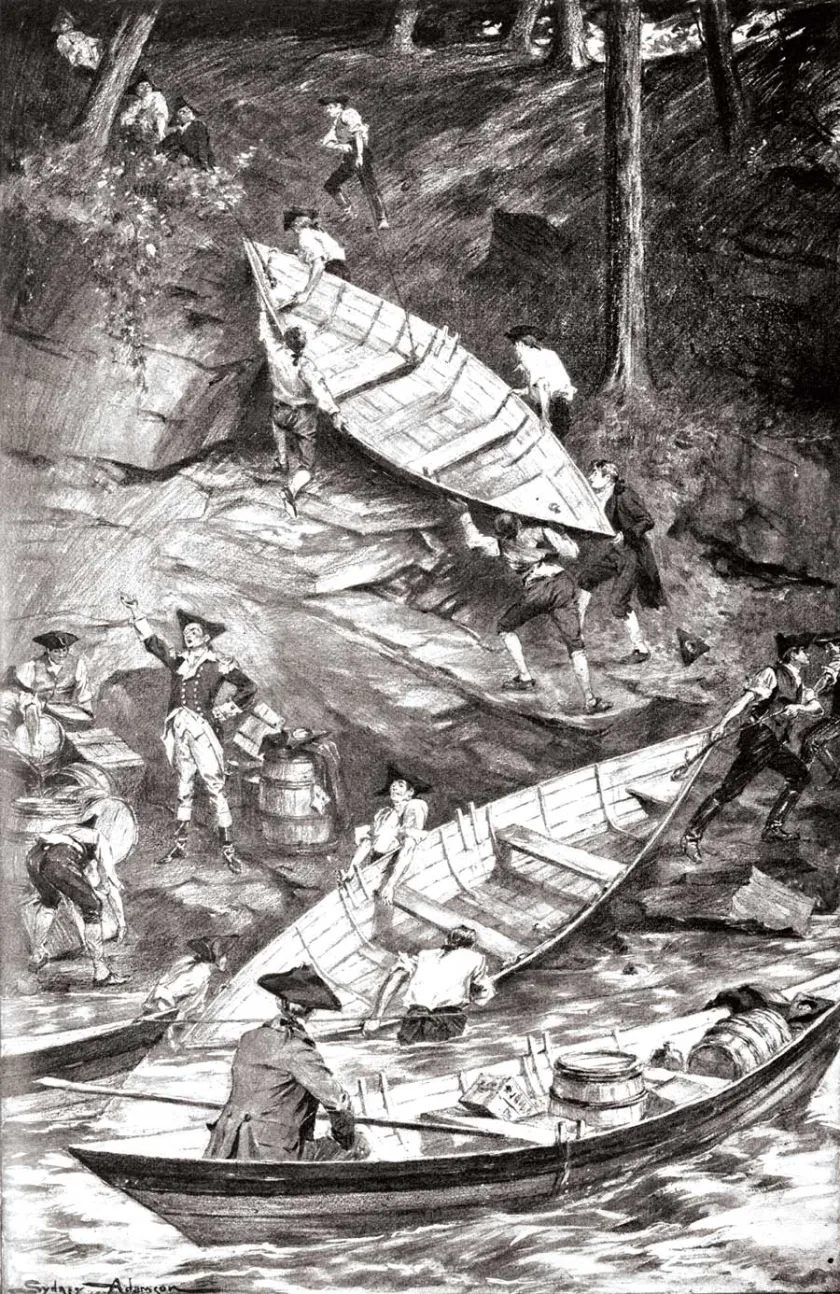

On September 19, 1775, Benedict Arnold’s army — consisting of two battalions of musketeers, led by Lieutenant Colonel Roger Enos and Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Greene, and three rifle companies led by Captain Daniel Morgan — departed Newburyport, Massachusetts, for Maine. As Joseph Ware, a private from Needham, Massachusetts, recorded in his journal: “[O]ur fleet consisted of eleven sail of vessels,— sloops and schooners; our number of troops, consisted of 1300 and 11 companies of musketmen and three of riflemen.” Sailing up the Kennebec River to Pittston, the expedition reached the home of boatbuilder Reuben Colburn on September 22. Back in August, Arnold himself had contacted Colburn, writing: “[W]ithout Delay proceed to The Constructing of Two Hundred Batteaus, to row with Four Oars each; Two Paddles and Two setting Poles to be also provided for each Batteau.”

Arnold and his officers met with Colburn to inspect the bateaux, but all was not well. As Arnold wrote to George Washington toward the end of September:

“I found the Batteaus compleated, but many of them smaller than the Directions given, & very badly built. of Course I have been obliged to order twenty more, to bring on the Remainder of the Provisions, which will be finished in three Days.”

Today, the Colburn House stands as a testament to this historic expedition. In 1969, a 501(c)(3) corporation called The Arnold Expedition Historical Society (AEHS) was formed to preserve sites and trails along the Arnold Trail to Quebec. The AEHS established its headquarters at the Colburn House State Historic Site in Pittston, Maine — the very location where the expedition’s bateaux were built. Managed by Maine’s Bureau of Parks and Lands, the Colburn House is one of the region’s oldest structures. The AEHS has transformed the site’s barn into a seasonal bateau workshop and museum. In 2025, with funding from the Americana Corner Preserving America Grant program, the AEHS built a new bateau display — featuring a replica of an 18th-century bateau — on-site.

Up the Kennebec

Moving upriver, the expedition arrived at Fort Western — an old wooden stockade in what is now Augusta, Maine. As remembered by Caleb Haskell, a solider from Newburyport:

“September 24th, Sunday.—This morning I took my pack, travelled to Fort Weston, where we encamped on the ground. Several of the companies have no tents here. We are very uncomfortable, it being rainy and cold and nothing to cover us.”

On September 25, Arnold reorganized the two battalions into four divisions, reasoning that smaller units could be staggered to prevent bottlenecks at portages and campsites along the route. (Arnold would later direct Enos’ division, which carried most of the expedition’s supplies, to act as the rear guard.) The units planned to rendezvous at Chaudière Pond and proceed to Quebec as one army.

Over the next few days, members of the expedition headed north, by land and by bateaux, to Fort Halifax, perched at the confluence of the Kennebec and Sebasticook Rivers in present-day Winslow. The troops paused to rest and resupply before continuing their arduous journey upriver.

Old Fort Western still stands as the oldest surviving wooden fort in the United States. Each year, visitors explore its barracks, trading post and blockhouses — small, enclosed fortifications with openings for defense. In time for the 250th anniversary of the Arnold expedition in 2025 and the United States Semiquincentennial in 2026, various artifacts found along the Arnold Trail to Quebec and collected by the AEHS — including ax heads, buttons and cutlery — are being displayed to the general public at Old Fort Western.

The sole remaining blockhouse at Fort Halifax State Park in Winslow — the oldest blockhouse in the nation — continues to attract the curious. The site’s appeal was enhanced in 2025 by a new bateau display built by the AEHS and The Friends of Fort Halifax, with grant funding from the Elsie & William Viles Foundation in Augusta.

Painful Portages

Heading upriver, the bateaux began to reveal serious flaws. As recorded by Dr. Issac Senter, the expedition’s surgeon:

“[S]everal of our batteaux began to leak profusely, [being] made of green pine, and that in the most slight manner. Water being shoal and rocks plenty, with a very swift current most of the way, soon ground out many of the bottoms.”

After navigating several smaller portages, members of the expedition reached the infamous Great Carrying Place portage on October 6.

This brutal portage covered nearly 12 miles across boggy terrain and rocky ridges, with the expedition threading its way past East, Middle and West Carry Ponds. The landscape was unforgiving: Dense spruce and hemlock crowded the narrow path, while slippery roots and fallen logs turned every step into a trial. On October 14, Dr. Issac Senter wrote:

“The army was so much fatigued, being obliged to carry all the batteaux, barrels of provisions, warlike stores, &c., over on their backs through a most terrible piece of woods conceivable. Sometimes in the mud kneedeep, then over ledgy hills, &c.”

The suffering multiplied as exposure, hunger and exhaustion took their toll. With the ranks thinned by sickness and injury, the officers ordered the construction of a small log hospital near East Carry Pond to shelter the increasing numbers of sick and disabled men.

The portages slowed progress to a crawl and depleted stores much faster than anticipated. Provisions spoiled in the leaking boats, and the men, already exhausted, now faced the stark reality of dwindling food. The soldiers caught trout, hunted game and foraged for whatever they could find.

On October 13, Arnold wrote George Washington, updating him on the expedition’s slow progress:

“Your Excellency may possibly think we have been tardy in our March, as we have gained so little, but when you consider the badness & weight of the Batteaus and large Quantity of Provissions &c. we have been obliged to force up against a very rapid Stream, where you would have taken the Men for amphibious Animals, as they were great Part of the Time under Water, add to this the great Fatigue in Portage, you will think I have pushed the Men as fast as they could possibly bear. The Officers, Volunteers and privates in general have acted with the greatest Spirit & Industry.”

In the summer of 2011, AEHS members surveyed the site of the hospital with metal detectors and found various artifacts, including musket balls, musket parts, a broad axe and parts of a cast-iron kettle.

Today, the AEHS works to clear, preserve and promote the Great Carrying Place portage trail — and in the summer and autumn of 2025, the organization led members of the public on guided hikes along the trail in honor of the 250th anniversary of the expedition.

The Dead River and Beyond

On October 16, Arnold’s party crossed the “Savanna,” an extensive open marsh with scattered islands of spruce. After much struggle, they reached a small stream, Bog Brook. Then, canoeing for less than a mile, they arrived at the Dead River.

On October 19, the weather took a turn for the worse. Rain began to fall heavily, and the river swelled from the downpour.

Two days later, at 4:00 a.m., Arnold woke to the sound of rushing water. He and his men scrambled to higher ground as the river overflowed its banks. A wall of water rushed down the river. Casks of food, gear and bateaux washed away. Dr. Senter recalled how “the number of batteaux were now much decreased. Some stove to pieces against the banks, while others became so excessive leaky as obliged us to condemn them.”

On October 23, with hunger mounting and supplies running low, Arnold considered ending the expedition. Calling his officers together for a council of war, he argued that, despite their hardship, they should continue toward Canada. The officers agreed. To save the mission, they decided to send an advance party ahead to French settlements on the Chaudière River to seek help and bring back supplies. Those who were too sick or too weak to continue were ordered to return to American settlements in Maine.

As Joseph Ware recorded in his journal:

“Our provisions growing scanty, and some of our men being sick, held a council and agreed to send the sick back, and to send a Captain and 50 men forward to the inhabitants as soon as possible, that they might send us some provisions. Accordingly the sick were sent back, and Capt. Handchit with 50 men sent forward. Before this Col. Enos, with three captains and their companies turned back and took with them large stores of provisions and ammunition, being discouraged, (as we supposed) by difficulties they met with. This day got forward nine miles. The water very rapid and many of our boats were upset, and much of our baggage lost and provisions and guns.”

After departing the Dead River, Arnold’s troops traveled north through a series of highland lakes known as the Chain of Ponds, then through an area of eskers, or ridges, and other bodies of water until they reached present-day Arnold Pond. Canada — and the rest of the expedition’s grueling mission — lay just beyond the mountains.

In the summer of 2016, AEHS member Kenny Wing scouted one of these eskers with a metal detector and recovered what was thought to be an iron ring associated with a bateau setting pole. In the autumn of 2024, the AEHS partnered with the Maine Historic Preservation Commission to resume investigating the esker. This project yielded additional artifacts associated with the expedition: another iron ring; an iron spike that may have been set as the point of a setting pole; and two lighter iron rings with holes on either side, which may have been fitted on the handle end of a setting pole. In 2025, the AEHS began an underwater search of Arnold Pond for remains of damaged or discarded bateaux. This process will continue into 2026. For further updates, please visit the AEHS website at https://arnoldsmarch.org.

Legacy of the Arnold Trail to Quebec

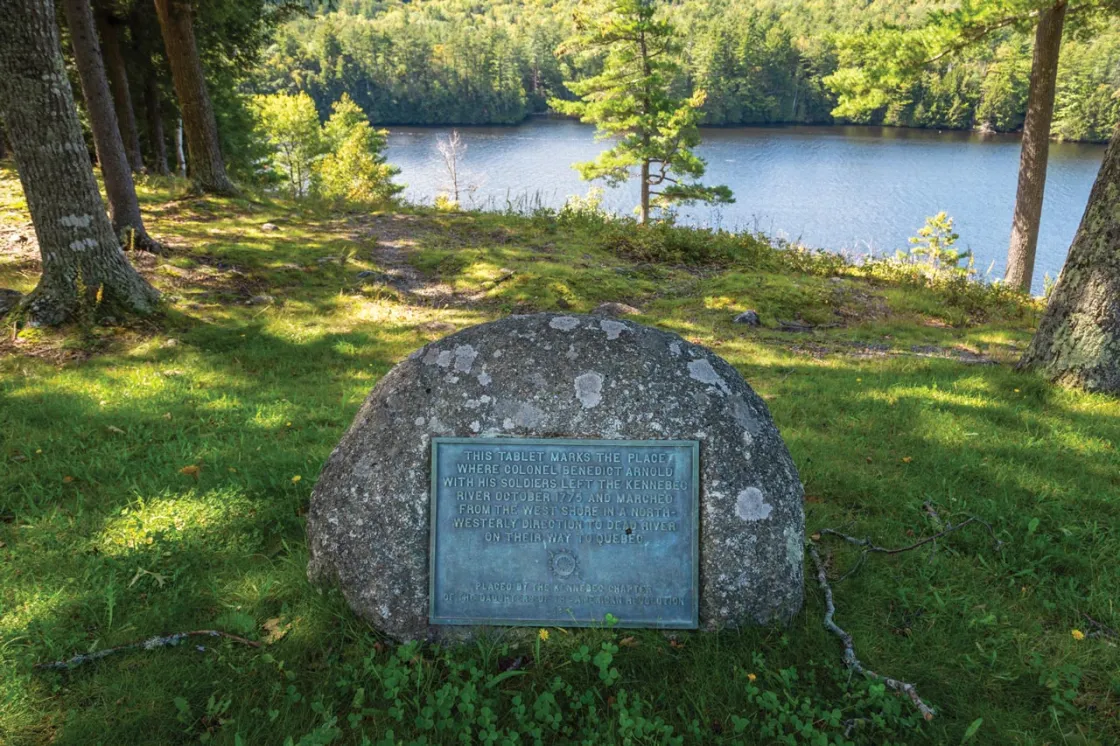

In the early 1900s, the Daughters of the American Revolution began placing markers in Maine along the Arnold Expedition’s route. In recognition of its historical significance, the Arnold Trail to Quebec was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

Today, the Arnold Trail to Quebec serves as both a commemorative and educational corridor, stretching through Maine’s remote wilderness and offering a tangible link to the past. Preservation efforts have ensured that sections of the original route remain accessible to the public, and local historical societies continue to interpret the expedition’s legacy through signage, guided tours and annual events. For outdoor enthusiasts and history buffs alike, portions of the trail are open for hiking, paddling and exploration, allowing visitors to experience the same rugged landscape that challenged the Arnold Expedition.

The Arnold Trail to Quebec is a living classroom — inviting students, history enthusiasts and travelers to engage personally with the landscape and reflect on the meaning of endurance, cooperation, ambition and patriotism.