Knox Expedition, Noble Train of Artillery

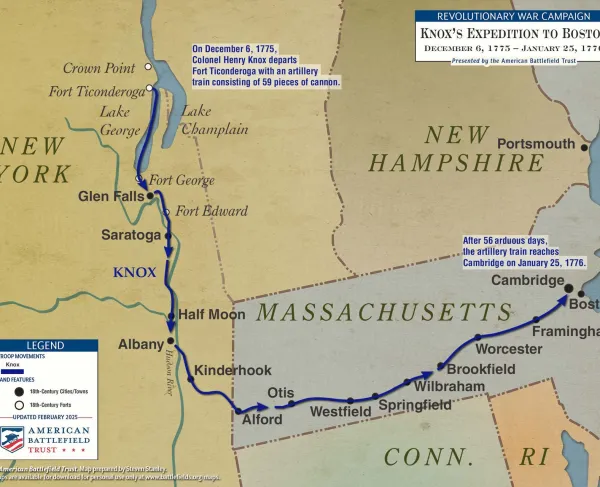

Henry Knox and his train of artillery trekked from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston in a brutal winter, that much everyone agrees on. But what happened to the cannons? Most scholars say that Knox didn’t lose a single piece of artillery on the way south, which is a remarkable feat on top of the unlikely journey itself. Letters from Knox to George Washington outline the inventory of artillery he decided to transport, including a total of 60 cannons, mortars and howitzers. Between centuries-old rumors, cannons found on riverbeds and the question of where the weapons went after the British scattered from Boston, there’s more than meets the eye to this story that’s already fit for an action movie.

There’s one issue with the claim that every cannon made it to Boston — the British six-pound cannon with the cypher of King George III found at the bottom of the Mohawk River. The iron cannon was recovered around 1853, near a crossing point that Henry Knox’s Noble Train of Artillery is understood to have taken. We know from Knox’s journal and letters that multiple cannons broke through the ice on the long journey, but he wrote that all were recovered. It’s possible that one slipped away, but a cannon is hard to misplace. The recovered artillery bears the cypher of King George III, who ruled from 1760 to 1820, which supports the idea that it was, at one point, at Fort Ticonderoga when it was controlled by the British. But the Revolution saw years of battles near the Hudson River Valley, so other explanations are possible as well.

The legacy of the “lost” cannon wasn’t confined to its possible loss from the Noble Train of Artillery but continued well into the 20th century. After it was recovered, it was taken to Cohoes, New York, where it became a political symbol when a local political party began firing it to celebrate its victories. When the opposing party came into power, the cannon was pushed back into the Mohawk River, either by the original party in protest or by the opposition in an act of triumph. It remained in the river until 1907, when the city historian of Cohoes had it removed and displayed. If being thrown into the river twice weren’t enough, the cannon was donated to become scrap metal when America entered World War II in 1941. Fortunately, the staff at Fort Ticonderoga learned of its fate and tracked down the doomed cannon with help from the community. They found it in a scrap yard, smashed to pieces. The cannon was welded back together from the few remaining fragments, new supports were cast, and the gun was returned to Ticonderoga, where it resides to this day.

The sunken cannon isn’t the only piece of lore from Cohoes, though: There are centuries-old rumors of buried treasure in a brass cannon off the Mohawk River. The story goes that the Continental Army hid the gold to prevent it from falling into British hands while retreating. While it’s true that Knox’s train passed by and General Philip Schuyler had his troops in fortifications on the Mohawk in the 1777 Saratoga Campaign, the buried artillery and accompanying riches have yet to be discovered.

After the Americans retook Boston, General Washington ordered Knox to take all available artillery to the New York City area to prepare for the next conflict, which he did successfully. Knox moved 121 cannons, ranging in size from three-pounders to 32-pounders, to batteries and redoubts around the city. It was most likely a much simpler endeavor without the bitter winter, as Knox reported to Washington in a letter on June 10, 1776, that the cannons were “mounted and fit for action.”

Henry Knox continued rising through the ranks as a leader, thanks to his military genius, and became the youngest major general in the army on March 22, 1782. This came after a wildly successful Siege of Yorktown, with Knox directing artillery, and his creation of the first artillery training camp in the Continental Army. His understanding of troop leadership and the art of logistics is woven throughout victories in the American Revolution, but no feat was greater than dragging nearly 60 tons of artillery through that snowy New York winter in 1775.