Battlements at Citadelle of Quebec facing the Plains of Abraham have been mounted with cannon — today, late 19th–century examples — for nearly 400 years.

The invasion of Canada, or at least of the St. Lawrence River Valley, was the first major campaign of the American Revolution. Though ultimately a failure, its consequences would help pave the way for the 13 colonies to secure their independence in 1783. It also marked the last time the city of Québec was besieged by a foreign army — a poignant reminder of the heavy toll war exacts on civilian populations. From Colonel Benedict Arnold’s daring expedition to General Richard Montgomery’s capture of Fort Saint-Jean and Montréal, the siege and battle on the last freezing night of the year to General John Thomas’s fateful retreat, these events played a crucial role in shaping the city’s and conflict’s trajectory and eventual outcome.

Reaching Québec: Montgomery’s Invasion and Arnold’s Expedition

The Continental Army was officially formed on June 14, 1775, and the Second Continental Congress swiftly appointed George Washington commander in chief. While Washington focused on unifying the forces besieging Boston, Major General Philip Schuyler, commander of the Northern Department, was tasked with evaluating the feasibility of an invasion of Canada, if deemed necessary.

The Province of Québec — established by the British in 1763 following their victory in the French and Indian War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris — was viewed as both a strategic threat and a potential opportunity. If the French-speaking population could be persuaded to join the rebellion, it would sever a vital British link in North America and remove the possibility of invasion of the colonies from the north. In future negotiations with the Crown, the captured Province of Québec would also provide leverage.

In July and August 1775, Schuyler began assembling troops and planning the main invasion route via Lake Champlain. Local support and the neutrality of First Nations were deemed essential to success. However, Schuyler’s initial assault on Fort Saint-Jean in early September failed, and illness forced him to withdraw. Command then passed to General Richard Montgomery.

Despite facing smallpox outbreaks and inadequate artillery, Montgomery pressed on. After a prolonged siege, his forces captured Fort Saint-Jean, a key defensive position south of Montréal, on November 3, 1775. This victory led directly to the capture of Montréal on November 13. With the city secured, Montgomery set sights on Québec City.

Meanwhile, a second operation was underway, as Colonel Benedict Arnold launched a covert expedition through the wilderness of northern Massachusetts (present-day Maine), up the Kennebec River and down the Chaudière River into Québec. They faced a logistical nightmare plagued by inaccurate maps and insufficient supplies, as well as harsh weather. The force that reached the heights overlooking Québec City on November 14 was half its original strength. At the French settlements they encountered along the way, some locals offered food and limited support, but hopes of a widespread uprising proved unfounded. The challenge of capturing Québec loomed large.

Preparing for the Unavoidable: Québec City Braces for Attack

As the Continental Army advanced, British authorities were fully aware of the threat and began preparing for a siege. Governor General Guy Carleton spent the summer in Montréal, overseeing its defense, while Lieutenant-Governor Hector-Théophilus Cramahé remained in Québec City. Though both men now held civilian posts, they were veterans of the Siege of Québec (1759–1760), when Britain had captured New France.

In late summer 1775, Cramahé mobilized the militia to reinforce the city’s fortifications. On September 16, the British began regulating movement in and out of the city — every new arrival was required to identify themselves to the city guards. By September 28, navigation on the St. Lawrence River near the city was restricted to essential vessels. Québec was on high alert.

Throughout October, Cramahé worked to prepare the city and its defenders for a potential winter siege. Reinforcements arrived in early November: Lieutenant-Colonel Allan Maclean, commanding the Royal Highland Emigrants — composed largely of veterans from the 78th Regiment, who fought in the French and Indian War— reached Québec on November 10. His arrival was a turning point: Maclean assumed command of military operations, providing a much-needed boost to morale just days before Colonel Arnold’s force appeared outside the city.

On November 22, Carleton issued a final ultimatum to the city’s inhabitants: All men of fighting age must either take up arms or evacuate. He also ordered the construction of palisades in the Lower Town by the militia and British troops. Finally, Québec was ready to stand strong against the invasion.

December 1775: At Your Post

Although Arnold’s force reached the outskirts of Québec City by mid-November, they were only able to secure a few houses for shelter and received limited care from the nuns at the General Hospital, north of the city. Arnold knew he had to wait for Montgomery, whose larger force was coming from Montréal with vital resources.

On December 3, the two detachments finally united outside Québec. Montgomery brought much-needed supplies, including food and winter clothing, a welcome reprieve for Arnold’s weary troops. The following day, the combined Continental force — approximately 1,200 men — returned to the Plains of Abraham to demand the city’s surrender. They were refused.

In the days that followed, Arnold, Montgomery and their senior officers began planning an assault. They understood that a conventional siege was impossible: Québec’s garrison numbered around 1,800, including British regulars, sailors and Canadian militiamen determined to defend their homes. With limited manpower and ammunition, the Continental Army’s only chance lay in a swift, decisive attack. A snowstorm would also bring additional cover and could create some confusion for the defenders. The Continental Army decided to wait for such a storm to launch the attack.

Time was running out. Many of Montgomery’s soldiers had enlisted for one year, with their service ending on December 31. Additionally, smallpox — already present in the city — was spreading among the Continental troops, probably transmitted by a limited number of sympathizers who had left Québec to join the invaders.

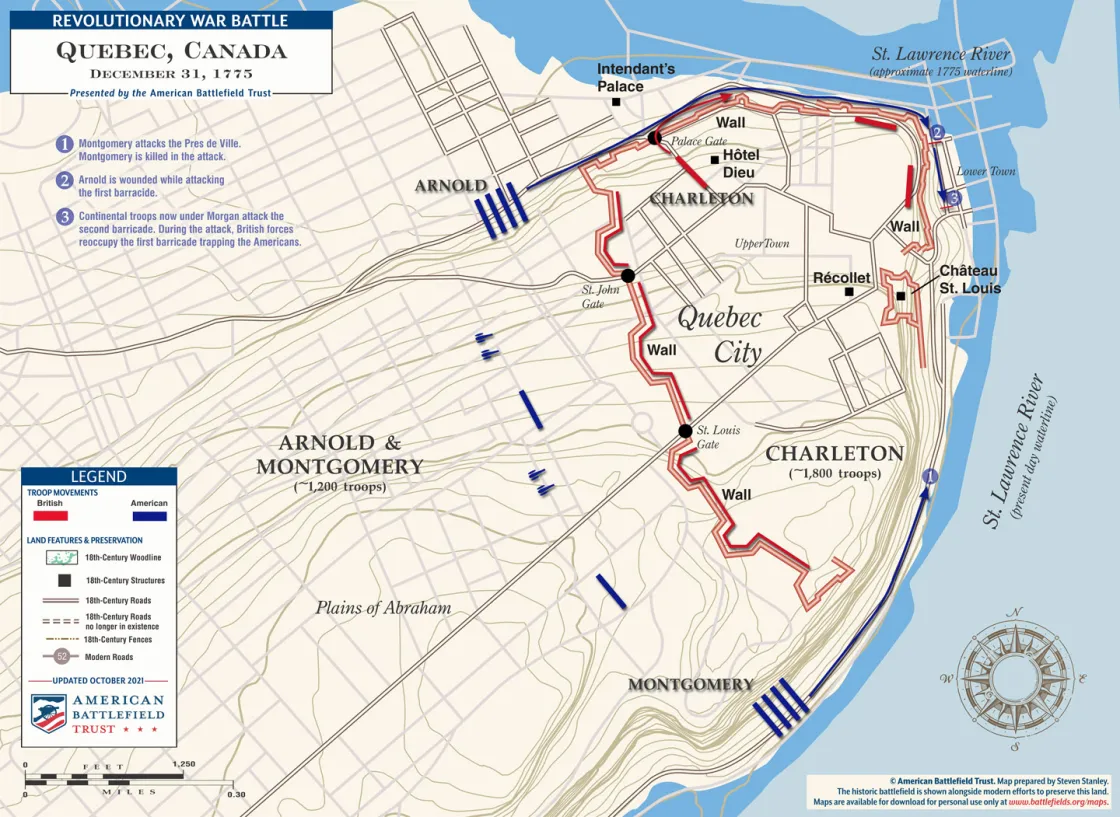

The plan was bold: Unable to breach the city’s fortifications from the Plains of Abraham, the Continental Army would launch a two-pronged assault on the Lower Town, attacking simultaneously from the north and south. The goal was to converge near Place Royale, ascend the narrow road leading to the Governor’s Palace overlooking the St. Lawrence River and force a British surrender.

Success would require every available soldier, favorable weather conditions and a measure of luck.

The Battle

On December 31, as the long-awaited snowstorm raged over the city, the time had come.

The attack began before sunrise, with Captain Jacob Brown leading a force of approximately 160 militiamen in an assault on the Cape Diamond Redoubt, located on the southern edge of the cliff near the St. Lawrence River. Just before 5:00 a.m., Brown launched flares to signal the start of the operation and opened fire on the redoubt. This was part of a coordinated feint, which also included James Livingston’s First Canadian Regiment. This detachment of 200 men was tasked with creating a second diversion by attacking Saint-Jean Gate on the western fortifications. With these distractions in place, the main assault could proceed.

General Montgomery descended from the Plains of Abraham, leading nearly 400 men down a narrow path along the cliffside toward the westernmost edge of of the Lower Town. The first barricade was taken with little resistance. Montgomery, at the head of a vanguard of about 50 men, pressed forward through a second barricade and saw what he believed to be an opportunity. He advanced toward a large two-story building, unaware that it was a barracks manned by defenders armed with muskets and artillery.

As the Continental troops approached, the British and Canadian defenders opened fire at close range. Montgomery and several senior officers were killed instantly. Colonel Donald Campbell, now the highest-ranking officer in the southern detachment, saw no viable path forward and ordered a retreat to the Plains of Abraham — leaving Montgomery’s body and the fallen vanguard behind. The southern assault was a complete failure.

Simultaneously, Colonel Arnold led his detachment from the north. He descended from the heights of Saint-Roch, staying close to the cliffs to take advantage of their cover. Progress was slow but steady until the force encountered heavy fire near Porte du Palais (Palace Gate). The defenders’ volleys confirmed to Governor Carleton that the attacks from the Plains of Abraham were diversions, prompting British and Canadian forces to regroup and reinforce the northern defenses.

At a disadvantage due to the elevation and narrow streets, Arnold pressed forward to shield his men from enemy fire. The blizzard added confusion and disorientation. As Arnold prepared to assault the first barricade, he was struck in the leg by a musket ball and had to withdraw. Command passed to Captain Daniel Morgan.

Morgan led a successful frontal assault on the barricade, personally leading the charge and overpowering the defenders. With the path ahead temporarily clear, Morgan advanced deeper into the city. However, the snowstorm dampened the soldiers’ gunpowder, and the narrow streets made maneuvering difficult. Morgan was forced to pause for half an hour to allow the rear guard to catch up.

By the time Captain Henry Dearborn led the rear guard past the first barricade, British and Canadian forces had regrouped. Dearborn’s men were intercepted and forced to surrender. Morgan, now isolated, attempted to breach a second barricade but was blocked by a 12-foot palisade. Behind him, more than 500 Royal Highland Emigrants and British sailors had cut off any retreat.

Trapped in the snow-covered streets of Québec, Morgan had no choice. Before 10:00 a.m., he surrendered. Québec City had withstood the assault.

The Aftermath

The defenders’ morale was strengthened by their victory. Of the 431 Continental soldiers captured by the British, most were confined in the Seminary under harsh conditions. Smallpox continued to spread, and the cold Québec winter made the rooms frigid and inhospitable. The situation was so dire that some prisoners attempted to escape but were quickly apprehended. The ringleaders were transferred to ships anchored in front of the city, where they were used as human shields against gun batteries the Continental Army had begun installing on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in early spring 1776.

Unable to organize a proper retreat due to heavy snow — and perhaps still hopeful that the new year would bring a reversal of fortune — Arnold attempted to maintain a siege. However, he failed to make any significant impact on the city’s formidable defenses. In response to the deteriorating situation, Continental Army leadership dispatched General John Thomas to assume command and oversee a withdrawal from the Province of Québec.

Thomas arrived in Québec on May 1, 1776, and quickly assessed the dire state of affairs: a rampant smallpox outbreak, demoralized troops and no realistic path to victory. He ordered the lifting of the siege and a full retreat. Thomas himself contracted smallpox during the withdrawal and died in early June 1776 along the Richelieu River.

Throughout the campaign, the hope that the French-speaking population would rise in support of the Continental Army never materialized. While some Canadiens were eager to retaliate against the British conquerors of 1759, an equal number took up arms in defense of their homes. A third group remained largely neutral. In the end, both the British and the Continental Congress misjudged the loyalties of the Canadien population.

Though the invasion was a tactical failure, its long-term consequences proved advantageous for the colonies. In the fall of 1776, the British pushed the Continental Army southward along Lake Champlain after the Battle of Valcour Island. Yet Benedict Arnold, commanding from Fort Ticonderoga, managed to delay further British advances, buying precious time for the Continental forces to regroup and prepare for the following year’s campaign.

This delay would prove critical during the Battles of Saratoga in 1777, where the Continental Army forced a British surrender and secured French support for the war effort. Despite occasional consideration, the Continental Army never launched another invasion of the Province of Québec.

Related Battles

515

18