Icy Resolve, Icy Determination

Ticonderoga, N.Y.

In the tense weeks after Lexington and Concord, General Thomas Gage and the British Army found themselves in an unenviable position. Hemmed in on the Boston Peninsula by more than 10,000 Provincial militia, the Redcoats had lost access to the fertile interior of Massachusetts. Only the Royal Navy’s control of the harbor kept Gage’s troops from starvation. Thousands of civilians, many loyal to the Crown, also crowded into Boston, dependent on the British military for food and fuel.

The army surrounding Boston faced difficulties of its own. Farmers turned militiamen could feed themselves, but their supply of muskets, powder and shot was meager. Each week away from their fields threatened their families’ survival. Though they had the British bottled up, they lacked the means to strike a decisive blow.

That uneasy stalemate erupted on June 17, 1775, at the Battle of Bunker Hill. There, the Provincials proved both their courage and their limitations. They stood toe to toe with Britain’s best soldiers, but their powder ran low and their ranks lacked coordination. The war would require more than bravery: It needed discipline, leadership and, critically, artillery.

Relief arrived on July 3, when George Washington took command of the newly christened Continental Army. A veteran of the French and Indian War, Washington set about imposing order and purpose upon a force of volunteers. As he toured the siege lines that summer, he stopped at Roxbury, where a formidable fortification guarded the only land approach to Boston. The works impressed him, but the engineer behind them impressed him even more — a self-taught, 25-year-old bookseller named Henry Knox.

Washington recognized in Knox the rare combination of ingenuity and resolve the army desperately needed. Years later, after the Siege of Yorktown, Washington would say of Knox, “The Resources of His Genius Supplied the Deficit of Means.” That insight was born from watching Knox succeed in many difficult situations, particularly his first military enterprise. News had reached Cambridge that Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold had captured the British fortress at Ticonderoga, which held the heavy artillery Washington lacked. If those guns could be brought to Boston, they might break the stalemate.

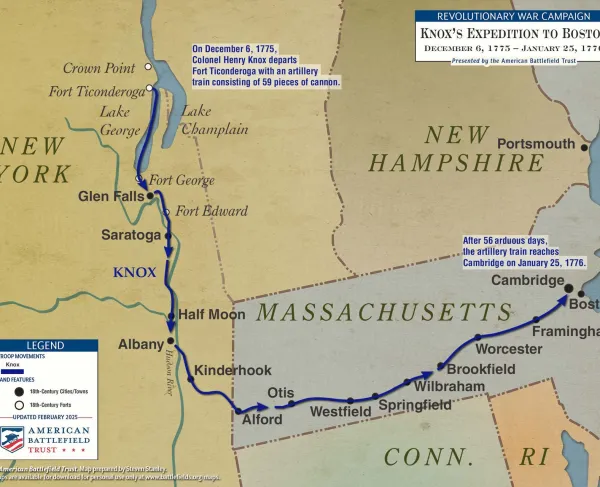

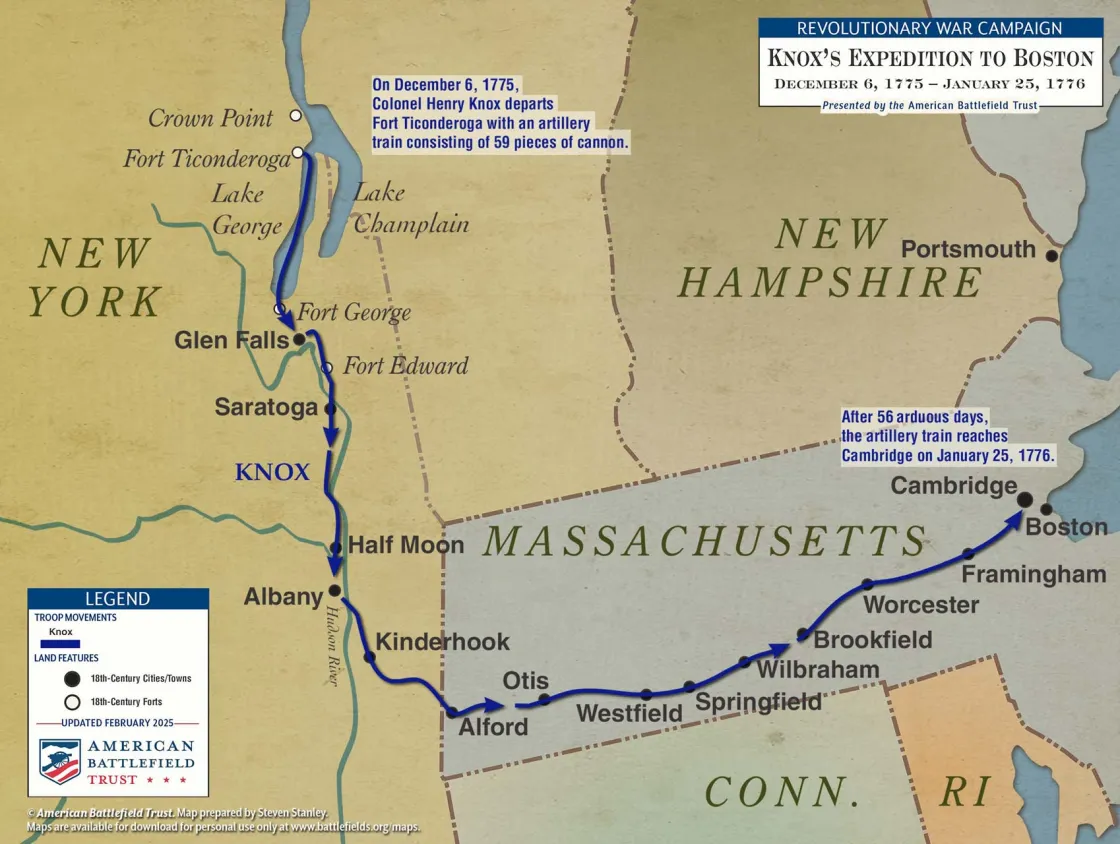

In November, Washington entrusted Knox with that mission. He was to travel to New York City to secure powder and shot, then continue north to Fort Ticonderoga and bring back the best of the captured artillery — more than 60 tons in all. Washington wrote to General Philip Schuyler, warning that he was “in very great want of Powder, Lead, Mortars, Cannon, indeed of most Sorts of Military Stores,” and urging him to assist Knox by every means possible.

Knox’s journey was grueling from the outset. The ride from Cambridge to New York and on to Ticonderoga covered more than 600 miles of cold and frozen roads. Leaving on November 17, Knox and his brother William reached the old fort by December 5, 1775. They immediately began selecting guns for transport, moving the chosen pieces down to the La Chute River, the link between Lake Champlain and Lake George. Here they faced their first major obstacle.

Lake George stretched 32 miles through steep, snow-covered hills. As with most colonial travel, movement by water was always easier than movement by road, especially for heavy cannons. Knox assembled a flotilla of bateaux and scows, and a curious canoe-like sailing vessel called a pettiauger, loaded them with cannon, and set out on December 6. Snow swept up from the south, forcing the men to row against the wind through freezing spray and forming ice. That night, they took shelter with a Mohawk community at Sabbath Day Point, only to learn that one of the boats — commanded by Knox’s brother — had struck a rock and sunk. The men raised and repaired it, but it went down again shortly after.

Nine days later, battered and frostbitten, Knox’s fleet reached the southern end of the lake. From Fort George, he dispatched a rider to George Palmer of Stillwater, New York, who had agreed to supply teams and sleds. But Palmer, wary of the cost, canceled the contract and ordered new arrangements. His cousin Harmanus Schuyler procured fresh teams and had holes cut in the ice of the Hudson River so that upwelling water would refreeze and strengthen the crossings in advance of the expected tons of metal, wood and animal that would need the strength of deep ice to safely cross.

By early January 1776, the “Noble Train of Artillery” was on the move. Deep snow blanketed the upper Hudson Valley, aiding the sleds’ progress. One by one, the massive guns creaked over frozen stretches of the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers, past the future battle sites at Saratoga, through the ancient town of Albany, up forested slopes and across the icy ridges of the Berkshires. The journey was perilous — sleds occasionally broke through the ice, and drivers had to cut their teams loose to avoid being dragged under — but the column pressed on.

In the hill towns of western Massachusetts, the sight of Knox’s caravan stirred wonder. At Westfield, residents greeted the exhausted men as heroes and begged Knox to fire one of his mortars. The train carried no powder with it, but the people of Westfield supplied the needed munition and the gun’s thunder echoed for miles — a triumphant prelude to liberation.

By mid-January, Knox reached Springfield, where he paid and dismissed his New York drivers and hired new teams to carry the cannon the remaining 70 miles. On January 18, he and the first ox-drawn sleds rumbled into Framingham, Massachusetts, ending one of the most astonishing logistical feats of the Revolution. Knox established an artillery park there before riding to the Continental Army’s headquarters at Cambridge to report to Washington, who swiftly commissioned him as Colonel of the Continental Artillery and convened a Council of War to plan the guns’ deployment.

In Framingham, the “Noble Train” became a sensation. Townspeople came to marvel at the cannon that had crossed mountains and frozen lakes. Among the curious visitors were John Adams and Elbridge Gerry, en route to the Continental Congress, eager to witness the triumph of the young bookseller they knew and esteemed.

The decisive moment came on the night of March 4. As British forces were distracted by bombardment from Cobble Hill and Lechmere Point, Continental troops under General John Thomas hauled prefabricated fortifications and Knox’s guns up Dorchester Heights. By dawn, Washington’s army commanded the harbor. When General William Howe surveyed the scene through his spyglass, he reportedly exclaimed, “Good God! These fellows have done more work in one night than I could have made my army do in three months!”

A storm prevented Howe’s planned counterattack, and within days he resolved to evacuate. On March 17, more than a 100 ships carrying 11,000 British soldiers, officers, Loyalists and camp followers set sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia. They left behind a scarred, half-empty city ravaged by siege and smallpox and handed the Americans their first major victory of the war.

The Continental Congress ordered a gold medal for Washington, honoring the triumph that freed Boston. Yet Washington’s greatest reward lay in the men who achieved it — none more so than Henry Knox. The young artilleryman had turned vision into reality, proving that ingenuity and determination could supply the “deficit of means” in America’s fight for liberty.

Of the 60 artillery Knox brought to Boston, most continued in service, some later recaptured at Ticonderoga. They did not remain as a single unit, but elements of the train saw action in many of the war’s major campaigns — New York, the Ten Crucial Days, Philadelphia, Saratoga and beyond. Today, only one fragment within museum collections — part of a 13-inch mortar — can be definitively traced to his epic trek; it rests today at Fort Ticonderoga. But Knox’s real monument endures in the nation his courage helped to secure, and in the enduring image of a man who transformed learning into leadership and determination into destiny.

Related Battles

19

79