On June 17, 1775, as British redcoats marched up the heights of Bunker Hill outside of Boston, Massachusetts, they were met with a hail of musketry from the defenders of the earthen redoubt. The defenders were a motley collection of colonists, from various New England colonies. Included in their ranks of 2,400 were approximately 120 Black militiamen, including Peter Salem. Peter Salem was a freed slave from Massachusetts who is known for mortally wounding British Major John Pitcairn during the fighting at Bunker Hill. Colonel William Prescott's militia held their own until ammunition ran low, repulsing the British from Bunker Hill.

The main military force, which coalesced under General George Washington as the Continental Army, was not an integrated army until 1776. In November of 1775, Washington barred the enlistment of free Blacks and slaves. Within two months, however, Washington reversed this decision, and despite many attempts to block Blacks from serving their country, hundreds of Blacks enlisted nonetheless. Many Blacks who fought and were enslaved fought for their freedom and independence as a person of color. After the war, many Blacks gave their pensions and enlistment bounties to their former masters as a payment for their freedom. Cuffee Wells is just one example. Wells was a surgeon in the Continental Army and after his service in the Revolution, he paid his enlistment bounty to his former master and lived the rest of his life as a free man in Lebanon, Connecticut. The integrated army in the Revolution was the last integrated American army until the Korean War nearly 175 years later in 1950. Standing shoulder to shoulder, an ethnically diverse soldiery formed. From free and enslaved Blacks, to Native Americans, native born colonists, to foreign recruits, Washington's integrated army was a diverse and unique fighting force for a long and grueling eight-year war.

One of the most famous units was the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. The Rhode Island Assembly decreed on February 14, 1778, to allow, “every able-bodied negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave in this state to enlist into the two Battalions to serve the during the Continuance of the present War with Great-Britain...” Even more striking was the following clause, “every slave, so enlisting, shall upon his passing muster before Col. Christopher Greene, be immediately discharged from the service of his master or mistress; and be absolutely FREE, as though he had never been encumbered with any Kind of Servitude or Slavery.” Although this last clause was repealed within four months due to the outcry of Rhode Island slave owners, more than 100 free and formerly enslaved Rhode Island African Americans had enlisted in the Continental cause to fight for their own independence.

Recruited throughout the spring of 1778, the regiment's companies comprised Black and white soldiers, along with Native Americans. It is estimated that less than 200 African Americans served in the unit during the conflict. The 1st Rhode Island, which was first created in 1775, saw action straight through the war, fighting at the Siege of Boston, the New York and New Jersey Campaign, Battle of Red Bank, the Battle of Rhode Island, and the Siege of Yorktown. In February 1781, the unit merged with the 2nd Rhode Island.

Also serving in various theaters of operations were Native American troops. While encamped at Valley Forge, General Washington asked for a delegation of Oneida and Tuscarora warriors sent to his army. His aim was to use them as scouts to gather intelligence, harass British patrols, and to confiscate supplies that could be of use to the main army. Washington wrote to fellow Continental general Philip Schuyler that “The Oneidas and Tuscaroras have a particular claim to attention and kindness, for their perseverance and fidelity.” These warriors arrived at Valley Forge on May 15, 1778.

Just four days later, on May 19, 1778, Oneida Native Americans, joined with Daniel Morgan’s Virginia riflemen to spearhead the first movement of Washington’s army from Valley Forge. During the action at Barren Hill, Oneida soldiers helped delay the advancing British force. The six Oneida soldiers that died that day in the action of Barren Hill are buried in a single plot in Saint Peter Evangelical Lutheran Church Cemetery in Lafayette Hill, Pennsylvania, named in honor of the French general in command of American forces that day, the Marquis de Lafayette. The warriors of these two tribes were among the last of Lafayette’s forces to retreat across the Schuylkill River that day.

With the return of the Continental army to the outskirts of New York City following the Battle of Monmouth Court House in June, muster rolls of the army were taken in White Plains, New York, in August 1778. Included on those returns were the names of at least 755 Blacks serving in the ranks. Not only were they serving in units from the northern colonies, but 58 African Americans had mustered into the North Carolina Line. Their roles in Washington’s army included pioneer duties, such as constructing fortifications and clearing roads to musicians, guides, spies, and rank-and-file infantrymen. One of the men, Jonathan Overton, served in the North Carolina Continentals and lived to be 101, dying in 1849. The Edenton Whig, a local newspaper, described Overton as, “a soldier of the Revolution,” and, “served under Washington and was at the battle of Yorktown,” Overton was praised by the community and say that, "He has lived among us longer than the ordinary period allotted to human life, and always sustained a character for honesty, industry, and integrity. It is not always that the eulogies or epitaphs of persons, in much more exalted positions than his, contain much truth as does this brief tribute to the humble and patriotic negro."

Even in Washington’s home of Virginia, Black soldiers fought in Virginia units. During the 1781 campaign against British General Lord Charles Cornwallis, there are five Black veteran pension records showing service under the Marquis de Lafayette in the Virginia Battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gaskin. When the French army of General Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau headed toward Yorktown in the summer of 1781, one of the commanding officer’s aides, Baron von Closen left the following observation: “A quarter of them [the Continental Army] are Negroes, merry, confident, and sturdy.” These African Americans received the same pay as their fellow white soldiers but did not see the type of military promotions as their counterparts. There is no record of an African American serving higher than the rank of corporal in the main army. Yet, they were present at every engagement and shivered through every winter.

An integrated military force representing the colonies was not exclusive to Washington’s main army. There were Blacks serving in the reconstituted 1st and 2nd Virginia units that fought with General Nathanael Greene at the Battle of Guilford Court House. There is also the record from the British of a prisoner of war, George with the word “Negro” written beside his name. He had served in Greene’s third line of defense with the 2nd Maryland Regiment. Thomas Gibson, a free man of color from Guilford County, enlisted for two years’ service in 1781 and defended his home county that March.

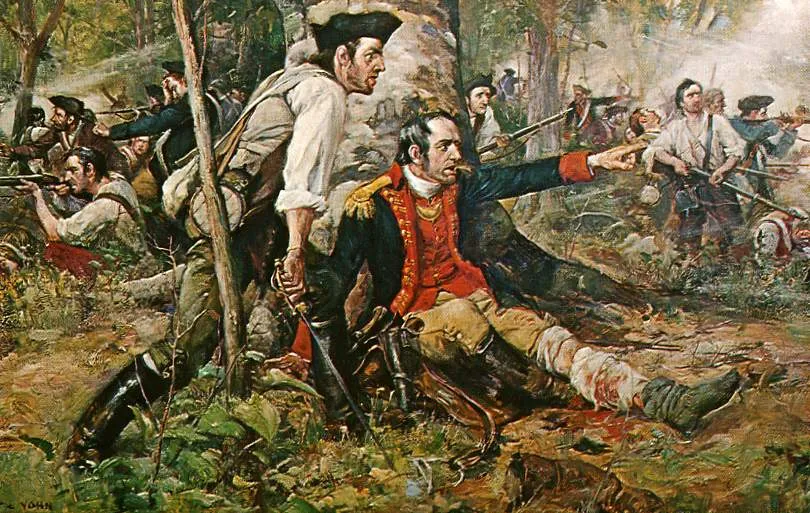

Throughout the Revolution, the fight for independence permeated into Native American tribes and alliances. The largest conglomeration of tribes, the Iroquois Confederacy, split along regional lines. The tribes closest to the American settlements along the eastern seaboard sided with the Patriots. During the larger Saratoga Campaign, when British and their Native American allies were besieging Fort Stanwix in upper New York State, a pro-patriot militia column under the command of Nicholas Herkimer marched to the patriot's relief. Herkimer's militia, which consisted of 60-100 Native Americans from the Oneida tribe, were ambushed by the Seneca and Mohawk tribes in alliance with the British at the Battle of Oriskany. One of the casualties that day was Herkimer who was mortally wounded but kept command by being propped against a tree.

Another Native American tribe, the Catawba, assisted South Carolina militia commander, Colonel Thomas Sumter during the Second Battle of Hanging Rock on August 6, 1780. There were 35 warriors as part of the force, led by Generals New River, a Catwaba leader, and Billy Ayers along with Major Jacob Ayers. The Catawba had taken part in an earlier raid against a British position with Sumter as well.

The American Revolution's success was hard-fought by a diverse group of people. The American Revolution is marked with a varying cast of diverse soldiers who fought for their independence. Under the command of General George Washington and many other generals, the integrated army that served in the Revolution was a unique fighting force that catalyzed the formation of the Republic. While the contributions and sacrifices of these individuals are not as well known, their significance to the new government's creation is critical.

Further Reading:

- The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities (Studies in North American Indian History) By:Colin G. Calloway

- Black Patriots and Loyalists By: Alan Gilbert

- Race and Revolution By: Gary B. Nash

- Native Americans in the American Revolution: How the War Divided, Devastated, and Transformed the Early American Indian World By: Ethan A. Schmidt

Related Battles

450

1,054

465

28

330

1,135

325

381

217

233

389

8,589