The capture of the Confederate river fortress at Vicksburg, Mississippi on July 4, 1863 was a major turning point of the Civil War. Please consider these facts in order to expand your appreciation of this dramatic campaign.

Fact #1: Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis both saw Vicksburg as “the key” to the Confederacy.

By the summer of 1863, Union advances from the Memphis in the North and New Orleans in the South had constricted Confederate control of the Mississippi River to a small section stretching from Port Hudson, Louisiana to the fortified city of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Early in the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln, gesturing to a map of the region, declared to his military advisors that "Vicksburg is the key" and that the failure to capture this city meant "hog and hominy without limit, fresh troops from all the states of the far South [for the Confederacy]." For not only would the capture of Vicksburg benefit the commercial interests and military operations of the Union, but Vicksburg was also a vital logistical link to the resource-rich Trans-Mississippi. It was here at Vicksburg that huge quantities of molasses, cane sugar, sheep, oxen, cattle, mules, sweet potatoes, butter, wool, and salt, were transported across the great river and onto every corner of the Confederacy. Some historians have argued that it was the Trans-Mississippi, not the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia that was the true breadbasket of the Confederacy. And it was via Vicksburg that important war material and arms smuggled through Mexican ports could defy the Federal blockade and sustain the military needs of the South.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis, whose plantation home was just south of Vicksburg, clearly recognized why the city was worth defending. For Vicksburg, in his words, was "the nailhead that held the South’s two halves together."

Fact #2: Ulysses S. Grant captured Vicksburg by moving away from it.

After bloody repulses in the last months of 1862, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, commanding the Union Army of the Tennessee, determines to push his army south through Louisiana, using the Mississippi River to supply his troops. His plan is to land his army below Vicksburg, taking this Confederate bastion from the South. On April 16 and 22, 1863, Admiral David D. Porter's fleet successfully runs past the Vicksburg batteries, giving Grant the naval power necessary to cross the Mississippi, which he does on April 29, 1863. The following day, the Federals establish a strong lodgment east of the river after the Battle of Port Gibson.

On the east bank, Grant's swiftly moving troops flank the Confederate garrison at Grand Gulf, forcing the Rebels to abandon the river fortress and make a beeline for Vicksburg. Grant, however, realizes that the terrain before him—broken by creeks and steep-sloped ravines—is well-suited for defense; his opponent will be able to contest nearly every foot of ground. Furthermore, Grant's front will be constricted by the Mississippi River to his right and the Big Black River to his left, preventing him from using his superiority in numbers to overwhelm the Confederates. In the meantime, the Southern Railroad will provide the Rebels supplies, and—even worse—reinforcements. If he is going to take Vicksburg, Grant must first cut the railroad. On May 6, the Army of the Tennessee marches northeast, away from Vicksburg, toward the Southern Railroad. While en route, the Seventeenth Corps, under Gen. James B. McPherson, encounters Confederates outside of Raymond, Mississippi. This is the vanguard of a relief force under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, bound for Vicksburg. To counter this threat to his rear, Grant sends McPherson and the Fifteenth Corps under Gen. William T. Sherman toward the Mississippi State capitol of Jackson. After a brief battle, Johnston seemingly abandons his plans to relieve Pemberton and withdraws, never again to play an active role in the Vicksburg campaign. With the Southern Railroad now squarely in Union hands, and the threat to his rear neutralized, Grant can turn to his sights on Vicksburg.

Fact #3: Confederate leaders were divided on strategy at Vicksburg.

Gen. John C. Pemberton, commanding the Confederate Army of Mississippi at Vicksburg, was in a tough bind. On the one hand, his immediate superior, Joe Johnston, placed little stock in defending Vicksburg and instead preferred to have Pemberton's force link up with his own. Together, Johnston reasoned, the Confederate armies could defeat Grant's troops in the open field before shifting their forces to other imperiled points of the Confederacy. On the other hand, Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president, consistently directed Pemberton to protect Vicksburg at all hazards.

The Philadelphia-born Pemberton was keenly aware that abandoning Vicksburg might be viewed as an act of treason. He'd faced similar criticism in 1862 when he advocated the withdrawal from Charleston—much to the chagrin of South Carolina's governor. What's more, a directive from the President of the Confederacy was not something he could simply ignore. Nevertheless, Pemberton attempted to mollify his commanding officer. He moved his troops out of the Vicksburg trenches in the direction of Grant's army hoping to engage—and possibly defeat—the Yankees outside of Vicksburg, and thereby protect the city. Pemberton's movements, however, were slow and he made little effort to coordinate with Johnston. This half-hearted attempt to please both his military and civilian superiors placed Pemberton's army in a precarious position that the Federals would soon exploit.

Fact #4: The decisive battle for Vicksburg was fought at Champion Hill, Mississippi.

While groping through the countryside in search of Grant's army, word reached Pemberton that a portion of his opponent's supply train was lightly defended and within easy reach of his Confederate force. Late on the morning of May 15, 1863, Pemberton leisurely moves his army toward the target. Recent rains, however, have destroyed a bridge over Bakers Creek, forcing Pemberton to make a lengthy detour to cross the stream. When night falls on the 15th the Confederate army is badly spread out on narrow roads, with Bakers Creek to its rear.

In the mean time, Grant has acted swiftly. His three corps are moving west toward Vicksburg on three parallel axes. Pemberton's attenuated line lies directly across the path of the Federal juggernaut. At 7:30 am on May 16th, the head of Grant's southernmost column runs into Pemberton's right flank. At the same time, his two remaining columns are threatening the Confederate left flank near Champion Hill. The two sides vie for control of the hill for several bloody hours before the Federals' superiority in numbers compel the Confederates to withdraw. Only the skill of his junior officers and the bravery of his men save Pemberton from complete disaster, buying time for engineers to build a bridge over Bakers creek and allowing the bulk of Pemberton's army to escape intact. But the Confederates will never again have the chance to defeat the Union troops in the open field. Retreat to the trenches at Vicksburg is Pemberton's only option.

Fact #5: Ulysses S. Grant tried to take Vicksburg by storm twice before settling in to a siege.

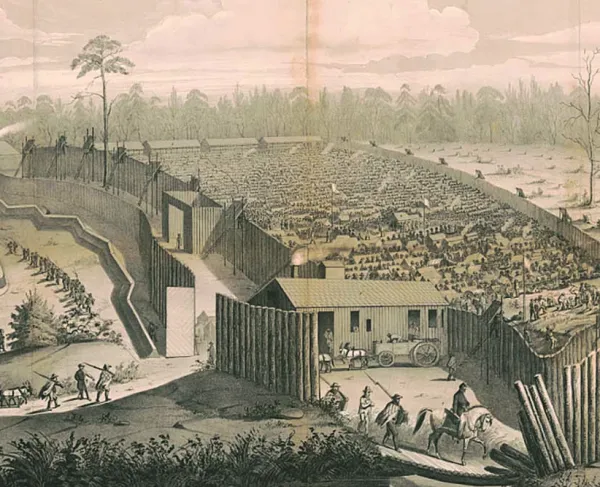

The Confederate army marched into Vicksburg on May 17, 1863, with Grant’s Federals hot on their heels. Seeing an opportunity to strike while his opponent was disorganized, Grant ordered a small-scale assault on three axes, the Graveyard Road, the Jackson Road, and the Southern Railroad on May 19. Despite planting their colors on the Rebel works, the Yankee attackers were turned back with substantial loss.

On May 22, Grant tried again. After a massive bombardment, each of his three corps commanders—James McPherson, John McClernand, and Sherman—were ordered to attack in their respective sectors. On the right, Sherman's Fifteenth Corps' assault was torn to pieces as it advanced up the narrow defiles approaching the Stockade Redan. In the center, McPherson’s men were devastated by cross-fire and turned back after finding that their siege ladders were too short to scale the fortifications. McClernand’s men on the left were closest to breaking the Confederate line, with three regiments planting their colors on the Railroad Redan. McClernand sent back to Grant for additional help. A diversion by McPherson or Sherman, McClernand believed, would afford him the opportunity to complete the breakthrough. Grant, however, was slow to respond to his subordinate's call for aid. McPherson sends a division to McClernand, but it is too little too late--the Confederates in this sector rally and drive McClernand back. At the same time, Sherman throws more of his men at the Stockade Redan and is again repulsed.

A combination of determined defense and command confusion led to another morale-sapping defeat for the Union forces. All told, Grant lost more than 4,000 men in the May offensive. The Confederates lost less than 600. Although the Union army had won a string of victories in the open field, the Vicksburg defenses proved impervious to hasty attacks. The May offensive convinced Grant to lay siege to the city and starve the Confederates out.

Fact #6: Union naval operations were essential to the success of Grant’s infantry.

When David Dixon Porter was appointed to lead the Mississippi River Squadron, the naval detachment co-operating with Grant near Vicksburg, he was thrust into a command that far exceeded any he had held before, both in tonnage of ships and in importance of victory. Porter was a man of courage and skill, but he came to Vicksburg having made many enemies through his tendency to scorn superiors and play favorites among his inferiors. Nevertheless, the close working relationship that developed between Porter, Grant, and Sherman during the Vicksburg Campaign set the standard for joint operations in the West.

Porter’s conduct of his fleet during the Vicksburg campaign was unimpeachable. After months of failure trying to move infantry on the Memphis-Vicksburg overland line, it was Porter’s daring runs past the Vicksburg batteries on April 16 and 22, 1863 that moved enough river transports below the city for Grant to launch the decisive operation from the south. Porter's sailors were the first to occupy the abandoned Confederate base at Grand Gulf and, as Grant's army neared Vicksburg in mid-May, Porter set up a forward supply depot that allowed Grant to keep his troops supplied as they settled into final phases of the Vicksburg campaign. After the infantry invested the city in May, Porter's gunboats provided additional firepower to the Federal forces, lobbing roughly 22,000 shells into the Confederate fortifications over the course of the 39-day siege—an average of 564 per day. After the Confederate surrender, Porter, Grant, and Sherman shared a bottle of wine on the U.S.S. Blackhawk.

Fact #7: Vicksburg had its own Crater more than a year before Petersburg.

On June 23, Grant’s engineers completed a bold project. After weeks of tunneling, they had arrived at a spot directly underneath the 3rd Louisiana Redan, a stronghold on the Confederate fortification line. They spent the next day moving 2,200 pounds of gunpowder into position under the redan.

At 3 P.M. on June 25, they lit the fuse. After a few tense moments the redan blew sky-high and Gen. John A. Logan's infantry went into the resultant crater with a shout, supported by cannon and musketry from all along the Union line. However, the tumbling debris happened to form a new parapet that commanded the crater. Confederates swiftly occupied the parapet and began to roll artillery shells with lit fuses into the struggling mass of blue soldiers. The attack was cut up and stalled. Union engineers eventually moved into the crater and erected a shielding casemate of earth and wood debris, allowing the infantry to withdraw without further loss.

On July 1, Grant’s engineers informed him that they were days away from completing a network that would set off thirteen more explosions simultaneously. Such an assault would have had a good chance of seizing the entire city, but the events of July 3 rendered the network unnecessary.

Despite middling success of this explosive attempt to break the siege, Grant nevertheless assented to a similar plan thirteen months later when his forces were stalled outside Petersburg, Virginia.

Fact #8: Grant demanded an unconditional surrender at Vicksburg—and was rebuffed.

On July 3, 1863, white flags began to appear above the Confederate fortifications. Then John Pemberton rode out into no-man’s land—Grant went to meet him. Pemberton wanted to open negotiation for the surrender of the city and his army.

Early in the war, Grant earned the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” for the terms he bluntly offered to the Confederate garrison at Fort Donelson, Tennessee. He made the same offer at Vicksburg, but Pemberton refused. The two men parted with only an agreement to a brief cease-fire. Later that night, Grant relented. He offered parole to Pemberton and his army, which the Confederate general accepted. The surrender was finalized the next day, July 4, 1863, and the Union army took control of the city. In recognition of that day, the townsfolk of Vicksburg did not celebrate Independence Day for 81 years following the siege.

Fact #9: The capture of Vicksburg split the Confederacy in half and was a major turning point of the Civil War.

In the few days it took for Grant’s message announcing the capture of Vicksburg to reach Abraham Lincoln, the President had also received word that Port Hudson, the only other Confederate stronghold left on the Mississippi, had also fallen. “The Father of Waters once again goes unvexed to the sea,” he proclaimed.

With no length of the Mississippi River now safe from Union power, the Confederacy was unable to send supplies or communications across its breadth. Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas were cut off from the rest of the rebellious nation. This was doubly damaging, as the Texas-Mexico border was a favorite route of secessionist suppliers and the possibility of French intervention across the border was precluded by the nigh-impassable boundary of a Union-held Mississippi River. The fall of Vicksburg came just one day after the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg, prompting many to point to early July, 1863 as the turning point of the Civil War.

Fact #10: The American Battlefield Trust Trust is engaged in an ongoing effort to preserve battlefield land around Vicksburg.

In 1899, Confederate veteran Stephen Dill Lee supervised the establishment of the 1,800 acre Vicksburg National Military Park, which was then transferred to the National Park Service in 1933. The park was the site of the raising of the ironclad USS Cairo in the 1960s, one of the landmark achievements of American Civil War preservation. Despite its significance, the other battlefields of the Vicksburg campaign, were largely unpreserved until recent years. The American Battlefield Trust has saved hundreds of acres on the battlefields of Raymond, Champion Hill, Big Black River Bridge, and Port Gibson.

Bonus Facts:

- Grant removed his senior corps commander, John McClernand, during the siege after McClernand released a self-congratulatory order extolling the virtues of his troops and maligning the efforts of Sherman and McPherson during the May 22 attacks.

- Col. Benjamin H. Grierson led 1,700 Federal horsemen through Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana, created confusion in the Confederate heartland, and diverted Pemberton's attention from Grant's massing forces in Louisiana.

- Inaccurate artillery fire frequently struck buildings in the City of Vicksburg, prompting civilians to live in a series of subterranean caves for protection.

- During the Vicksburg Campaign, the U.S.S. Cincinnati, which had been sunk on May 10, 1862 and subsequently raised, earned the dubious distinction of being one of the few naval vessels ever to be sunk twice.

- The S.S. Sultana, which exploded on April 27, 1865, made a stop in Vicksburg to take on more passengers before continuing its ill-fated journey.

- The Vicksburg National Cemetery is the final resting place for over 17,000 Union and Confederate soldiers who died during the Vicksburg Campaign.

- 31 states have memorials or monuments commemorating the contribution of their citizens during the Vicksburg Campaign.

Learn More: Vicksburg Animated Map

Related Battles

861

767

446

515

2,457

3,840

4,910

32,363