Port Gibson

Claiborne County, MS | May 1, 1863

Obtaining the full control of the Mississippi River was an early and vital war aim for the Federals. The Mississippi served as a highway to move men and materials from places as far a ways as Pittsburgh to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico, and in early 1863, only two Confederate strong points stood between the Federals and dominance of the mighty river.

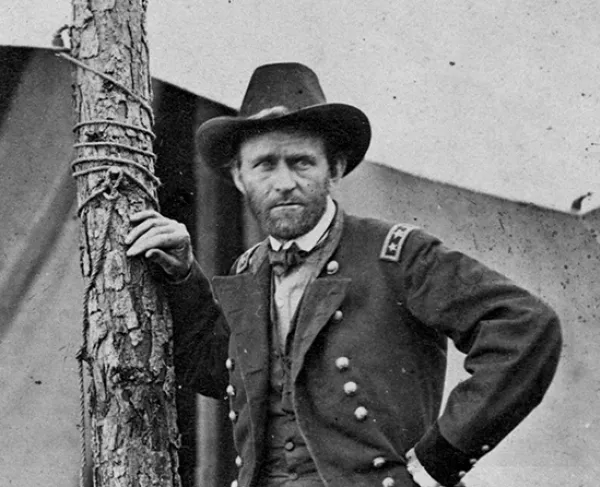

The first strong point on the Mississippi was the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy,” Vicksburg. Situated atop dominate bluffs overlooking a sweeping bend of the river, Vicksburg was a tough nut to crack. Time and again Ulysses S. Grant tried and failed to approach the bastion city. A late 1862 advance south from Tennessee ended with Confederates severing Grant’s supply lines. William T. Sherman attempted to storm the city but came up short at Chickasaw Bayou. Canals were dug and abandoned. Levees were blown up to create flood plains only to carry the boats too high in the water, literally among the branches of the trees. Nothing seemed to work. In late April, Grant finally struck gold. Utilizing some diversions, he marched his army down the western side of the river while Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter ran his flotilla of gunboats and transports past the Confederate guns of Vicksburg. The two forces reunited some 30 miles south of the city, and on April 29-30, Porter’s sailors were transporting Grant’s army across the river into Bruinsburg, Mississippi—unopposed.

Now on the Vicksburg side of the river, Grant’s men marched toward their first objective, Port Gibson, situated roughly ten miles east of Bruinsburg, which commanded the local road network. The road over which the blue soldiers now marched led to the Shaifer House, roughly 1.5 miles from Port Gibson.

Confederate Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green was inspecting his picket line at the Shaifer House shortly after midnight when he was amused to see Mrs. Shaifer and the women of the house frantically loading a wagon with all their household items. The general tried to calm their fears by telling them that the enemy could not possibly arrive before daylight. Just then, a single shot rang out as the Confederate pickets spotted movement in the distance. The stillness of the night was shattered as a volley of musketry came in reply. Many of the bullets buried themselves in the wagon-load of furniture. The women were terrified and, screaming with fright, leaped into the wagon and whipped the animals toward Port Gibson.

Green quickly mounted and raced back to Magnolia Church to alert his brigade. Fighting in the scattered fields and forest around the Shaifer House intensified as more Union regiments and batteries came into action. Night fighting such as this was rare during the Civil War because it was difficult to maintain command and control of the troops. Almost by mutual consent, the fighting ebbed by 3:00 a.m., and the weary soldiers in blue and gray rested on their arms.

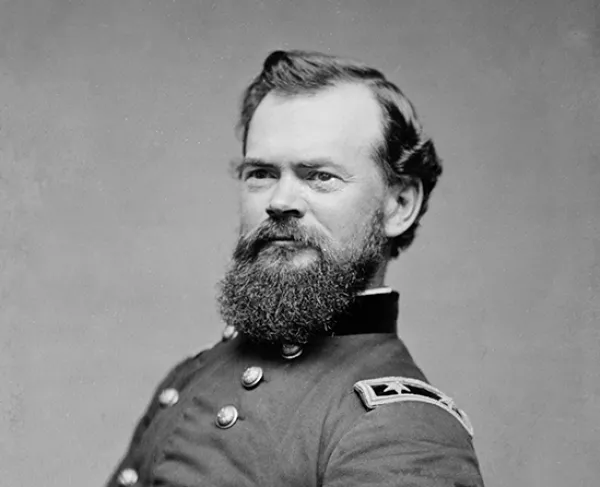

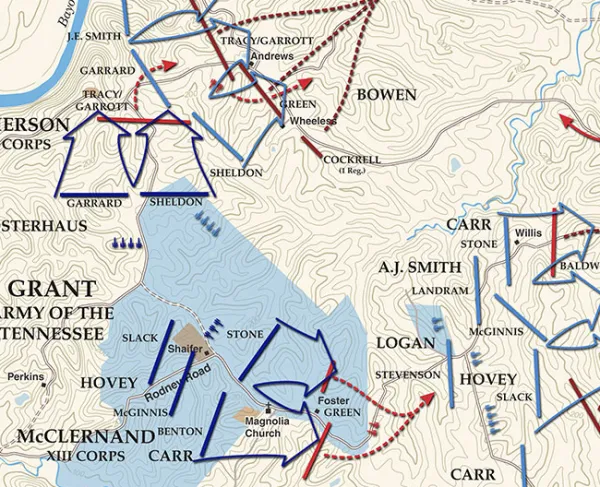

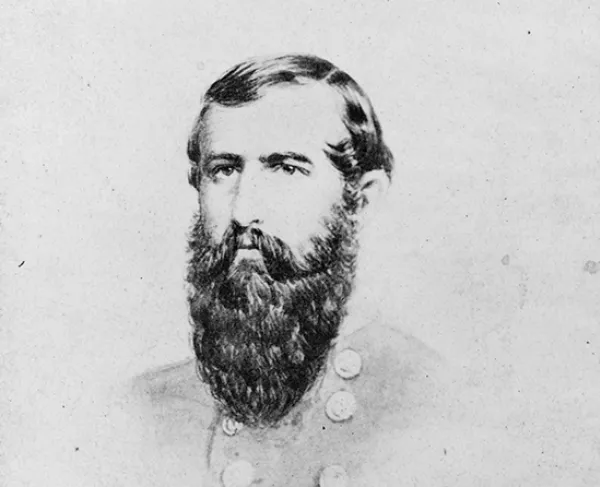

At dawn the battle was renewed in fury as Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand threw most of his XIII Corps toward Green’s thin gray line. Green called for reinforcements from Brig. Gen. Edward Tracy, who anchored the Confederate right flank roughly a mile and half to the northwest. Tracy dispatched infantry and artillery to Green’s assistance minutes before cannons began to pound his own line, signaling the advance of a new Union column under Brig. Gen. Peter Osterhaus. Soon after, Tracy was killed by a sniper’s bullet.

Despite the reinforcements, Green was still heavily outnumbered, and at around 10:00 a.m., his line collapsed. As Green’s men scrambled to the rear, Brig. Gen. John Bowen, in overall Confederate command on the field, worked feverishly to restore his line. The brigades of Brig. Gen. William Baldwin, just arriving from Vicksburg, and Col. Francis Cockrell’s from Grand Gulf, were placed into position astride the road at White and Irwin’s Branches of Willow Creek, a mile and a half east of Magnolia Church.

The Confederate right did not last long. The Union troops pushed forward all along the line, and fierce fighting continued throughout the afternoon. A desperate Confederate counterattack by Cockrell’s Missourians was repulsed, and Bowen ordered a retreat. The remaining garrison at Grand Gulf was evacuated the next day. The Battle of Port Gibson was a resounding Union victory that secured Grant’s beachhead east of the Mississippi River and cleared the way to the Southern Railroad supplying Vicksburg.

Port Gibson: Featured Resources

All battles of the Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg Campaign

Related Battles

23,000

8,000

861

767