September 13, 1862. In a field flanking the east side of the Washington Pike just outside of Frederick, Maryland, two Union soldiers—Corporal Barton W. Mitchell and First Sergeant John M. Bloss—settled for a rest. Just feet away, tall grass concealed an envelope and three cigars. When a private found and called their attention to the envelope a few minutes later, these soldiers of the 27th Indiana Infantry quickly surmised its importance. It became one of the greatest intelligence discoveries of the American Civil War.

Four days earlier, on September 9, 1862, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee and his staff met in his headquarters tent on the Best Farm, on what is now the Monocacy Battlefield. They faced a stubborn problem. When Lee invaded Maryland, he expected the Federal garrisons at Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), to evacuate northward. They did not. These two garrisons, totaling about 13,000 men, sat across the entrance to the Shenandoah Valley, where Lee hoped to draw his supplies from as he moved north toward Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. As long as they remained in place, Lee could not continue his advance. Further complicating matters, General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac was advancing toward Lee from Washington, putting a timer on how long his army could safely remain in Frederick.

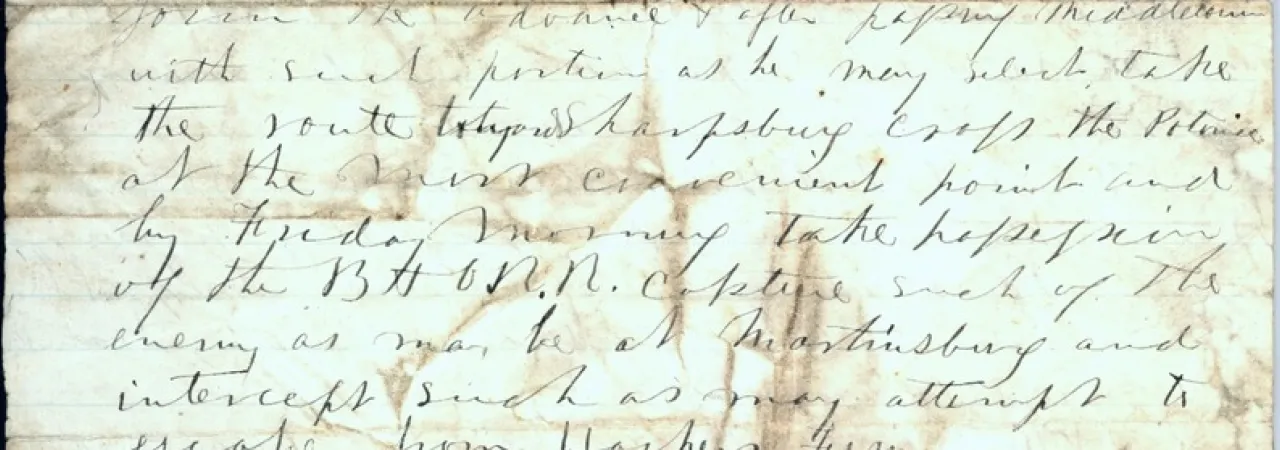

Lee and his staff crafted a new set of orders for the army to both stymie McClellan’s advance and open up the Shenandoah Valley for supply. Titled Special Orders No. 191, they stipulated that the army divide itself into four parts: three sections, under Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, to encircle and besiege Harpers Ferry, and one, under Longstreet, to defend the mountain passes between Frederick and the Cumberland Valley. The plan violated the military principle that one should not divide his force in the face of a superior enemy. Lee, however, was confident he could destroy the garrison at Harpers Ferry before McClellan could force a major battle. Lee gave Jackson just three days to accomplish his objectives and reunite the army.

Lee's chief of staff, Robert H. Chilton, drafted the orders. Seven copies were made, each addressed to the senior officer of the four groups or members of Lee's staff. It soon emerged that General Daniel Harvey Hill, one of Jackson’s division commanders, would be operating independently of the four groups outlined in the orders. Chilton prepared another copy to be given directly to Hill. However, through normal command procedure, Hill had already received a copy of the orders from Jackson directly, making Chilton’s copy redundant. Chilton did not know this and sent his copy to D. H. Hill anyway. This copy became the “Lost Order.”

Hill claimed he never received it. In an 1888 letter to the editors of Battles and Leaders, a clearly frustrated Hill stated:

My adjutant-general made [an] affidavit, twenty years ago, that no order was received at our office from General Lee. But an order from Lee’s office, directed to me, was lost and fell into McClellan’s hands. Did the courier lose it? Did Lee’s own staff lose it? I do not know.

Chilton, on the other hand, adamantly believed that the orders had been received at D.H. Hill’s headquarters. Postwar, the matter of who had lost the orders and how became a heated debate; many argued in defense of Lee’s character or attacking Hill’s character, rather than examining the facts. The postwar accounts are thus both conflicting and misleading. Many witnesses to the 1862 Maryland Campaign wrote accounts about these lost orders, all are shadowed by personal loyalties to either man, and there is no definitive proof to indicate which is the "true" story.

Exactly who lost the orders and when is thus lost to history. It could be that the dispatch was lost en-route to Hill’s headquarters, but it was found in the same field where his division was bivouacked. Unless it unknowingly fell out of the courier’s pocket, that seems unlikely. It could be that an officer at D. H. Hill’s headquarters refused to take possession or otherwise disposed of the redundant copy without signing for it, but that would also be a grave violation of military procedure. Considering it was found wrapped around three cigars, a considerable prize, this also seems unlikely. Without any authoritative source one can only speculate. Whatever the case, the orders were lost, with major consequences for Lee’s campaign.

Four days later, on the morning of September 13, Lee’s army was behind schedule. Far from being concluded, the Siege of Harpers Ferry had yet to begin. General Lafayette McLaws’ division captured the Maryland Heights early in the morning, and General John G. Walker’s division reached the Loudoun Heights later in the day. Jackson’s troops did not arrive until the afternoon. D. H. Hill’s Division alone, supported by General J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry, guarded the Catoctin and South Mountain passes. The balance of General James Longstreet’s corps, meanwhile, was with Lee in Hagerstown. The army was dangerously scattered.

Around midmorning Alpheus Williams’ First Division of the Union Twelfth Corps arrived near Monocacy Junction, southeast of Frederick. They crossed the Monocacy River at Crum’s Ford and scattered off the road for some much-needed rest. Colonel Silas Colgrove, commanding the 27th Indiana, had just settled in to rest when two men reported to him with an envelope wrapped around three cigars. “Within a very few minutes after halting,” Colgrove recalled, “the order was brought to me by First Sergeant John M. Bloss and Private B. W. Mitchell, of Company F, 27th Indiana Volunteers, who stated that it was found by Private Mitchell near where they had stacked arms. When I received the order it was wrapped around three cigars, and Private Mitchell stated that it was in that condition when found by him." Colgrove, recognizing its importance, took the document to division headquarters. Alpheus Williams, commanding the division and acting commander of Twelfth Corps, examined it. The letter could very easily be a forgery, or, even if genuine, a trick. Could it be trusted?

The division’s adjutant-general, Samuel Pittman, immediately recognized the handwriting. Before the war, he had worked in the Michigan State Bank’s Detroit branch as a teller and as part of his duties processed checks from Robert Chilton, who kept an account there while serving as a paymaster in the Regular Army nearby. Chilton, now Lee’s chief of staff, had penned the orders! Thus authenticated, Pittman carried the orders to army headquarters. Affixed to the orders was Williams’ endorsement, in which he wrote “it is a document of interest & is also thought genuine."

General George B. McClellan’s headquarters already buzzed with rumors and reports of dubious quality that were, in most cases, impossible to authenticate. Lee’s army was somewhere close in front of him. He knew that much from his cavalry. But exactly where Lee’s army was and in what strength: those details had eluded him. Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry screen across Catoctin Mountain blinded McClellan to what lay beyond. McClellan could lunge forward, but without precise knowledge of Lee’s whereabouts McClellan didn’t want to stab out into the unknown. When Pittman arrived at McClellan’s headquarters in Frederick shortly before noon, the general was meeting with a group of local citizens. Handed the orders mid-meeting, historian Stephen Sears described McClellan's reaction: “he threw up his hands and exclaimed (according to one of his visitors), ‘now I know what to do!’”

McClellan, after analyzing the orders with his staff, passed them on at 3pm to General Alfred Pleasonton, commanding the army’s cavalry, and ordered him to confirm whether the Confederates had acted on the orders. By nightfall, McClellan believed he possessed the current operating orders of Lee’s army. He quickly wrote and disseminated orders for the whole army to begin moving west at dawn, over Catoctin Mountain, and attack the Confederates guarding the passes over South Mountain.

That evening a southern sympathizer who had been at McClellan's meeting informed J.E.B. Stuart of the disastrous news: McClellan had a copy of Lee’s orders and was rapidly moving west. Stuart passed this report to Lee in Hagerstown. When Stuart’s dispatch reached Lee around 10pm, he discussed the news with Longstreet. Lee insisted that Jackson should continue the siege of Harpers Ferry. To give Jackson time to complete the capture, Lee ordered Longstreet to march to Boonsboro and reinforce Hill. The combined force would attempt a delaying action, buying time for Jackson to capture Harpers Ferry and then reunite with Lee. Hours later, shots rang out near Fox’s Gap on South Mountain, the opening salvo of the decisive phase of Lee’s ill-fated expedition into Maryland.

Further Reading:

An Invitation to Battle: Special Orders 191, Monocacy National Battlefield,

- Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command Volume II by Douglas Southall Freeman (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1971).

- Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam by Stephen Sears (New York: Essential Classics of the Civil War Book of the Month Club, 1994).

Related Battles

12,401

10,316

2,325

2,685

12,636

286