John David Hoptak, for Hallowed Ground

In our Fall 2012 issue of Hallowed Ground, four historians made a case for why their respective battle was the pivotal moment of the 1862 Maryland Campaign. Historian John Hoptak made the case for the Battle of South Mountain.

Though far too often overlooked and relegated to the footnotes of history, the September 14, 1862, Battle of South Mountain must rank as the pivotal moment of the Maryland Campaign. Long languishing in the shadows cast by Antietam, the Battle of South Mountain, fought three days earlier and several miles east of that meandering-but-swift creek, marked the first major battle fought north of the Potomac River.

It was here — not Antietam — where Lee’s first invasion of Union soil was initially met and turned back. Casualties sustained on South Mountain exceeded 5,000 men killed, wounded, captured or missing. When the smoke cleared, Gen. Robert E. Lee had experienced a major tactical defeat as an army commander and ordered a retreat, prepared to end to his bold gamble north of the Potomac. Conversely, Maj. Gen. George Brinton McClellan and his Army of the Potomac had achieved victory over Lee’s vaunted Army of Northern Virginia which, only two weeks earlier, had thoroughly crushed Maj. Gen. John Pope’s army at Second Manassas. Morale in the Union army soared, which paid high dividends when the armies again came to blows three days later in the otherwise peaceful farming fields surrounding Sharpsburg, Md.

For Lee, the campaign had begun with high hopes. When his army began crossing the Potomac on September 4, it became the only eastern Confederate army to operate in Union territory since the commencement of hostilities 17 months earlier. He hoped to achieve yet another decisive battlefield victory, but things quickly went wrong and the campaign produced nothing but headaches for Lee. His army, while confident, was exhausted; straggling was so prevalent that Lee later claimed to have lost one-third of his force before the first shot was fired at Antietam. The Union garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry did not immediately evacuate their posts, forcing Lee to divide his army to clear his intended lines of supply and communication down the Shenandoah Valley. He wished to remove this proverbial thorn in his side within just three days, but the timetable quickly slipped.

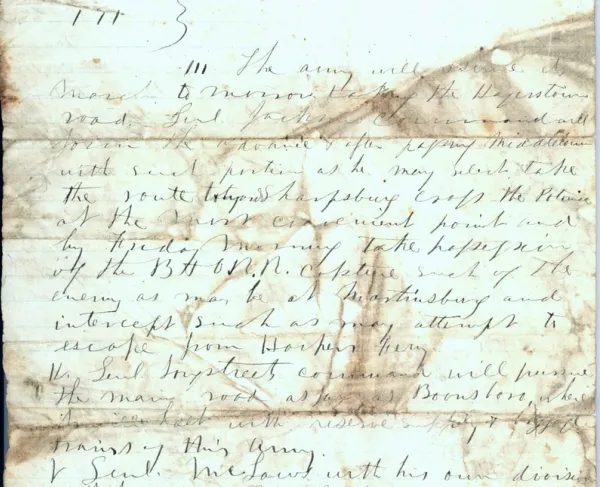

Even worse, Lee operated without knowing the precise whereabouts of the fast-moving Army of the Potomac, leaving him vulnerable. The final elements of Lee’s army did not evacuate Frederick until noontime on September 12; four and half hours later, the van of McClellan’s force — Maj. Gen. Jesse Reno’s IX Corps —reached the city. The following morning, as the Union army continued to gather at Frederick, Cpl. Barton Mitchell of the 27th Indiana happened upon a copy of Lee’s Special Orders No. 191, the infamous “Lost Orders” that detailed the full Southern strategy. Hoping to catch Lee “in a trap of his own making,” McClellan sought to push west from Frederick the following day, cross South Mountain and “divide the enemy in two and beat him in detail,” while simultaneously relieving the beleaguered Union force trapped at Harpers Ferry.

It was not until late on the night of September 13 that Lee discovered just how precarious his situation was; his own army was still widely divided, and the Army of the Potomac lurked just east of South Mountain. For the first nine days of this campaign, Lee had called the shots, but now he was on the defensive. He ordered one of his divisions, under Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill, to hold the three South Mountain passes “at all hazards,” urged his subordinates at Harpers Ferry to hurry things along and, on the morning of September 14, raced Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s command back from Hagerstown to aid Hill.

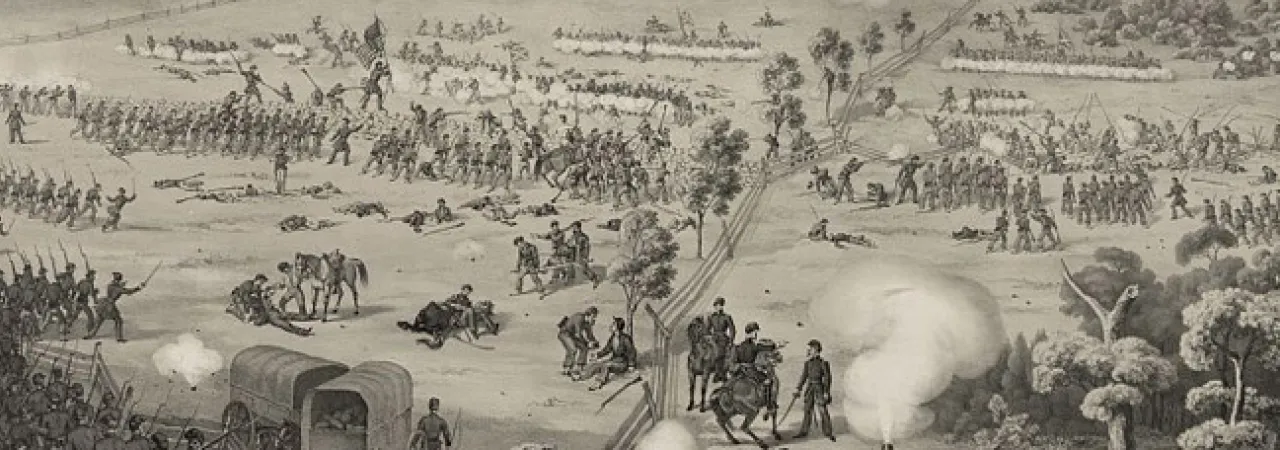

Lee’s men fought valiantly to stave off the seemingly relentless tide of blue sweeping up the slopes. Though outnumbered, they did enjoy the defensive advantage, atop the heights. But Union troops under Reno, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker and Maj. Gen. William Franklin fought and clawed their way up a hillside that Hooker deemed steep enough it would be difficult enough to ascend “even in the absence of a foe in front.” After a day-long struggle in which more than 5,000 men became casualties, McClellan’s forces had secured Crampton’s and Fox’s Gaps, as well as the roadway leading to the lesser-used Frosttown Gap. A Confederate brigade under Col. Alfred Colquitt clung to Turner’s Gap, where the National Pike crossed South Mountain, but with Federal troops on either flank — and approaching in even greater numbers — Lee came to the painful realization that the game was up.

Reluctantly, Lee ordered a retreat—and an abandonment of the campaign. The following morning, however, fearing that he would be forsaking Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, with no less than 20 percent of his army, Lee halted. Several hours later, learning from Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson that the surrender of Harpers Ferry was imminent, Lee determined “to make a stand upon those hills” west of Antietam Creek, hoping to salvage this campaign and gain that victory for which he had come north. But he and his army were already pressed up against the ropes by an aggressive McClellan and his rejuvenated Army of the Potomac. After the 13-hour slugfest at Antietam, with his army severely weakened, Lee realized there was no more to be gained in Maryland and ordered his battered force back into Virginia.

Antietam was the culmination of Lee’s first invasion of Union soil, but it was at South Mountain where the tide turned in favor of the Union, making it the pivotal moment of the tremendously consequential Maryland Campaign.

Learn More About the Pivotal Moments of the Maryland Campaign: The Case for Antietam | The Case for Harpers Ferry | The Case for Shepherdstown

John David Hoptak works as an interpretative park ranger at Antietam National Battlefield and is an adjunct instructor at American Military University. He is the author of several books, including The Battle of South Mountain, part of The History Press’s Sesquicentennial Series, and blogs on Civil War topics at www.48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com.

Related Battles

2,325

2,685