Faneuil Hall

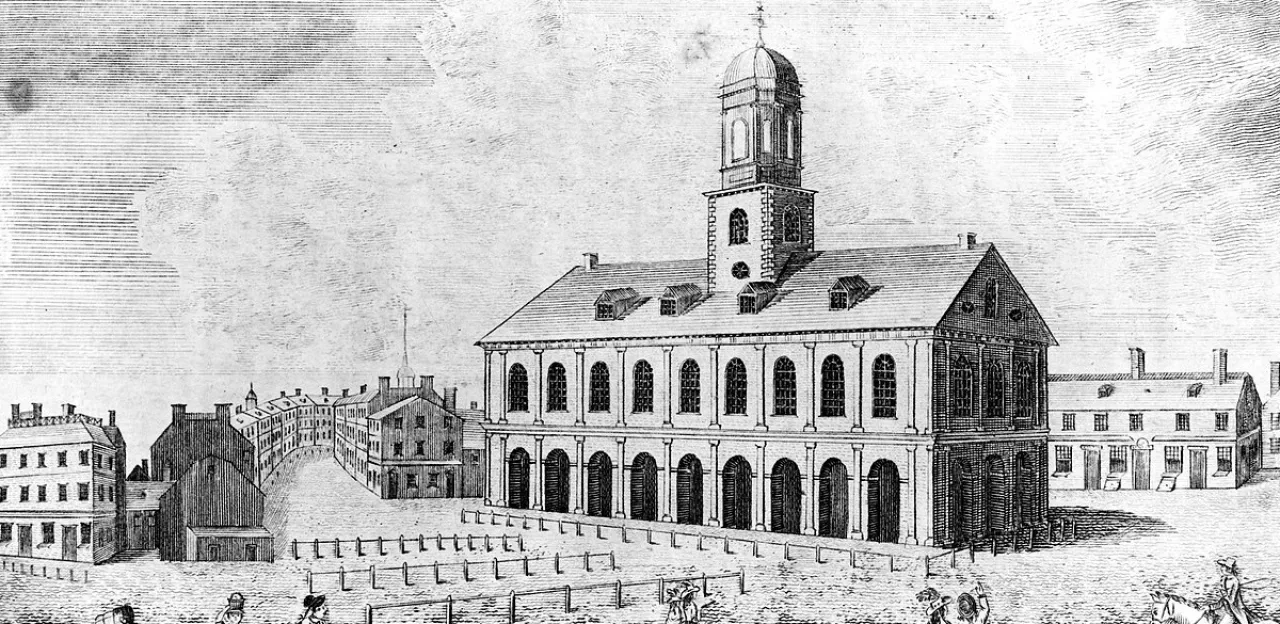

Often referred to as “The Cradle of Liberty,” Faneuil Hall is a marketplace and meeting hall where many of the debates and discussions about American liberty occurred throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Faneuil Hall was a gift to the city of Boston from the wealthy merchant Peter Faneuil, who it was named after. The massive hall was completed in 1742 in Dock Square in downtown Boston. The first floor of the building was a marketplace and above it was placed a meeting hall. Some of Boston’s townspeople were suspicious of centralizing the town’s market, but the ultimately accepted it by a slim margin of seven votes and Boston’s town meeting hall was moved into Faneuil Hall. The hall was gutted by a fire in 1761 but reopened in 1763.

As the center of Boston’s town meetings, Faneuil Hall was witness to many of the debates leading up to the American Revolution. Patriots James Otis and Samuel Adams gave stirring speeches in defense of American liberty in the meeting hall and Bostonians discussed the burdens of British taxation and control. Patriots arrived at the “no taxation without representation” argument from Faneuil Hall. Bostonians protested the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts, and the arrival of British soldiers in 1768. The bodies of some of the victims of the Boston Massacre laid in state at the hall in 1770 before their funeral and burial. In 1772, the Boston Committee of Correspondence was created at Faneuil Hall to help connect Boston with the other American colonies. Meetings were also held here in the lead up to the Boston Tea Party in 1773, one becoming so large that it was moved to the Old South Meeting House.

After the Boston Tea Party, the British passed the Coercive Acts (or known by the Bostonians as the Intolerable Acts) and abolished the town meetings and British soldiers were quartered in the hall. Additionally, the British used the meeting space as a theatre for officers in the army. Following the bloodshed at Lexington and Concord and the beginning of the Revolutionary War, British General Thomas Gage disarmed the citizens of Boston and stored the weapons in Faneuil Hall.

Following the Revolution, the hall continued to be a central place in Boston society and local government. In 1789, George Washington was entertained here during his New England tour as president.

In 1806, the hall was expanded and enlarged to its current dimensions and in 1826 the Quincy Market, North Market and South Market were added onto the first floor marketplace to greatly expand the space for commerce on the site. The Hall continued to be the site of the Boston town meeting up until 1822 when the town of Boston became the city of Boston and moved out of Faneuil Hall. However, the hall continued to be the center of intense meetings, speeches and debates up through the 20th century.

In the mid 19th century, the meeting hall was witness to heated debates about the future of slavery in the lead up to the American Civil War. Among the speakers in the hall were John Quincy Adams, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and even future President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis. In the words of abolitionist Wendell Phillips: “Those who cannot hear free speech had better go home. Faneuil Hall is no place for slavish hearts.” Later in the 19th century and early in the 20th century, women suffragists and labor activists argued for women’s rights and better working conditions at Faneuil Hall.

Today, the site is part of the city’s Freedom Trail and millions of visitors see the hall and the marketplace every year. On the top floor of the building today is a military museum and armory of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts, which has been its headquarters since 1746. High above the marketplace, a weathervane in the shape of a grasshopper has graced the cupola of the hall since 1742 and has become a famous symbol of the city of Boston. Faneuil Hall continues to stand as a beacon for self-government and free speech. As was described during the centennial of American independence in 1876, it was Faneuil Hall that “kindled that divine spark of liberty, which, like an unconquerable flame, has pervaded the continent.”