When George Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States of America, the parameters and power of the president were to be determined. As president, like when he was general-in-chief of the Continental Army, Washington had to set the standard for all who followed him into the office. The list below represents some of the major things Washington did first as president that established a precedent for future leaders of the position.

Appointing Judges

One of the first challenges that President Washington faced was filling the vacancies in the newly created Judicial Branch of the federal government. It would fall on Washington to nominate qualified candidates to appointment to fill these seats. Some judges only served a handful of years before moving onto other ventures or retirement. In all, Washington appointed 38 judges to the federal court system.

Ceremonial Purposes

The presidency was supposed to be subservient to the Legislative Branch upon creation, but having George Washington serve as the nation’s first president instantly created a cult of personality around the position. He was the face and main attraction of the entire government. Because of this, Washington was invited to attend just about every local ceremony that honored a new building or ship being constructed. He laid the cornerstone for the future Capital Building in the city that would carry his name in 1793. He officially recognized Thanksgiving with a declaration that Thursday, November 26, 1789 was to be a federal holiday, a first.

Chief Foreign Diplomat

The Executive Branch serviced foreign policy relations, and the president would serve as the primary diplomat to all nations. Washington welcomed envoys from Spain, France, and Great Britain during his presidency, as well as dozens of members from various Native American tribes. Though he believed the position to be one of importance and needed to be shown respect, Washington did not believe the president was above seeing and speaking with envoys. The American presidency was not a European monarchy and Washington wanted that to be known whenever possible. Welcoming delegates and foreign ambassadors on an equal footing with him showed the difference.

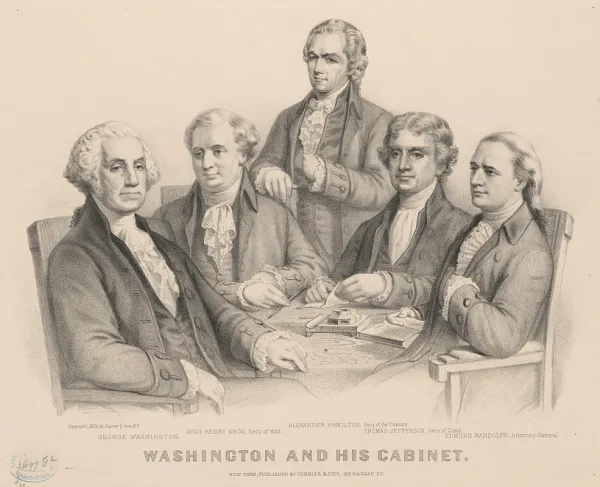

Establishment of a Cabinet

One of the uncertainties at the start of the new federal government would be how the various tasks of implementing the government’s policies were to be handled. The government had to function, and experienced individuals needed that could be trusted with performing these responsibilities. Washington took it upon himself to nominate people who would serve in his inner circle of personal secretaries. The decision was his alone to make. Harkening back to his military family of aides and secretaries during the American Revolution, the president sought to emulate this with his cabinet selections. He chose two former military colleagues, Alexander Hamilton as Treasury Secretary and Henry Knox as Secretary of War. For Secretary of State he chose Thomas Jefferson. Washington’s cabinet combined some of the greatest minds of the early republic.

Commander in Chief of the Military

The United States did not have a standing army at the time of Washington becoming president. The country only had a reserve force of about one thousand soldiers. Standing armies were highly suspicious to most Americans; militias that could be raised quickly still commanded the proper response to any threat. The role of the president was always shaped to command the military, if necessary. Despite reservations of one person holding too much power, it was generally accepted that a military would need a singular leader. Washington being Washington settled any worries over who would command an army, if needed. He would briefly lead the assembled army in 1794 during the Whiskey Rebellion, being the first of only two American presidents who commanded US soldiers on American soil. The other was President James Madison outside the capital during the War of 1812.

Mr. President, and Nothing More

A famous squabble broke out early on in Washington’s presidency over the proper title to address him by. Vice President John Adams, seemingly bored or investing far too much into the matter, took it upon himself to come up with several official titles to address the president by. All sounded long, European, and ridiculous to the members of Congress who listened. Eventually, Washington himself decided the matter by declaring the title as, “Mr. President,” to reflect the non-monarchial stature of the position.

No Lifetime Appointment

Among all the things Washington continued to exemplify during his career in public service was his reluctance to accept power, and his insistence on relinquishing it when he could. At each critical phase in his life, he stepped away when absolute power was his to wield. First in 1783, he resigned as commander in chief of the Continental Army. In 1789, he was persuaded yet again to serve his country as the first president. Washington hoped the appointment to president would be temporary, but it was not to be so. The partisanship of the 1790s consumed his administration and he was forced to remain in office for eight years or two presidential terms. By 1796, he was exhausted and decided to retire, permanently. The precedent of carrying out a maximum of two consecutive terms was established by his retiring in 1797. This precedent went unchallenged until President Franklin Delano Roosevelt won a third term in the 1940 election. Roosevelt secured a fourth term in 1944 but died a few months later in April 1945. The Twenty-Second Amendment of the Constitution places term limits on an individual who is president, converting Washington’s precedent of two terms into law as the maximum a person can serve.

Further Reading

- His Excellency: George Washington: By Joseph J. Ellis

- The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon: By John Ferling

- Washington: The Indispensable Man: By James Thomas Flexner