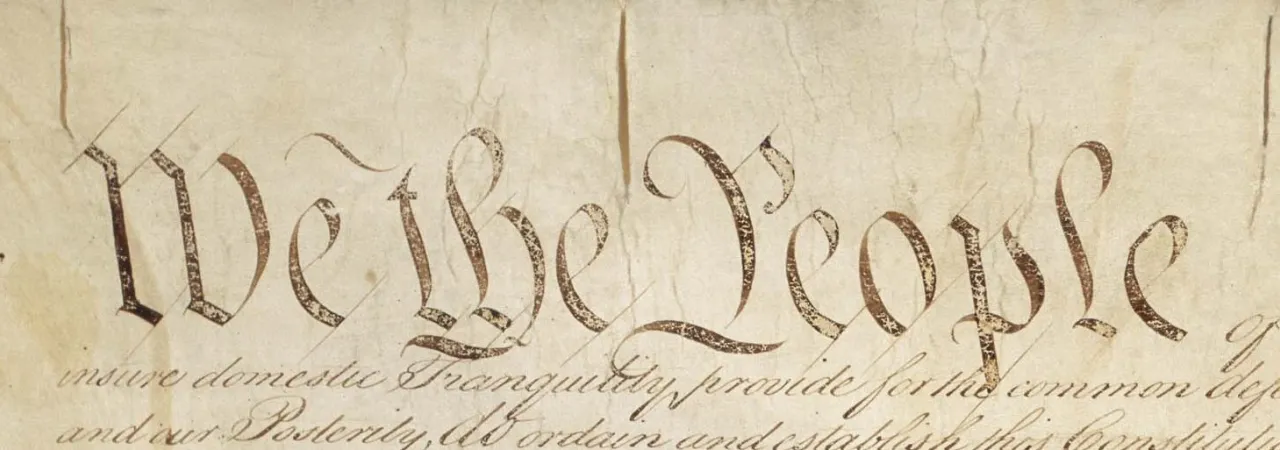

The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America form the bedrock of the American Charters of Freedom, a group of documents which also includes the Bill of Rights. All three are enshrined in the Rotunda of the National Archives in an altar-like setting. Abraham Lincoln referred to these documents, particularly the Declaration of Independence, as American scripture, even using the phrase "American civil religion" when he invoked the Declaration’s place in American memory.

We tend to take the Charters of Freedom for granted and hardly recognize that the Constitution was deliberately written in the present tense to make it a “living document.” While these documents are all related, they each have a unique history which helps us to understand their importance and meaning. Together they establish the United States' guiding principles on which people are not bound by tribe, race, religion, or language.

Declaring Independence

Americans celebrate the 4th of July as the day of Independence, but John Adams, one of the drafters of the Declaration of Independence, thought otherwise. Adams believed that “the day of deliverance” was July 2nd, 1776, the day Congress actually voted to declare independence from Great Britain. On July 4th Congress refined some of the language in the document.

Unlike John Trumbull’s painting of the event that hangs in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, in which all fifty-five signers appear gathered together, the document was actually signed over a long period of time. Jefferson’s sublime anthem that “all men are created free and equal” from the Declaration's Preamble was roundly cheered at the time, but continues to be defined by each generation of Americans.

Thomas Paine’s pamphlet, Common Sense, published in 1776, influenced the drafters of the Declaration of Independence. Paine argued in succinct terms that ordinary people had the capacity to govern themselves and did not need to be led by a crowned official. This argument alone made the American Revolution a turning point in history. Common Sense inspired many Members of Congress and American colonists alike. the pamphlet became a sensation and bestseller throughout the thirteen colonies. The Declaration articulated Paine’s ideas in a more formal manner, declaring separation between England and her American colonies.

The timing of the Declaration’s release is interesting to note. Armed conflict with British forces broke out in Massachusetts in April 1775. By July 1776 George Washington’s rag-tag Continental Army was preparing a defense of New York, anticipating a large British attack. The President of the 2nd Continental Congress, John Hancock, sent a copy of the Declaration to Washington on July 6. On July 9 Washington had the document read to his assembled troops. In the eyes of the British, all of the signers of the document and those now fighting to defend it were engaged in treason. Within six weeks, Washington’s army would be routed in New York and by the following December the Continental Army was on the verge of disintegration.

In many respects, the American Revolution and subsequent War for Independence were a product of the Enlightenment, the 17th-century intellectual movement in Europe that sparked new ideas about humanity, science, government, human rights and reason combined with a sense of liberal nationalism. The most influential European philosopher on the American Revolution was Englishman John Locke, who at the end of the 17th century expanded the notion of the social contract between those governed and those governing. Locke’s philosophy of the “social contract” greatly influenced Thomas Jefferson and its influence runs throughout the Declaration of Independence.

Beyond the colonies, Locke’s philosophy and the works of other Enlightenment thinkers influenced many men of privilege living in Europe in 1776. These individuals, some with a military pedigree, like the Marquis de Lafayette (France), Casmir Pulaski (Poland), Thaddeus Kosciusko (Poland), Johan DeKalb (Bavaria), and Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben (Prussia) were excited by the possibilities that the new United States offered the world. Many of them wanted to be part of the historical moment. It helped that Benjamin Franklin represented the United States abroad in foreign governments, mostly operating out of Paris. Franklin was the portal through which many of these foreign fighters found their way to the new United States. The prospect of securing a high rank in the nascent American Continental Army played a role as well. Most importantly, the zeal of freedom was firmly entrenched in their hearts and minds. When news of the Declaration of Independence reached Europe, it was electrifying!

Crafting the Constitution

While the Revolutionary War continued, the 2nd Continental Congress had essentially become by default a quasi-government. One of their first orders of business was to provide a framework of government for the fledgling nation-colonies. With expediency in mind, Congress adopted the Articles of Confederation, which created a loose confederation between the new “states.” The Articles created a weak central government with limited authority. By the time the war ended in 1783, no one was certain if the thirteen states were a collective that made one sovereign nation or thirteen independent nations. Problems and disagreements soon erupted between the new states so that by 1787 it was apparent that the government needed to clarify what the "United States" meant.

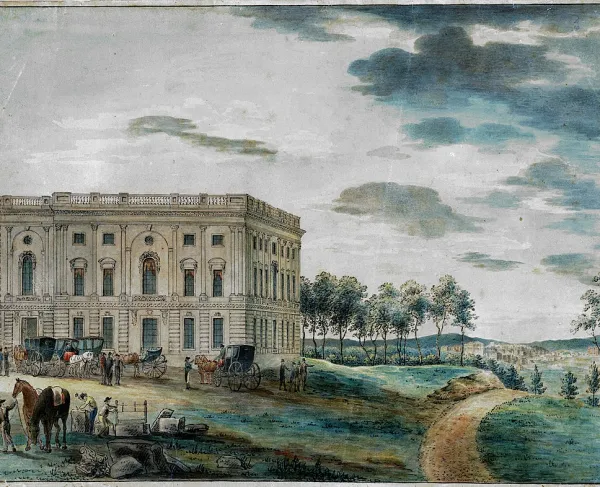

On May 25, 1787, delegates from twelve states (Rhode Island refused to send a representative) assembled once more in Philadelphia to revise the ineffective Articles of Confederation. Their first order of business was to appoint someone to preside over the meetings. Once more, George Washington was tapped for his leadership skills. For four months delegates debated, argued, and compromised in secrecy. The Constitutional Convention ended on September 17, 1787 with an entirely new system of government envisioned for the American people.

A federal republic had been created with three separate branches of government: an executive, legislative, and judiciary. The Constitution divided power between the state and the federal governments. James Madison, called "Father of the Constitution" as he laid out most of the language, skillfully argued for the document before the Congress. Of the fifty-five men assembled for the Convention, only thirty-nine put their names on the document. Everyone knew it was an imperfect document. Benjamin Franklin said afterwards, "I confess that there are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them... I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution... It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies…”

With the Convention concluded, the delegates returned to their respective states with the document in hand and each state would hold its own separate Ratification Convention. Once three-quarters of the states ratified the Constitution, it would become the law of the land. Four of the states that ratification depended on were the wealthiest and most populous: Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. The Federalist Papers, published under the pseudonym of Publius, but written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, played a crucial role in securing the Constitution’s ratification in these lynchpin states.

It is said that as the Convention ended in September 1787, the aged Benjamin Franklin, the oldest member of the assembly and one of only a few Americans to sign both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, left the Pennsylvania State House and was approached by a woman who allegedly inquired, “So Dr. Franklin, what do we have?” “A Republic, if you can keep it” he is supposed to have replied. Now it is up to us.