One of the most remarkable things about the Declaration of Independence in 1776 is that only a year previously most Americans were not thinking about independence. American colonists, by and large, hoped that the conflict with Great Britain could be resolved with their rights as Englishmen preserved within the British empire.

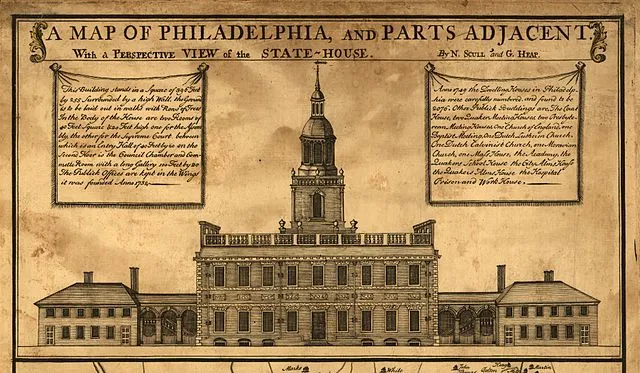

The path to independence really began when delegates from twelve colonies gathered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the fall of 1774. This was the First Continental Congress and an important milestone as the united colonies looked to repair their relationship with Great Britain. The gathering came as a response to the very harsh Coercive Acts that were passed earlier that year and was the first major inter colonial meeting since the Stamp Act Congress of 1765. Many of the delegates were not supportive of independence (and did not have the authority to act on this) and instead they petitioned that the King repeal the Coercive Acts (also known as the Intolerable Acts). They also formed the Continental Association to boycott British goods. When these measures were ignored by Great Britain, the delegates agreed to reconvene in May of 1775 for a Second Continental Congress.

By the time the Second Continental Congress convened, the first shots of the Revolutionary War had already been fired at Lexington and Concord. On April 19, 1775, hundreds of British and American troops were killed and wounded in the bloody battle. The debates over authority and rights had finally broken out into armed combat. On hearing the news, George Washington wrote, “Unhappy it is though to reflect, that a Brother’s Sword has been sheathed in a Brother’s breast, and that, the once happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched with Blood, or Inhabited by Slaves.”

With war under way, and no official central government, the Second Continental Congress served as the de facto American government. On June 14, 1775, the Congress created the Continental Army and named George Washington as its commander in chief. Washington took command of the army which was then besieging the British garrison in Boston. Before he arrived in Massachusetts, another major battle occurred at Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. In this battle, British regulars charged numerous times against an American fortified position on Bunker (or Breed’s) Hill. The British lost over a thousand men killed and wounded but were ultimately successful in driving the Americans from their position. Among the slain was the prominent Massachusetts patriot, Joseph Warren.

In Philadelphia, the Congress passed a Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, outlining the need for the army to defend themselves from the British Army. They made clear in this document that “We have not raised armies with ambitious designs of separating from Great Britain, and establishing independent states.” They argued that the British government had forced them into this last resort. On July 8, 1775, the delegates approved an Olive Branch petition to King George III, seeking his intervention in stopping the bloodshed and restoring their rights as Englishmen. However, the King refused to accept the petition, since he had already issued his Proclamation of Rebellion in response to the Battle of Bunker Hill. The King declared the American colonists to be in “open and avowed rebellion.”

Now declared to be in rebellion and with the war raging, delegates began to think independence was inevitable. In March of 1776, General George Washington successfully in fortified Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston and forced the British Army to withdraw from Boston. This impressive victory by the Continental Army over the British was a big morale boost and emboldened more leaders to speak of independence from Great Britain. However, the Continental Congress did not have the authority to declare independence without the permission of the individual colonial governments.

The Continental Congress then began to look to individual colonial governments to give permission to their delegates to vote for independence. North Carolina was the first state to give their delegates permission to declare independence when they passed the Halifax Resolves on April 12, 1776. On May 15, 1776, Virginia’s legislature declared their own independence and instructed their delegates to vote for independence.

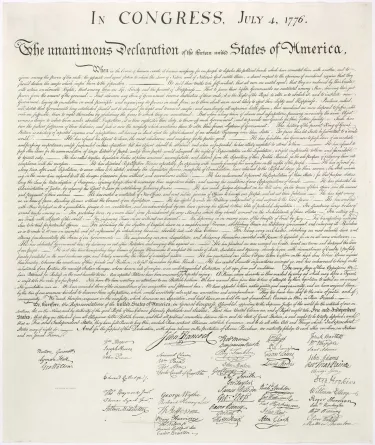

On June 7, 1776, Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee put forward the motion to the Second Continental Congress “that these united colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” While the Congress debated this motion over the next few weeks, a Committee of Five was established to write a Declaration of Independence in the event the motion passed. That committee was made up of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert R. Livingston.

By July 1, the delegates from New York, South Carolina, Pennsylvania and Delaware were still not on board with independence. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina believed that a declaration of independence would come later, but seeing that the measure would still pass, agreed convince the South Carolina delegation to vote in favor to make the resolution unanimous. On July 2, two members of the Pennsylvania delegation that opposed independence were convinced to be absent. Caesar Rodney of Delaware rode throughout the night to arrive in time and swing Delaware’s vote in favor of independence. The New York delegation, still with no direction from the colonial government, agreed to abstain from the vote. The vote on the Lee resolution was held on July 2, and it passed unanimously with 12 yes votes and 1 abstention. The colonies had now voted for independence.

John Adams jubilantly wrote to his wife Abigail that “The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

Those celebrations did and still do occur, but on July 4 instead of July 2. On July 4, the Committee of Five presented the Congress with the finalized Declaration of Independence, and Congress approved it. The path to this moment was long and arduous, but the thirteen British colonies were now declared free and independent states. In order for the new United States to take their place among the nations of the world, they needed foreign recognition and to defeat the British military that was at that moment gathering in New York harbor. Much of the future hung in doubt, but the men of the Second Continental Congress were willing to sacrifice their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to secure America’s independence.