“Summer soldiers and Sunshine patriots” - The American Crisis

The fall and early winter of 1776 was the low point of the war for the American cause. Beginning that summer, the British had struck with a vengeance in an attempt to end the American rebellion in one knock-out blow. In July, over 20,000 British and German soldiers landed on Staten Island in preparation to capture the vital port of New York. When the attacks finally began the following month, Washington and the Continental Army were nearly powerless to stop them. Washington was pushed off Long Island on August 27th, and his whole army only avoided capture through a miraculous night evacuation to Manhattan. The British did not relent, however, and on September 15th they landed nearly unopposed on Manhattan and secured New York City. The city would remain in British possession until the end of the war.

In the weeks and months that followed, Washington’s army suffered defeat after defeat at the hands of General Howe’s British and German forces. American defenses were outflanked by British landings in what is now the Bronx (October 18, 1776), forcing Washington to pull northward to avoid encirclement. Howe caught up with Washington ten days later at the Battle of White Plains (October 28, 1776), driving Washington further from New York and the remaining Continental troops there. Howe turned back to deal with these cut off garrisons, decisively defeating the Americans at Fort Washington (November 16, 1776) and capturing nearly 3,000 men. Washington’s army, which had numbered nearly 20,000 Continentals and militia in the late summer, was reduced to less than 5,000 effective soldiers as casualties and desertions began to mount. To make matters worse, many of those remaining had limited enlistments that were set to expire in the winter.

Recognizing that Washington’s situation was dire, General Howe continued to push onward into New Jersey. The Continental Army remained elusive, as Washington pushed his exhausted and demoralized men across New Jersey to deny Howe the opportunity for one final decisive battle. The American commander’s goal was to cross the Delaware River to the relative safety of Pennsylvania, and from there try to rekindle the American cause. Among the steadily waning column of soldiers following him was the 39-year-old English immigrant, Thomas Paine.

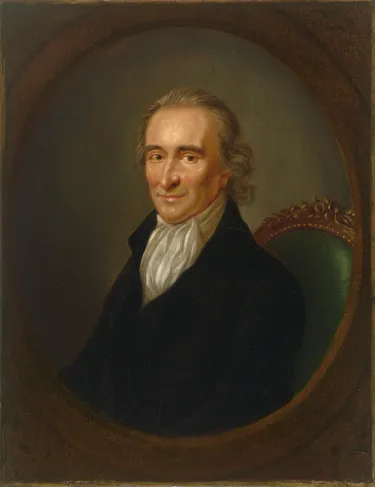

Born in Thetford, Paine initially followed in his father’s footsteps as a maker of lady’s stays (a corset-like undergarment). He was never successful in business, however, and by 1774 he had separated from his wife and prepared to move to the colonies to avoid debtor’s prison. Arriving in Pennsylvania with the help of Benjamin Franklin, Paine found work as the editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine. The magazine gave Paine a forum for his increasingly radical liberal politics, and he would advocate for the abolition of slavery, worker’s rights, and American independence. Although he personally abhorred war, Paine gradually began to see tyranny as a worse evil.

Thomas Paine became a household name in both the colonies and in Great Britain in January 1776 with the publication of Common Sense. Within a few months over 100,000 copies of the pamphlet had been printed and distributed. Its strength lay in Paine’s ability to discuss complex and important events in terms that the average person could readily understand. Today, Common Sense is recognized as an important catalyst for the rise in popular support for the revolution. He saw the American Revolution as just the beginning of a worldwide struggle against oppression and for the rights of the average man. Later that year, Paine joined the army as a staff officer for General Nathanael Greene. As he moved through the army camps, soldiers referred to him by the nickname “Common Sense” and adored him for the complimentary dispatches he wrote for the Pennsylvania Magazine.

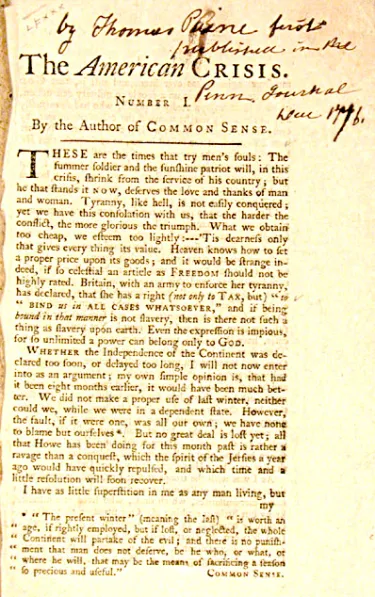

In late November 1776, during the Continental Army’s darkest hour, Paine again picked up the pen with the hope of recreating the enormous success of Common Sense. “It was necessary” he later wrote, that “the country should be strongly animated.” As the wrecked army crawled across New Jersey, Paine took advantage of every stop to put words to paper. He often wrote late into the evenings by the flickering light of a campfire, as exhausted soldiers slept huddled nearby. As Washington’s army crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania, he put the finishing touches on his latest pamphlet – The American Crisis No. 1.

First published in Philadelphia on December 19th, The American Crisis No. 1 was an appeal to the patriotism and resolution of the American people. It’s opening lines are some of the most well-remembered and oft-quoted in American history.

“THESE are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.”

The words electrified the demoralized army and became the rallying cry that Paine had hoped for. Within a day, copies were printed and distributed throughout the Continental Army, and officers read it to their assembled men. Militiamen who had returned home in disgust just a month before took up arms once again. Civilians up and down the Delaware River Valley reaffirmed their commitment to the cause of independence. Desertions among the Continentals slowed, and soldiers quoted The Crisis in their watchwords while on picket duty. On the night of December 25th, as Washington prepared to make a strike on Trenton, he ordered that Paine’s words be read to the entire army as a reminder of the importance of their task.

“I call not upon a few, but upon all: not on this state or that state, but on every state: up and help us; lay your shoulders to the wheel; better have too much force than too little, when so great an object is at stake. Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it.”

Their resolve renewed, the battered but not broken Continental Army went back on the offensive. The “Ten Crucial Days” that followed saw Washington and his men victorious at Trenton and Princeton, forcing the Howe to abandon much of New Jersey. Loyalists, emboldened by Howe’s earlier success, now found themselves abandoned to the wrath of their patriot neighbors. As winter gave way to spring, new enlistments from throughout the colonies poured into Washington’s army. The military victories at Trenton and Princeton changed the course of the war in a strategic sense, but The American Crisis No. 1 provided the ideological motivation that made them possible.

The American Crisis No. 1 was first of thirteen pamphlets published in the series, which would continue until the end of the war in 1783. Many of the future pamphlets reinforced the sentiments of the first, in their appeal to the patriotism of the American people to see the war through to its end. Others were ostensibly to “Lord Howe” or the “People of England” and highlighted what Paine saw as the injustice of the British government and the futility of trying to conquer America. These future volumes of The American Crisis continued to sell well and were distributed across the nation, but none would share the widespread recognition of the first. From the darkest days of the revolution came a piece of legendary American writing that continues to provide inspiration nearly two and a half centuries later.

Further Readings

- Washington’s Crossing By: David Hackett Fischer

- The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine By: Phillip S. Forner

- Common Sense By: Thomas Paine

-

Common Sense, Rights of Man, and Other Essential Writings of Thomas Paine By: Thomas Paine

-

American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804 By: Alan Taylor