The Federalist Party: Creating a New Government

Of all the things the Federalist Party can be labeled among its enemies of the era, no one could undermine the very nature of its inception. The concept of American republicanism was at the forefront of its creation in 1787; what its members fought for tooth and nail would largely be enshrined in the Constitution a year later. However, the debates that followed ratification continued to question whether the party was solely about applying the Constitution and the new federal government in ways that upheld the principles of the American Revolution, or whether they deliberately tried to undermine them.

By design, the Federalists are the very first official American political party. Birthed during the summer of 1787 during the arguments for creating the Constitution, its principle membership counted among its advocates no less than George Washington, Gouverneur Morris, Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay. But how these men of influence came together in the spring of 1787 rests on understanding the circumstances that were crippling the young nation.

Following the end of the American Revolution, the United States was under several grave situations that were combining to undermine the ability of the government to function. At the time, the Articles of Confederation were the adoptive national government. Proposed in 1777 during the war, and finally ratified in 1781, the Articles created a collection of thirteen sovereign governments in the thirteen states. Each state essentially held one vote in the Confederation Congress over national matters. A drawback to the Articles was how it placed all financial authority with the states. This proved to be disastrous in pulling funds together for national emergencies, best showcased during the war by the inability of Congress to fund supplies and pay the Continental Army. With the American economy struggling in the mid-1780s, there was confusion and disagreement on how to properly manage the country’s economic interests. In addition, the country owed tremendous amounts of debt to foreign entities. Both states and individual

American citizens had borrowed on credit to pay for the war. The instability this caused, along with the depreciated value of American currency, threatened a financial ruining of American credit. No one understood this better than George Washington.

At the height of the war, among his many talents as commander in chief, Washington had to straddle commanding the American army while also dealing with the realities of American politics. He saw firsthand the ineffectiveness of the Confederation Congress to meet the needs of the war. By 1780, in private letters, he was calling for a complete overhaul of the country’s government. By war’s end, with several attempted mutinies behind him, Washington grew skeptical of the Articles. But he was committed to retirement and chose to conduct business from Mount Vernon. For the next three years, he wrote an impressive correspondence with others who worried the government was not working. Washington, the hero of the Revolution, was in favor of a stronger central government that could further the national agenda. A committed nationalist in the eighteenth century-republican sense, he concluded the Articles could not meet the demand set forth by winning independence. Something had to be done, but it was not exactly clear what.

In 1786, veterans of the war in western Pennsylvania rebelled against local tax collectors. Shays’ Rebellion, as it became known, splashed over the continental newspapers and seemed to amplify worries that the Confederation government could not effectively govern. Other proponents of making changes used the situation to alarmist momentum, and soon a convention was called for in Annapolis to discuss revisions to the government. But the convention failed to produce any enthusiasm for amending the Articles. The few that remained committed sought a second convention in Philadelphia in the spring of 1787 to make recommendations. Many of the eventual attendees in Philadelphia had already decided revising the Articles was not enough. Something far more radical had to be proposed.

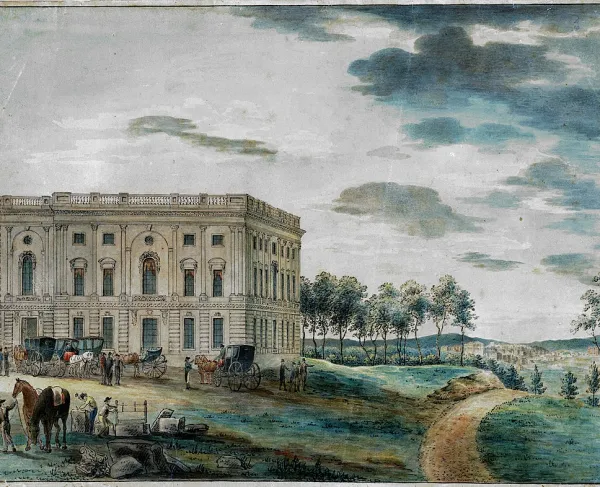

The body of delegates at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787 who called for a brand new plan of government, one that would scrap the Articles completely and start anew, would be labeled the Federalists. Among the many new proposals championed by its membership, the concept of a separation of powers delegated over three separate branches of government: one legislative, one judicial and one executive, became the nucleus of their deliberations. From there, they pivoted with proposals seeking a strong chief executive, a national bank insured by the central government, and a legislature that would be bicameral. Unfortunately, this also opened them up for ridicule. When Hamilton addressed the Convention, he praised the British monarchial system and advised the future American president should emulate a king in many ways. Gouverneur Morris, a Federalist and critic of democracy, spoke candidly for abolition and that slavery threatened to undermine the forces of liberty throughout the country. Antifederalists quickly seized on the comments, staunchly digging in for a fight to upend the Confederation, thinking the real intentions behind the Convention was to usurp the self government principles won in the American Revolution. Washington’s position as president of the Convention and his backdoor diplomacy likely saved the following months of arguments and compromises from folding.

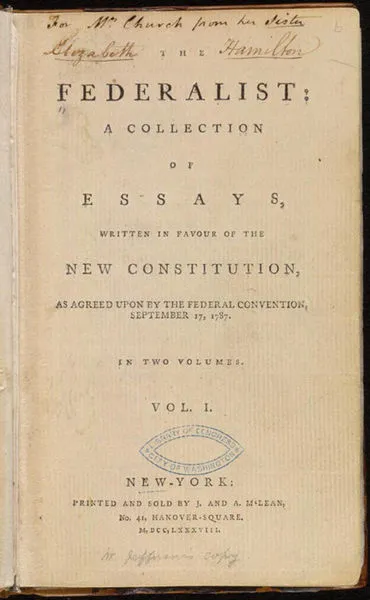

With the Convention wrapping up in September 1787, the Constitution was officially completed in text, with Morris writing the Preamble, but now it needed to be debated and ratified among the several states. Because of certain compromises over-representation and the separation of powers between the federal and state governments, many leading Federalists assumed smaller states would vote to ratify on the grounds that they would be receiving the same equal status as larger states. The states with the most power: Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia proved to be where the fiercest debates occurred for ratification. Antifederalist opposition was strongest in rural New York and Virginia whereas New York City, a merchant-based economy, saw benefits in ratification. A majority of newspapers throughout the many states supported the federal Constitution. Hamilton, Madison, and John Jay would pen eight-five essays under the pseudonym Publius between October 1787 and April 1788, later printed as The Federalist Papers, to argue for ratification. The essays by the three men justified why the Articles of Confederation had failed, and why they needed to be replaced with the current proposal. Ultimately, the Federalists won the ratifying conventions by a narrow margin.

The new federal Constitution forever changed the United States. The many problems brought on by the Articles of Confederation had now been eliminated, in theory. But new problems soon emerged that would divide the young nation’s political apparatus into factions. Federalists like James Madison would soon rapidly change sides as new debates on the powers and functions of the federal government came under scrutiny. Madison would become one of the leading Antifederalists within two years of George Washington becoming the first president. Alexander Hamilton’s monetary schemes established the United States financial sector, but also led to deep opposition that set up the partisanship of the 1790s. The Federalists had won the argument and ratification. But tensions within the government and the United States drastically undercut their ability to govern in the years to come.

Further Readings

- Gouverneur Morris: An Independent Life By: William Howard Adams

- Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution By: Richard Beeman

- Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention, May to September 1787 By: Catherine Drinker Bowen

- Triumvirate: The Story of the Unlikely Alliance That Saved the Constitution and United the Nation By: Bruce Chadwick

- The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789 By: Joseph Ellis

- The Federalist Papers By: Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison

- The Return of George Washington, 1783-1789 By: Edward Larson

- Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788: By Pauline Mainer