Early Capitals of the United States

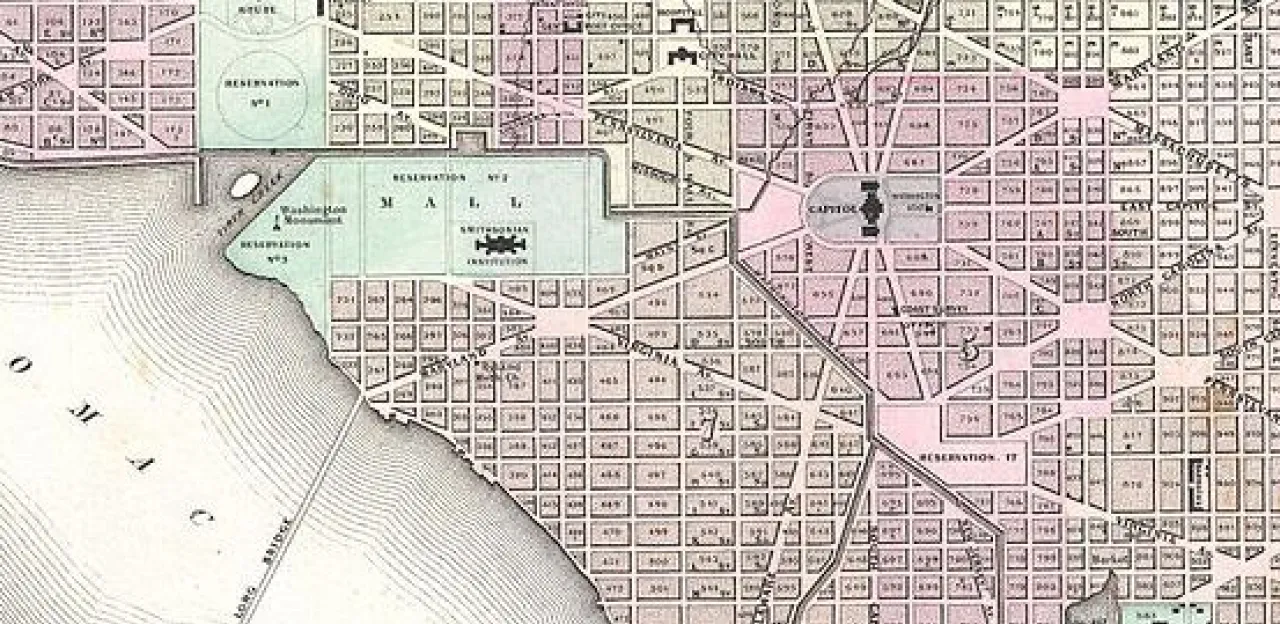

On July 16, 1790, George Washington signed the Residence Act of 1790. This Act decreed that the National Capital, and permanent seat of government, would be established along the Potomac River on land gifted by Maryland and Virginia. In addition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, would become the temporary capital until 1800, the deadline for the permanent capital to be completed, which would be named Washington, D.C.

Before this Act, and before the United States formed the government we know today, North American autonomy was discussed in New York. On June 18, 1754, twenty representatives of Northern Atlantic Colonies met in Stadt Huys, the Dutch phrase for “city hall,” in Albany, New York. Delegates amongst varying North American British colonies discussed defense tactics during the French and Indian War; however, the conference veered away from purely military strategy to the “Albany Plan of Union.” This plan combined the colonies “under one government as far as might be necessary for defense and other general important purposes.” Spearheaded by Benjamin Franklin, this plan asked the British Crown to elect a President General and Grand Council for the colonies to dictate treaty making, military ventures, and taxes for the Colonies. The Plan was sent to the British Board of Trade in London for approval and was rejected. North American autonomy was not discussed again until the Stamp Act Congress met from October 7 – 25, 1765, in New York, New York. This Congress was established in response to the Stamp Act that taxed all paper goods. In this Congress, delegates announced that Great Britain had no right to tax the American colonies without American representation. The monarchy repealed the Stamp Act, but immediately passed the Declaratory Act that stated that Parliament could create any law and bind the colonies to it without American representation.

With these Acts, the revolutionary fervor of the Colonies ignited. The next time the delegates met, they had formed the First Continental Congress in 1774. The Congress convened in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In Carpenters’ Hall, the Congress discussed how the colonies could collectively respond to the continual taxation from the British Crown and the enforcement of the Intolerable Acts, which punished Boston after the Boston Tea Party. From this meeting, the Colonies decided to collectively boycott British Goods and to write a petition to the King to stop the enforcement of these taxes and restrictive measures. The King rejected this petition. After that rejection, the Second Continental Congress was established and convened in Independence Hall in Philadelphia. From 1775-1781, the Congress met and worked toward unifying the colonies in their fight against the British in the Revolutionary War.

Because of British hostilities during the Revolutionary War, the Second Continental Congress migrated between numerous cities. When the British threatened to overtake Philadelphia, the Congress moved from Pennsylvania to Baltimore, Maryland from December 20, 1776, to February 27, 1777. Their meeting spot was the Henry Fite House, which burnt down in 1904. After returning to Philadelphia, the British once again threatened the city. In September of that same year, the delegates raced across Pennsylvania, passing through Lancaster for a day and then settling into York, Pennsylvania to reconvene. Once the British left Philadelphia, the delegates were able to return to the city in June 1778.

While they roamed through the American Colonies, the Congress decided they needed guiding documents to instruct how the Provisional Government should operate. The Congress drafted and then ratified the Articles of Confederation on March 1, 1781. This document named the new country “The United States of America” and the Second Continental Congress was renamed into the Congress of the Confederation. This Congress did not have a set capital. From 1781-1783, they remained in Philadelphia. However, in 1783 there was a soldier riot of Revolutionary War comprised of veterans demanding compensation for their military service. With little funds to pay them back, the Congress moved to Nassau Hall (which at one time was the largest building in the colonies) on the College of New Jersey’s campus to distance themselves from the riots. Nassau Hall still stands, and the College of New Jersey has been renamed to Princeton University. The Congress’s inability to pay veterans revealed fundamentally problems in the current government under the Articles of Confederation. Since the states were worried about a tyrannical central government, the Articles severely limited the Congress’s power especially in their ability to impose taxes. With no ability to raise funds, they could not pay veterans or promise money to the soldiers currently fighting in the Revolutionary War. Money was raised through state initiatives and a variety of other schemes.

Nevertheless, the Congress continued to work under the current Articles. While in New Jersey, the Congress received their first foreign minister, which were diplomats from the Netherlands, and received word that Great Britain had signed the Treaty of Paris. In November of 1783, the Congress continued onto Annapolis, Maryland to meet in the unfinished Maryland State House. In Maryland, George Washington resigned as the Commander-and-Chief of the Continental Army. Meanwhile, Congress ratified the Treaty of Paris. With that ratification, the Revolutionary War ended, and the United States had its full autonomy. By August 1784, the Congress had moved once again to Trenton, New Jersey. In New Jersey, the Congress accepted the resignation and farewell of Marquis de Lafayette. Throughout these moves, the Congress continued to struggle to operate under the current administration. Legislation could only pass if there was a majority decision among the states, nine states among thirteen must consent to the measure. If only one delegate was in attendance from that state or if the delegates did not agree, then that state could not cast a vote on a measure. With these limitations, measures were routinely voted down and little progress was made in the new nation. A new plan of government began to be discussed.

In the summer of 1787, the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to discuss a new system of government. While there, delegates from each state met to discuss how to consolidate power while ensuring that checks and balances were in place to limit tyrannical control of a centralized government. By the New Year, the delegates sent their Constitution to the Congress of the Confederation, who were meeting in New York, New York, for consideration. While there, the Constitution was heavily debated. The first two political parties emerged from these debates: Anti-Federalists were against while the Federalists were for the new Constitutional measures. Even with this intense debate and disagreement, the Constitution was sent to each state to ratify the new legislative document. On June 21, 1788, nine out of thirteen states, had ratified the Constitution. The new government began operating under the new Constitution on March 4, 1789 in New York, New York.

On April 30, 1789, George Washington took oath of Office as the First President of the United States at Federal Hall in New York City. Federal Hall was demolished in 1812, but the Nation that George Washington preceded over still lives on. Since 1800, Washington, D.C. is the permanent seat of the United States Government.