“These are the times that try men’s souls...” is one of the most recognizable lines of literature from the American Revolutionary War era. Penned by Thomas Paine during the dark days of the retreat of the Continental Army, in his treatise The American Crisis, after the devastating defeats around New York in 1776. The cause of American independence was truly hanging in the balance.

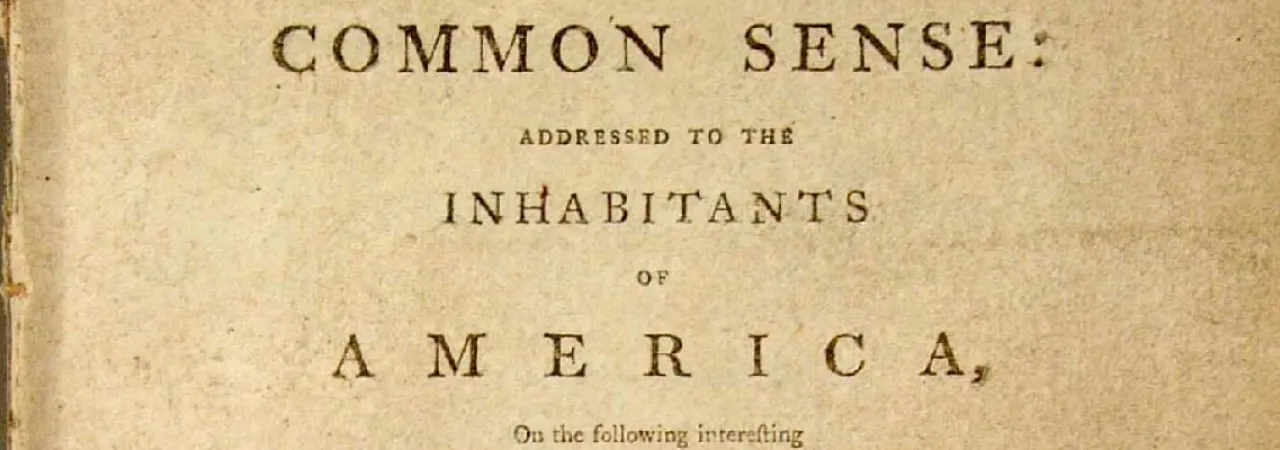

Before the cause of American independence could be rallied by the powerful and persuasive message that emanated from the pen of Paine in late 1776, the cause had to be ignited. One of the tracts that coalesced and gave voice to the prospect of a rupture with Great Britain was due in part to the same Thomas Paine.

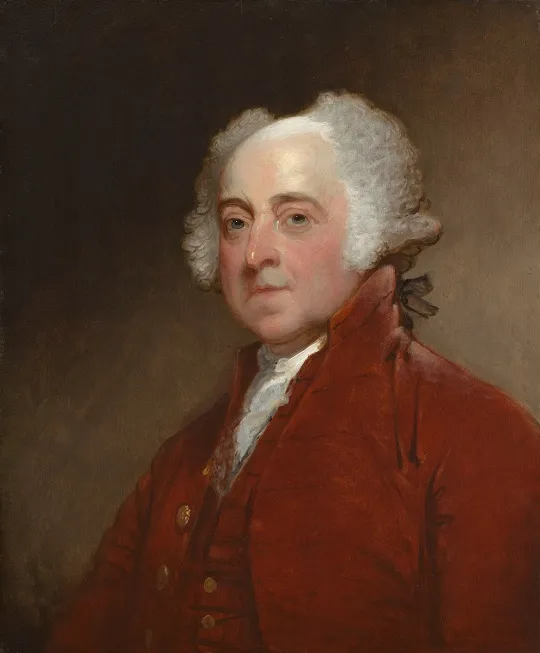

In fact, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, John Adams described the impact of Paine’s first and most wildly successful pamphlet Common Sense; “Without the pen of the author of Common Sense, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain.” Lofty praise for Paine and his literary contribution to the American Revolutionary War-era history.

First, who was the author? Born Thomas Pain in on January 29, 1736, in the old-style calendar (February 9, 1737, in the calendar used today) in Thetford, England, to a tenant farmer and stay-maker Joseph Pain and his wife Frances. By 1769, Pain added the vowel (e) at the end of his name. After numerous occupations in England, including a brief sojourn on the high seas as a privateer, and the death of one wife and separation from another, Paine took up residence in London. Through the connection with mathematician George Lewis Scott, he was introduced to Benjamin Franklin. A mention in conversation with Franklin led to Paine immigrating to Colonial America in October 1774.

Only two brief instances in Paine’s life prior to America gives one insight into any potential impact on what would transpire once his boots landed in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774. First, he had become active in civic engagements while living in the town of Lewes, which had a long tradition of pro-republican sentiments. Secondly, in the summer of 1772, he was the author of an article entitled, The Case of the Officers of Excise and had taken an active hand in helping distribute over 4,000 copies throughout London. Yet, even these brief windows into Paine’s past does not hint at what his pen would do in the colonies.

By the following March, Paine was the editor for the Pennsylvania Magazine and contributed two articles to the January 1775 to the inaugural magazine. As the publication was self-styled an “American magazine” the hope was that it would combine sentiment and gain readership throughout the 13-colonies. Paine became the editor and brought a political presence to the publication. Crafting a series of letters that would be farmed out to various papers in the city, once the quill touched parchment, Paine’s genius with words flowed forth under the title of Plain Truth. Dr. Benjamin Rush, a luminary in Philadelphia and soon to affix his signature on the Declaration of Independence, suggested the title Common Sense. The latter title, discarded for the pamphlet, did speak to the genesis behind the publication, as Paine’s motive was to spread the idea of independence from Great Britain, republican ideology, and recruitment for the military. Rush though also made the connection to the Philadelphia printer and publisher Robert Bell who quickly saw the potential and published the entire pamphlet.

Although demand ran high for and a second edition was advertised, Paine still could not remove himself from confrontation. When Paine requested people investigate what the profit was from Bell’s printing of the pamphlet in his publication, the startling sum of zero was what they found. Paine, who had begun writing a few appendices to the initial Common Sense, contacted the publishers of the Pennsylvania Evening-Post, the Bradford Brothers. This printer would go on and publish the new addition and follow-up appendices that Paine created. Bell remained obstinate and had advertised that another edition would be forthcoming from the anonymous author of the first pamphlet, which was a direct contradiction of Paine’s response to him. Both sides traded barbs, took to print to publish variations, and new additions as 1777 wore on.

The result of these initial publishing, according to estimates, exceeded 100,000 copies by the end of 1776 and from Paine himself, the estimate that over 120,000 in the first ninety-days from the original publication. Some estimates range as high as half-million copies within the first twelve months whereas other later historians put the number in the 75,000 range.

No matter the number, the reach was astronomical and was not confined to just one side of the Atlantic, as the pamphlet made its way into print in Great Britain and was widely read in France as well. The latter country’s publishers did omit the overt references to the evils of monarchy that Paine elaborated on in the pamphlet.

Paine, who forsook his copyright on the work, allowing the pamphlet to be printed freely and widely, never received any of the profits, especially from that initial printing in Bell’s paper. Amazingly, Paine was able to stay anonymous for the first three months after Common Sense was published, even though he had a public spat with Bell over the publication.

The pamphlet can be broken down into four main sections; origin and design of government based on the English Constitution, monarch and hereditary succession, thoughts on the current state of American affairs, and the present ability of America, paraphrasing the language used by Paine himself. Paine wrote with a style that was easily readable and relatable, no matter what strata of colonial society one’s station. Paine’s words were read with the power, drama, and vindictiveness, that emanated from the man himself, one who would struggle to harness that spirit at other times in his life. Yet, when funneled, like writing a politically motivated pamphlet, those traits were needed in order to inject emotion and belief, akin to a fresh breath, into the revolutionary movement. For instance, the opening sentences underscore that point and struck a chord with the colonists and reverberated from community to community across the landscape of North America.

“The cause of America is, in a great measure the cause of all mankind. Many circumstances have, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all lovers of mankind are affected, and in the event of which, their affections are interested. The laying a country desolate with fire and sword, declaring war against the natural rights of mankind, and extirpating the defenders thereof from the face of the earth, it is the concern of every man to whom nature hath given the power of feeling; of which class, regardless of party censure is.”

Even Abigail Adams, who received a copy from her husband, was enthralled with the writing style and message Paine put forth. The hopefulness of the opportunity presented by the chance of rebelling against Great Britain was captured in whole, according to Abigail, in the following line.

“We have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again.”

Those two lines above underscored the messaging that Paine was trying to capture in this pamphlet. The chance to begin anew which does not come often, especially in the 18th-century world dominated by monarchs and despotic rulers. This appealed to the masses, the shopkeepers, farmers, and all strata of society, gave voice and a message for a rallying cry around the idea of revolution and change.

Even the top strata of the revolutionary movement stopped to take notice of Common Sense and its far-reaching positive effect. General George Washington, in Massachusetts, took quill to paper to echo Abigail’s sentiments, in a letter to a friend, “I find that Common Sense is working a powerful change there in the minds of many men. Few pamphlets have had so dramatic an effect on political events.”

The lasting effect of this 49-page pamphlet was to put into word and print the argument of why a rupture with Great Britain was not only necessary but as contemporaries and historians would agree, as inevitable. Secondly, Paine gave the reassurance that a victory was also achievable and possible for the colonists, which, without the benefit of hindsight, was a huge endorsement for the fledgling nation tackling the biggest empire currently in the world at that time. All for the hope to garner the “power to begin the world over again.”

Further Readings

- Common Sense By: Thomas Paine

- Common Sense, Rights of Man, and Other Essential Writings of Thomas Paine By: Thomas Paine

- American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804 By: Alan Taylor