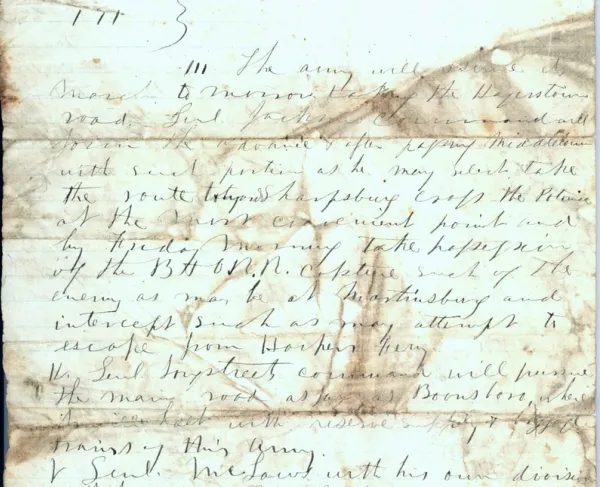

Ten Facts about the vital role of the town of Harpers Ferry in the American Civil War.

Fact #1: George Washington established an armory and arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1794.

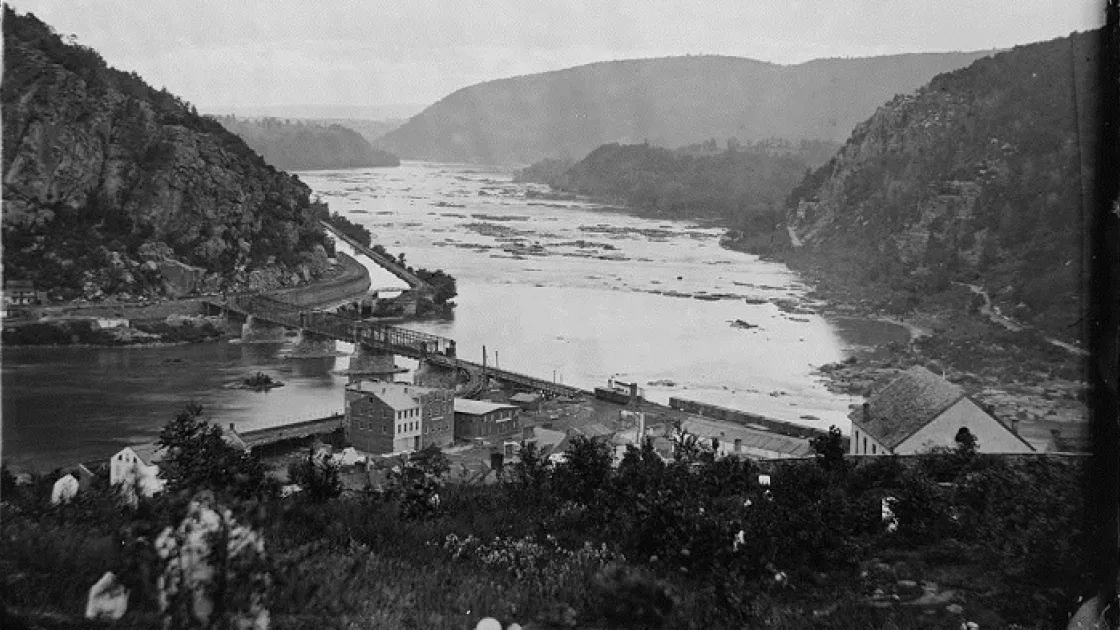

In 1794, George Washington, then a wealthy property owner, visited Harpers Ferry. Impressed by its location at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers and the natural beauty of the town Thomas Jefferson had proclaimed “worth a voyage across the Atlantic for,” Washington selected the town as the site for a new national armory. By 1796, the arsenal was established, and machines shops and rifle works factories brought industry to Harpers Ferry. In the face of its industrial boom, the population of the town grew as Northern merchants, mechanics, and immigrant workers flooded the small western Virginia town. By the 1850s, Harpers Ferry emerged as a significant transportation hub in the east with the building of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Fact #2: Radical abolitionist John Brown raided the Harpers Ferry arsenal in October 1859.

Known for the murder of slaveholders in “Bleeding Kansas,” in 1859 John Brown determined that he would free the slaves in Virginia by instigating a revolt that would spread throughout the slaveholding state. To begin his slave revolt, Brown planned to capture the arsenal at Harpers Ferry and use its cache of weapons to arm his followers. On the night of October 16, 1859, Brown and a company of 21 men—including his sons—occupied the arsenal.

Brown’s raid, however, was doomed from the start. Lacking proper ammunition for his weapons and unable to recruit any slaves to join his rebellion, Brown and his men became trapped in the arsenal as Virginia and Maryland militia surrounded his “fort.” Upon hearing that the infamous “Ossawatomie” Brown had plans for a slave uprising in Virginia, President James Buchanan ordered a company of 90 Marines, led by Col. Robert E. Lee and assisted by Captain J.E.B. Stuart, to put down the rebellion. Upon arriving in Harpers Ferry, Lee ordered the marines to storm the fort, rescue the few hostages Brown had taken earlier in the night (one of which was a relative of President George Washington,) and capture Brown and his men. Brown, severely wounded in the struggle, was hanged on the morning of December 2, setting off a spark throughout the country. To Northern abolitionists, Brown was a martyr to the cause; yet to Southerners, John Brown was a symbol of northern aggression and northern hopes to destroy the Southern way of life.

Fact #3: The day after Virginia seceded from the Union, Federal soldiers burnt the armory and arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

When Virginia voted to secede from the Union on April 17, 1861, the historic arsenal at Harpers Ferry immediately became a target. Former Governor of Virginia Henry A. Wise, the same governor who had hung John Brown for carrying out similar designs on the arsenal, organized a scheme to occupy the valuable armory. Knowing that no arms supplier south of the Mason-Dixon Line could match the output or quality of Harpers Ferry, Wise hoped to raise militia to take the arsenal before the Federal government organized enough troops to hold it. As Virginia militia bands began to assemble not four miles away, a Federal officer stationed in Harpers Ferry, Lieutenant Roger Jones, sent a distressed word to Washington that the armory was in danger and thousands of troops would be required to defend it. When it became clear that Washington was ignoring his request, Jones took matters into his own hands. At 10 p.m. on April 18, Jones and his men set fire to the arsenal, destroying over 15,000 muskets and combustibles in the main armory building, and then retreating across the Potomac Bridge. His efforts were largely in vain, however, as the arsenal was only moderately damaged. With over 4,000 firearms still in usable condition and much machinery able to be salvaged, the surviving elements of the armory were shipped south to Richmond and Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Fact #4: Despite its strategic importance, Harpers Ferry was an indefensible military position.

Harpers Ferry was a strategic nightmare; although it was easy to attack, it was nearly impossible to defend. Surrounded on all sides by the steep rises of Bolivar Heights, Maryland Heights, and Loudoun Heights, successful defense of the town required that the more than one-thousand foot rises towering over Harpers Ferry be posted with artillery. Nestled far below the mountains, the low elevation of the town itself, which led soldiers posted there during the Civil War to describe it as a “godforsaken, stinking hole,” left Harpers Ferry open to attack without much hope for defense.

Fact #5: Between 1861 and 1865, Harpers Ferry changed hands fourteen times.

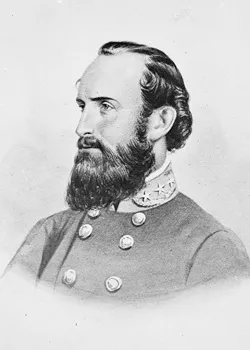

From the beginning of the Civil War until the Union forces permanently reoccupied the town on July 8, 1864, the Harpers Ferry changed hands fourteen times. During the times that it escaped control from either army, the inhabitants of Harpers Ferry remained subject to frequent reconnaissance missions and guerrilla raids. Although no major battle was fought at Harpers Ferry after Stonewall Jackson’s attack on the garrison in 1862, by the end of the Civil War the town was devastated by repeated attempts from both Union and Confederate forces to control the vital transportation hub. Shortly after the war, Harpers Ferry resident Jessie E. Johnson spoke to the instability of Harpers Ferry, writing that “When the Union army came they called the citizens Rebels – when the Confederates came they called them Yankees.”

Fact #6: The largest surrender of United States forces during the Civil War took place at Harpers Ferry.

Although the amount of dead and wounded soldiers was comparatively low after the Battle of Harpers Ferry, the 1862 battle resulted in a staggering number of Federal prisoners – the largest surrender of United States soldiers during the Civil War. When the Federal garrison surrendered on September 15th, 1862, the nearly 12,400 Union troops that had been stationed at the garrison became Confederate prisoners. After being paroled by Gen. A.P. Hill, many of these prisoners were marched to Camp Parole near Annapolis to await their exchange for Confederate prisoners.

Fact #7: During the Civil War, Harpers Ferry became a significant Union army camp, headquarters site, and logistical supply base.

Camp Hill, located on a gentle slope above the town of Harpers Ferry, had been used as a U.S. army encampment in the late 18th century, and had since been populated with spacious mansions reserved for armory officials. When the Civil War broke out, however, these mansions were immediately converted into headquarters and hospitals; Camp Hill became an army camp once more. In the spring of 1861, the Confederate army occupied the camp, but quickly abandoned it under orders from the garrison commander Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. Soon afterward, it was occupied by infantrymen from the 2nd Massachusetts. Having been fortified by both Union and Confederate troops and naturally protected by steep banks, Camp Hill served a natural defensive position that aided the Union troops during the Stonewall Jackson’s attack on Harpers Ferry in September 1862. Although the garrison surrendered after Jackson’s attack, on September 24, nine days after the battle, the Army of the Potomac marched to Harpers Ferry and pitched their tents once more on Camp Hill and neighboring Bolivar Heights, where they remained immobile until November. Later, during Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Shenandoah Campaign, “Little Phil” made his headquarters in a home on Camp Hill.

Fact #8: St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church in Harpers Ferry flew a British flag to avoid destruction during the conflict.

During the Civil War, the Reverend of St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church, Father Michael Costello, avoided damage to the church throughout repeated artillery bombardments and contests for the town by flying a British flag over the church. Despite the debilitating damage sustained by other buildings nearby throughout the Battle of Harpers Ferry and repeated artillery bombardments in the summers of 1863 and 1864, St. Peter’s went unharmed as a result of its supposed British affiliation. As it remained intact during the war, St. Peter’s was frequently used as a makeshift hospital, and Costello continued to administer sacraments and hold services throughout the war. St. Peter’s remained the only church in the war ravaged town of Harpers Ferry that was not severely damaged or destroyed by Northern or Southern forces.

Fact #9: A cavern just outside Harper's Ferry served as a hiding place for Confederate guerrilla raiders throughout the war.

In November of 1864, in the midst of Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley campaign, Sheridan’s men became perplexed at Confederate partisan ranger Col. John Singleton Mosby’s ability to avoid detection and capture by disappearing from his pursuers. While scouting for guerrillas, a Federal cavalryman accidentally made a shocking discovery just outside Harpers Ferry when he fell through a trapdoor in the floor of a burned and abandoned building. Beneath the trapdoor lay a tunnel leading to a stairway deep underground. Returning with a scouting party, the Federals descended the staircase into a cavern that they estimated was large enough to hold three hundred horses. There was only one opening into the room, a space so narrow that only one horse could enter at a time, and only after wading through three feet of water. The entry was covered by brush and rocks, and was marked by a high cliff to mark the hideout. The room, they quickly realized, belonged to Col. Mosby and his band of rangers, allowing them to evade capture by Federal forces.

Fact #10: The Civil War Trust has saved hundreds of acres of land Harpers Ferry.

Harpers Ferry today has remained remarkably well preserved. The National Park Service has preserved the majority of the battlefield at Harpers Ferry, yet there are still significant pieces of the battlefield that remain threatened by development. In 2002, the American Battlefield Trust successfully saved 325 acres of endangered land at Harpers Ferry, and in 2013 saved an essential tract of battlefield land on Bolivar Heights.

Learn More: Maryland Campaign

Related Battles

12,636

286