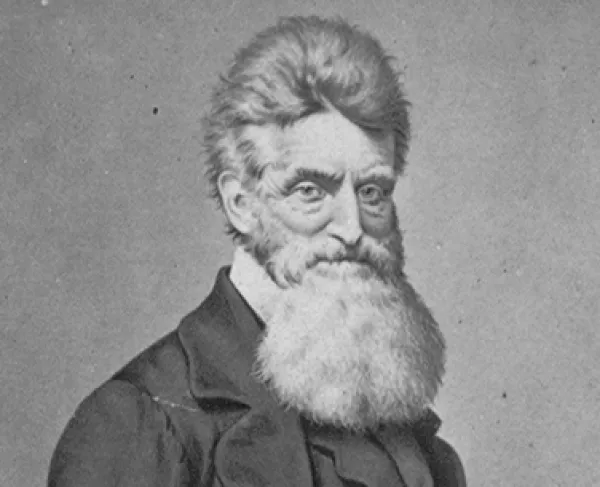

John Brown

Born in Torrington, Connecticut, John Brown belonged to a devout family with extreme anti-slavery views. He married twice and fathered twenty children. The expanding family moved with Brown throughout his travels, residing in Ohio, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and New York.

Brown failed at several business ventures before declaring bankruptcy in 1842. Still, he was able to support the abolitionist cause by becoming a conductor on the Underground Railroad and by establishing the League of Gileadites, an organization established to help runaway slaves escape to Canada. In 1849, Brown moved to the free black farming community of North Elba, New York.

At the age of 55, Brown moved with his sons to Kansas Territory. In response to the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas, John Brown led a small band of men to Pottawatomie Creek on May 24, 1856. The men dragged five unarmed men and boys, believed to be slavery proponents, from their homes and brutally murdered them. Afterwards, Brown raided Missouri – freeing eleven slaves and killing the slave owner.

Following the events in Kansas, Brown spent two and a half years traveling throughout New England, raising money to bring his anti-slavery war to the South. In 1859, John Brown, under the alias Isaac Smith, rented the Kennedy Farmhouse, four miles north of Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). At the farm Brown trained his 21 man army and planned their capture of the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Part of the plan included providing slaves in the area with weapons of pikes and rifles. Brown believed that these armed slaves would then join his army and free even more slaves as they fanned southward along the Appalachian Mountains. If the plan worked it would strike terror in the hearts of slave owners.

On October 16, 1859, John Brown and his men raided the Federal Arsenal. Unfortunately for Brown, nothing went as planned. Slaves living in the area did not join the raid, local militia and the United States Marines, under Robert E. Lee, put down the raid, and most of John Brown’s men were either killed or captured, including two of his sons. Ironically, the first man killed during the raid was Hayward Shepherd, a free black man working with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Despite being seriously wounded, Brown was tried quickly and found guilty of murder, inciting slave insurrection, and treason against the state of Virginia.

Upon hearing his sentence, Brown said,

“…if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments--I submit; so let it be done!”

Brown told the court that he had hoped to carry out his plans “without the snapping of a gun on either side.” But Brown’s vision of ending slavery was marred by the deaths of innocent civilians – both in Kansas and at Harpers Ferry. The nation was divided over his actions. Many abolitionists called him a hero. Slaveholders called him a base villain. People on both sides of the fence denounced Brown’s use of violence.

John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859. Before he died, Brown issued these final, seemingly prophetic words in a note he handed to his jailer:

“Charlestown, Va, 2nd, December, 1859

I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.”

Within one year, the first Southern state would secede from the Union.