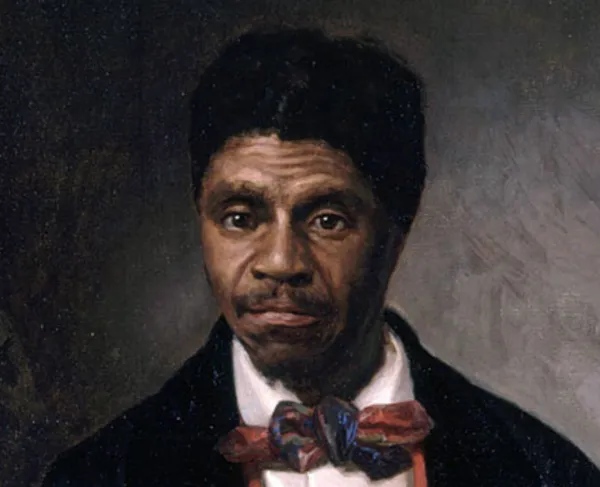

Dred Scott

A man who “lived all but two of his sixty-odd years in obscurity,” Dred Scott was born into slavery in Southampton, Virginia, around 1799. Dred Scott was owned by Peter Blow, who moved to Huntsville, Alabama and took Scott with him. After an unsuccessful farming venture, Blow moved to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1830. Blow died in 1832, and Scott was bought by a United States Army Surgeon, Dr. John Emerson.

In late 1833, Emerson moved to Fort Armstrong in Illinois, a free state, and took Scott with him. In 1836, Emerson was transferred to Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory (present-day Minnesota). In 1820, the Missouri Compromise banned slavery in the land included in the Louisiana Purchase north of the latitude line 36°30’, with the exception of Missouri itself. Despite this, Scott remained enslaved during his time at Fort Snelling. While there, he met and married Harriet Robinson, an enslaved woman owned by Major Lawrence Taliaferro (pronounced Toliver), the local Indian agent. Together they had two daughters, Eliza in 1838, and Lizzie in 1840.

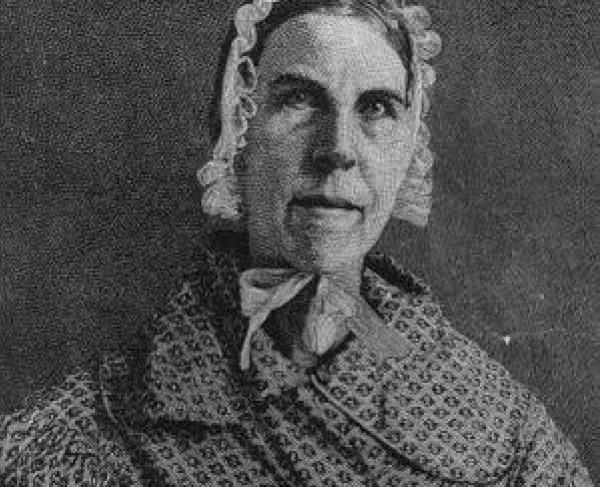

Emerson was transferred again to Fort Jesup in Louisiana where he married Eliza Irene Sanford. When Emerson was sent to fight in the Seminole War in Florida, the Scotts stayed in St. Louis with his wife. John Emerson suddenly died in 1843 and his entire estate, including the Scotts, was left to his widow. The widow Sanford hired out the Scotts’ services to various people for the next three years.

Scott had spent a considerable part of his life in free territory. His stays in Illinois and then Wisconsin gave him legal standing to sue for freedom, but for uncertain reasons, he chose not to do so. It was only in 1846 that Scott offered to purchase his freedom for $300 from Sanford. She refused, so Scott turned to the courts for freedom.

Scott’s case would traverse the American legal system in a circuitous route before finally reaching the United States Supreme Court. He enlisted the support of two St. Louis attorneys and took the case to the St. Louis circuit court; he lost on a technicality. Three years later, with direction from the Missouri Supreme Court, the St. Louis circuit court retried the case, and this time, they ruled that Scott and his family had been held illegally as slaves and were free. After two years of freedom, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the St. Louis court’s decision, and the Scotts had to be returned to Sanford. Scott then appealed this decision to the U.S. Circuit Court in Missouri, but it only upheld the lower court’s decision; Scott’s family was still property of Sanford. With nowhere else to turn, Scott and his lawyers appealed this decision to the highest court in the land: The Supreme Court.

On March 6, 1857, in a 7-2 ruling by a largely Southern majority, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney handed down a decision that destroyed Scott’s last hope for freedom and would send shockwaves through an already divided nation. With pressure from President James Buchanan, the majority ruled that any person of African descent in the U.S. –whether enslaved or free—were not citizens, and thus Scott had no right to sue in federal court. The majority of Justices justified their claim, stating:

“We think ... that [black people] are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States. On the contrary, they were at that time [of America's founding] considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.”

Although Scott had already clearly lost, Taney went further and wrote that the federal government had no power to ban slavery in the territories of the United States and thus the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. What has been seen as a constitutional sanction to slavery enraged Northerners and pleased many Southerners, while heightening the divisions of a nation on the verge of civil war.

After the ruling, Sanford returned ownership of the Scotts to the Blow family, who granted the Scotts their long-awaited freedom. They stayed in St. Louis, where Harriet worked as a laundress and Dred worked as a porter in a hotel. He died of tuberculosis on September 17, 1858, exactly four years before the Battle of Antietam would compel Lincoln to issue his Emancipation Proclamation.