What Might Have Been: Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

There is no better way to get an accurate sense of what the Trust has accomplished in the last 30 years than by examining sites that could have been lost but that are now saved forever.

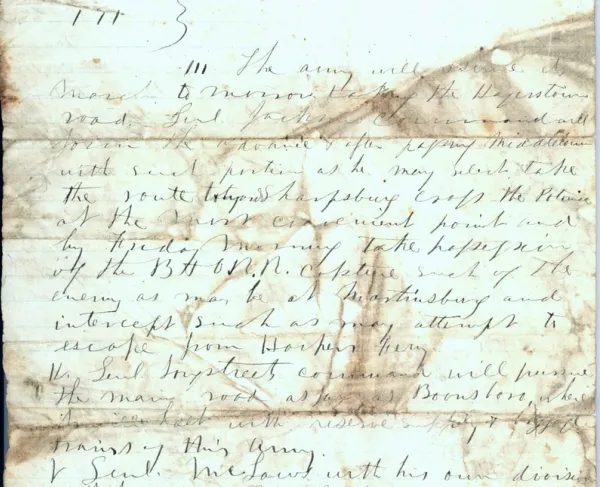

The story of preservation at Harpers Ferry — scene of militant abolitionist John Brown’s 1859 raid and an 1862 siege and battle that resulted in the largest surrender of U.S. Army personnel until the 1942 fall of Corregidor in the Philippines — has been full of dramatic highs and lows. The process began in 1992, when the original Civil War Trust worked with the National Parks Trust and the Jefferson Security Bank to purchase 56 acres along the Federal skirmish line. Then, in 2002, the Trust received federal matching funds from the American Battlefield Protection Program and the Transportation Enhancement program to purchase 232 acres on School House Ridge — land subsequently transferred to Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

These were important projects with high price tags, but they were accomplished with relatively little drama or fanfare. That changed beginning in 2005, when the Trust purchased the 37-acre Perry Orchard property on the south side of Route 340, west of the entrance to the park’s main visitor center, and transferred it to the park. A utility easement had previously been placed on the land, however, and a year later, developers secretly laid water and sewer pipes through the land without permits or other authorization, hoping to encourage a rezoning for development on other nearby parcels. The preservation community rallied against the desecration and has thwarted all attempts to make use of the illicit pipes.

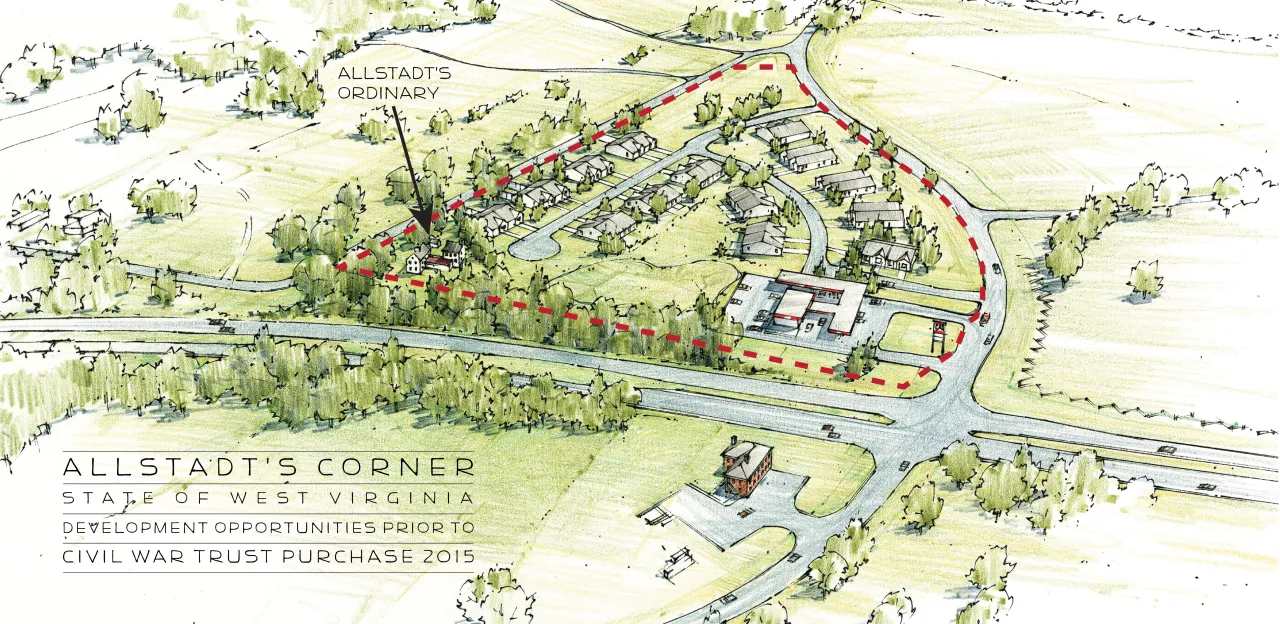

Yet an even greater threat simmered on the adjacent property, home to the Allstadt Ordinary, the front door of which was kicked in by Brown’s raiders and whose occupants were taken hostage by them. Set back as it was from the road, few visitors ever saw the historic structure, which still bore the scars of history, but many were familiar with the weekend flea market held on the property. Prior to July 2009, very limited uses were permitted for the property — the weekend market and a few apartments carved out of the historic house and ordinary. That changed in July, when it was rezoned for up to 54 high-density residential units. Another rezoning in August 2013 permitted a six-lot business park subdivision on one portion of the 13-acre property, while retaining the Allstadt’s Ordinary building and cemetery on four acres. The threat for this type of major development intensified in January 2014, when a stoplight was installed at the adjacent intersection.

The Trust rejected the opportunity to purchase just the historic four acres, believing that the proposed adjacent development would undermine the surrounding integrity of the site. Instead, the organization structured the $2.5 million transaction to make use of a matching grant from the American Battlefield Protection Program and funding from a major donor and Trust members to permanently protect the entire property forever.

More in "What Might Have Been" series:

Related Battles

12,636

286