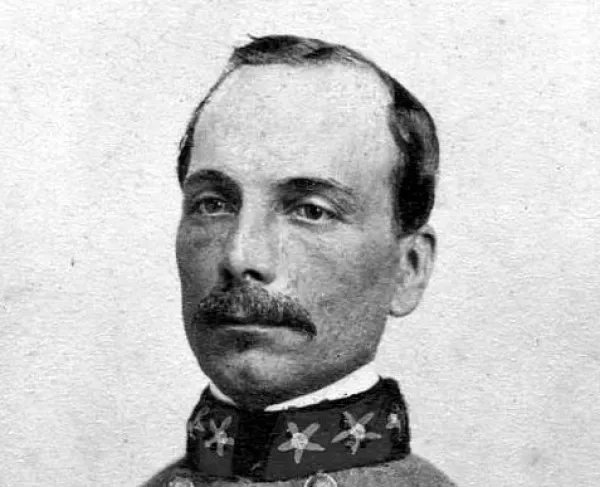

Juan de Miralles

Juan de Miralles—a wealthy Spanish merchant and secret envoy—forged diplomatic ties between the United States and the Spanish Crown, securing important aid during the American Revolution. His unique position, intelligence gathering, and personal relationships with George Washington highlight Spain's involvement in the Revolution.

Juan de Miralles was born in 1713 in Preter, Alicante, Spain. By age 19, he worked for the Aguirre, Aristegui and Company, a large Spanish firm which traded with the British colonies in North America and monopolized the Spanish slave trade in Cuba. Miralles built a successful career as a merchant and became part of a commercial network on both sides of the Atlantic. He learned English and spoke the language fluently, a helpful skill for trading with the British Colonies. He settled in Cuba and married Maria Josefa de la Puente. Together, they had eight children, one son and seven daughters. By the outbreak of the American Revolution in the British Colonies in 1775, Miralles was a man of wealth and connections, traits that would prove important during the conflict.

In November 1777, José de Gálvez, the Spanish Minister of the Indies, appointed Miralles as a secret representative to the Continental Congress. As a private merchant, he could travel and establish contacts without revealing his diplomatic purpose. His mission required care and delicate diplomacy; Spain wanted to weaken its global rival, Britain, but was wary of openly supporting a colonial revolt that might inspire similar uprisings in its own empire.

In 1778, Miralles arrived and established himself in Philadelphia, following the American reoccupation of the city. He served as a spy and gathered intelligence on British military movements and assessed the American war effort. He also helped coordinate Spanish aid to the Americans, even though Spain had not officially joined the war. Miralles quickly immersed himself in American society, using his fortune to host parties and cultivate relationships with influential figures. He developed a friendship with George Washington, frequently writing letters and meeting the general several times at military headquarters. Washington valued Miralles's insights and ability to provide information on European and Spanish affairs. Miralles also interacted with members of the Continental Congress, including Edward Rutledge, Patrick Henry, and Robert Morris.

Operating through business associates, ship captains, and merchant networks, Miralles established an extensive intelligence network that monitored British activity from the Caribbean to North America. He sent detailed reports to the Spanish Captain General in Cuba. More significantly, he coordinated Spanish aid to the Patriots. This included materials such as arms, uniforms, gunpowder, bayonet rifles, flour, sugar, and quinine, a medicine to combat disease. Through his efforts, Spain provided significant financial support, including loans of 40,600 pesos to South Carolina and a substantial 140,650 pesos to the Continental Congress. He even sent guavas and limes to combat scurvy among American troops.

Miralles's diplomatic efforts helped to coordinate military strategy. He advised Congress on how aid from Bernardo de Gálvez, the governor of Spanish Louisiana, could be channeled through figures like Oliver Pollock. He also planned with American leaders, including General Benjamin Lincoln, about potential combined French-Spanish-American operations against British forces.

Tragically, Juan de Miralles died of pneumonia on April 28, 1780, while visiting George Washington's headquarters in Morristown, New Jersey. Washington led the funeral procession, a testament to the respect and friendship for the Spanish envoy. His death was a significant loss for the American cause and future United States-Spain relations. Historians suggest that his successors could not replicate the unique relationships Miralles established with American leaders.

Though often overshadowed by other prominent figures, Juan de Miralles had a key role during the American Revolution. His dedication and diplomatic skill secured Spanish aid that contributed to American independence.