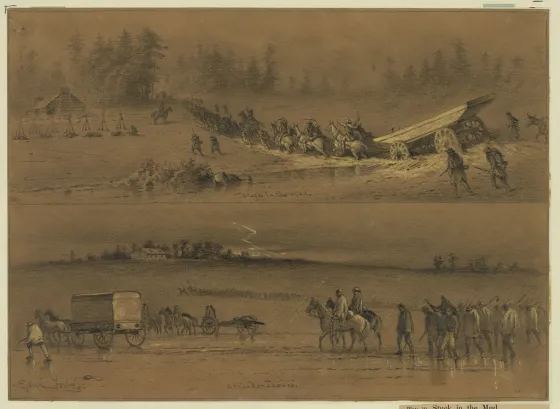

"Dragging Artillery Through the Mud" in Harper's Weekly

Weather operates beyond the control of politicians, military leaders, soldiers, and civilians. Despite efforts of Civil War-era Americans to overcome rain, snow, wind, and heat, these elements set real limits to how armies moved, how crops flourished or failed, how transportation worked or did not work, and how soldiers and civilians felt in the elements. In an event that took place largely outdoors, the outdoors played a critical role in shaping the nation’s critical conflict.

The most famous weather impact of the war was Burnside’s Mud March in January 1863. Though started in reasonable weather, a strong storm with numbing temperatures, howling wind, and heavy precipitation bogged down a bold plan and led to dramatic and demoralizing failure. But the list of campaigns determined by weather is long. Heavy rain slowed George McClellan’s Spring advance up the Virginia Peninsula. Dry weather and heat had helped stop Don Carlos Buell’s advance through North Alabama toward Chattanooga in the summer of 1862. William T. Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant encountered heavy rain and flooding that stymied two attempts to capture Vicksburg in late 1862 and early 1863. Unusually wet weather in Virginia in Spring 1863 hindered Joseph Hooker’s rejuvenation of the Army of the Potomac and made chaos out of the army’s initial offensive moves in April 1863.

On the Confederate side, the situation was the same. Stonewall Jackson’s Bath-Romney Campaign in January 1862 ground to a halt because of numbing cold, icy roads, and a blizzard. Heavy rain, fog, flooding, and mud thwarted the Confederates at the Battle of Mill Springs, Kentucky, on January 19, 1862. Bad water and drought limited Braxton Bragg’s army in northern Mississippi in the spring and summer of 1862. After Gettysburg, the deluge that soaked the defeated soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia led to the rapid rise of the Potomac River and imperiled Robert E. Lee’s escape into Virginia. Soldiers in James Longstreet’s First Corps suffered through a miserable winter near Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1863-1864 as rain, cold, and snow limited movement. In late 1864, John Bell Hood’s Tennessee Campaign collapsed in the face of fierce winter weather including snow, ice, fog (that helped George Thomas conceal his preparations for smashing attacks on December 15 and 16) and freezing rain that helped shred unit cohesion in the rebel ranks.

Across the nation and through the entire war, weather played an outsized role in how the armies moved or did not move. Indeed, officers and soldiers from both sides had occasion to declare, as did Rice Bull of the 123rd New York Infantry at the conclusion of the Battle of Chancellorsville “it seemed that all nature had conspired against us.”

But bad weather affected other aspects of both the United States' and Confederate States' war efforts. Drought, frost, and heavy rain interrupted planting seasons, destroyed crops in the field, and dramatically impacted crop yields across the North American continent. As historian Kenneth Noe has pointed out, perhaps one of the most under-appreciated events of the Civil War was the 1862 drought that destroyed crops across the Confederacy. The failure set off a cascade of consequences that created short and long-term problems for the Confederacy. That auspicious weather conditions led to excellent harvests in the north at the same time made the southern crop failure even more acute.

Weather impacted morale as well. Soldiers in the field endured extreme cold, deep mud, rain and snow, stifling heat and dust that made simply breathing difficult. Both on the march and in camp, weather conditions could brighten or darken soldier’s dedication to their respective cause. Civilians suffered as well. This was particularly true In the Confederacy where the drought fueled crop failures of 1862 led the Richmond government to impose some of its most unpopular policies – impressment – that caused many to become enemies of the Confederate government.

The same crop failures laid the foundation for civil unrest in Richmond where thousands of women rioted over steep food prices and shortages in April 1863 and led many rebel soldiers to leave the ranks to help desperate and starving families at home. The famine’s impact was perhaps most poignantly expressed in “The Widow’s Appeal” that appeared in the Athens Southern Watchman on April 3, 1863. “Stranger have you corn? Can you my wants supply? My infant, early born, Needs succor, or else’ twill die.”

While many Civil War-era Americans held to a whiggish view that human agency could overcome nature, the experience of the war-years showed clearly that some conditions of climate and weather simply defied human agency. By thinking about how the weather shaped the ways people acted, how they struggled, and how they bent to the will of nature helps us to better understand the friction of war in its fullest sense – both on the field of action and on the home-front.

Further Reading:

- War Upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of the Southern Landscape During the Civil War By: Lisa M. Brady.

- The Blue, The Gray, and the Green: Toward an Environmental History of the Civil War By: Brian Allen Drake.

- The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States By: Mark Fiege.

- The Howling Storm: Weather, Climate, and the American Civil War By: Kenneth Noe.

- Nature's Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia By: Kathryn Shively.

- "'The Women Rising': How Cotton, Class, and Confederate Georgia's Rioting Women" By: Teresa Crisp Williams and David Williams in The Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 86, No. 1 (Spring 2002), pp. 49-83.