Purple Heart and Medal of Honor Recipient Jack Jacobs On Courage, Service and Sacrifice

Vietnam War Purple Heart and Medal of Honor recipient Jack Jacobs reflects about the shared experience of soldiers across time.

I

grew up in New York City during the 1950s, in the projects of Queens. Every household had made some contribution to the defense of the Republic. It was unusual to find someone who had not served, actually. I had friends who had fathers with parts missing. I had friends who had no fathers, because those fathers had made a sacrifice to save the world. Now it’s exactly the opposite; most Americans do not know anyone in uniform. In an environment in which very few people serve it becomes something of a movie to most people. It looks like a fiction because you haven’t had that experience. And so our views about what service and sacrifice are have been skewed by a lack of knowledge.

My father was drafted into the Army in the Second World War, and was not very pleased about being pulled out of the University of Minnesota just before he finished to go fight in the South Pacific. And yet when he was my age, all he talked about was how proud he was to have served the country. The same thing is true of people of my generation — about 40-45 percent of the people who served in Vietnam were drafted, many of them dragged kicking and screaming into uniform. Go talk to them now that they’re 70 or 75 years old: There is nothing that they are prouder of than having served.

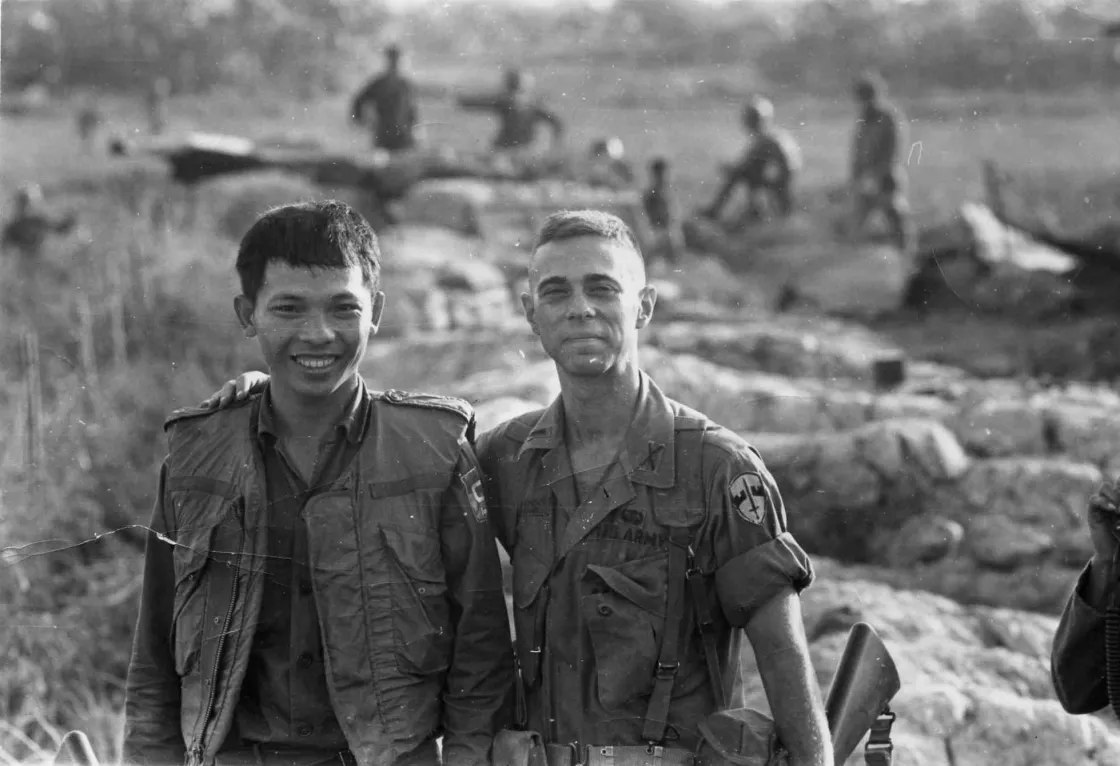

That experience of having been young and in uniform is transformative. Which war you served in is irrelevant. It’s a bond that is impossible to break, and I think it becomes stronger over time. You’re way from home, burdened with large authority and responsibility. You know the mission itself is important, but you’re in miserable circumstances — too cold, too hot, too hungry, too thirsty, too tired. I think the experience is generally unpleasant but the people you go through it with make it bearable. Different weapons different tactics, different intensity, but the experience of being in combat, being in fear for your life, having to perform missions that were really important, taking care of each other, remained the same.

I don’t think you can judge valor with any kind of regularity or equitability. It’s a subjective evaluation, despite the fact that the services have tried to judge it in absolute or relative terms. Is this worth a Medal of Honor or a Distinguished Service Cross? A Service Cross or a Silver Star? And I think military people have grappled with this for a long time which is why there was originally only the Purple Heart. You either did something valorous or you did not. It makes it more equitable but also more inequitable once you start instituting gradations of valor.

Lots of people received Purple Hearts who are not around to talk about their experience, because it killed them. And those of us who are still here, when asked about the circumstances of our award, often give it short shrift, preferring instead to remember a buddy who did not survive, perhaps killed in the same incident. We know that it was originally an award for military merit, but that it was transformed into an award that signifies sacrifice. It’s about more than our own sacrifice, it’s about those who sacrificed but didn’t survive to wear the medal. There’s some survivor’s guilt there, obviously.

But it’s more than own own sacrifice, it’s about those who sacrificed but didn’t survive to wear the medal.

As for my own action, the enemy had spies in the province headquarters. So they knew we were coming; they had three days to set up an ambush, and we walked right into it. We lost a large number killed and wounded in the first seconds of the battle, including me. There were a lot of other soldiers who were out in the open. I was badly wounded too, but I was the only person who was in a position to do something. I thought it was my obligation to do what I could to get them out of there. So I went out and dragged some of them back, carried some of them back. The Viet Cong were coming out of their bunkers with supporting cover, taking the weapons from our dead and shooting the wounded. I did that until I ran out of gas; I sat down to catch my breath and I couldn’t get up again because I’d lost too much blood.

A citation is like a photograph; it’s a snapshot in time and doesn’t tell the whole story. Mine doesn’t mention how scared I was. But it’s interesting about fear. A great calm comes over you in a circumstance in which you not only might not survive, but in which you are likely not to survive. And you are much more relaxed about it all. It’s not that you aren’t scared anymore, but that it doesn’t matter anymore. The other thing about fear is that it gets you to do things you otherwise wouldn’t do. There’s a lot of adrenaline that is attendant to being scared and that gives you strength you otherwise wouldn’t have. I talk to cadets often about fear in combat and I tell them I rarely saw fear immobilize people; fear usually did exactly the opposite. It motivated people to take care of each other and do positive, valiant things they otherwise wouldn’t do.

I feel a tremendous connection to Medal of Honor and Purple Heart recipients from the past — in no small part because I met a lot of them! At the first Medal of Honor dinner I attended, one of the people there was a guy named Bill Seach, who had conducted a bayonet charge against the citadel in Bejing in 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion. There were almost 400 living recipients of the Medal of Honor then, and it was like talking to history. World War I fighter ace Eddie Rickenbacker sat at my table. I was 24, and living legend Jimmy Doolittle put his arm around me. “Congratulations young man,” he said. “You are no longer Jack Jacobs. You are Jack Jacobs: Medal of Honor Recipient, and you had better comport yourself accordingly.” He had a good point: I don’t represent me, I represent all of those who are not here any longer, whether because they fought in a long ago war, or because their situation was such that they didn’t survive.