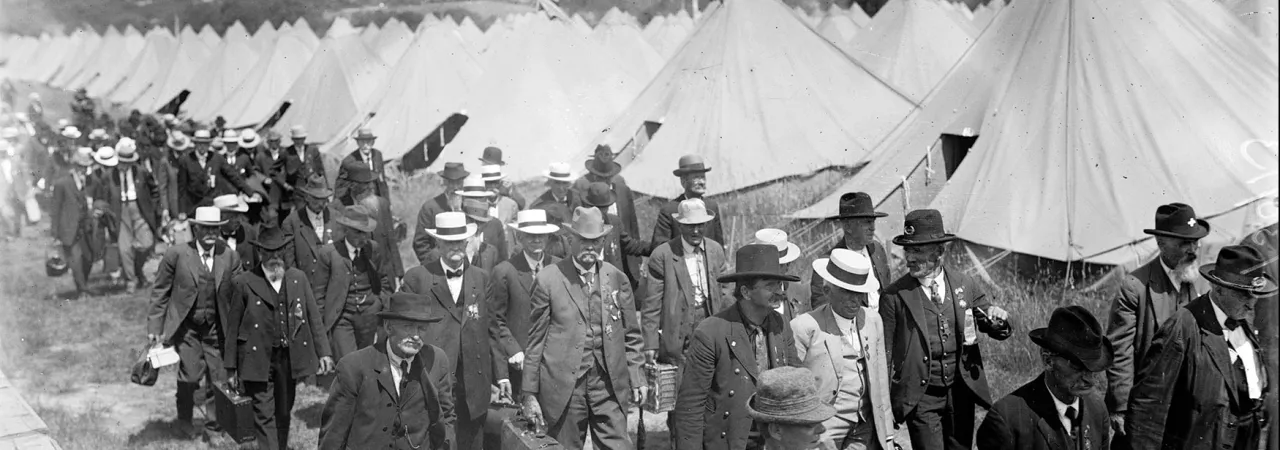

More than 53,000 veterans travelled from 46 of the 48 states to attend the reunion. Many received travel stipends from local/state commissions and individual donors to attend.

Undeterred by the same heat they remembered from 50 years earlier, more than 53,000 veterans, accompanied by vast numbers of support personnel and spectators, descended on Gettysburg in early July 1913. The four-day event — incidentally the largest tent gathering since the Civil War — sparked massive media coverage and drew interest from coast to coast.

Momentum for a massive gathering on the fields of Gettysburg to mark the milestone grew out of smaller reunion events held by the Grand Army of the Republic and the United Confederate Veterans. In 1906, when Union veterans from the Philadelphia Brigade and Confederates from Pickett’s division met at Gettysburg in reconciliation, the captured sword of Confederate Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead was returned as a token of good will.

Leaders from both organizations met with Gov. Edwin Sydney Stuart, the Gettysburg National Park Commission and local officials to draw up a proposal for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. These initial efforts resulted in the formation of the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg Commission; its $1.2-million budget coming primarily from the States of Pennsylvania and New York and the U.S. War Department. With the U.S. Army, the Gettysburg National Park Commission and the town of Gettysburg tapped to act as cohosts, planning began in earnest in August 1912.

The War Department drew up plans for a Great Camp of more than 5,000 tents spread across 280 acres along Long Lane and the Bliss Farm. Notable features included: a 13,000-person Great Tent designed as a central site for programming; distinct lodging areas for Union and Confederate veterans, with streets organized by state; mess tents, where 2,170 cooks prepared more than 680,000 meals; Pennsylvania Health Department latrines with a “seating capacity” of more than 3,000; temporary outposts for a U.S. Post Office; and, given the age of participants, a medical examiner’s morgue.

In addition to the vast tent city, significant support services were required across the battlefield and throughout the community. To boost capacity, the local railroad built a special platform for veterans to disembark from trains directly into the camp. The Pennsylvania Health Department set up a field hospital at the north foot of East Cemetery Hill, while the American Red Cross and Boy Scouts manned 14 first aid stations. Six “comfort stations” were set up throughout the area with a total of 100 bathrooms. Some 400 Boy Scouts were enlisted to act as escorts for aged veterans, and a battery of the Third U.S. Field Artillery and several companies of Regular Infantry were attached to the Great Camp. With such a crowd, security was a concern, so 285 officers and men of the 15th U.S. Cavalry acted as battlefield guards, and four squads of Pennsylvania State Police were brought in for law enforcement.

In anticipation of the reunion, the Pennsylvania Planning Commission completed the Pennsylvania Monument on the battlefield and mailed 40,000 invitations to surviving veterans. Following the announcement that President Woodrow Wilson would speak, the event became a national sensation, prompting creation of a “Newspaper Row” with housing for 155 journalists. The Newton Enterprise from North Carolina exclaimed that “This Reunion will mark an epoch in history, no such thing having ever been heard of before.” The Philadelphia Inquirer noted on June 11, “It is going to be a noble celebration from many points of view, but the human interest is certain to be the greatest.”

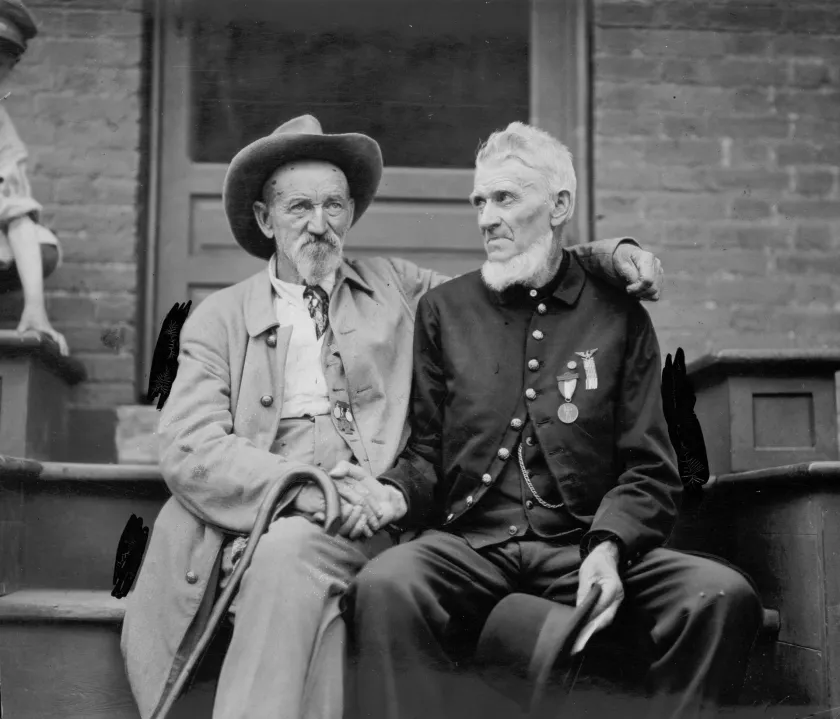

“They forgave each other; they served each other; they laughed and sang together, and in that moment, beginning within each of their hearts, they shone as bright examples to a nation still divided by the bitter division of Civil War.”

E. Urner Goodman, 22-year-old Scout master at the reunion

Ultimately, more than 53,000 veterans represented all but two of the 48 states (the exceptions being Nevada and Wyoming). Many couldn’t afford the trip and received support from national, state and local donations. The more-robust-than-anticipated attendance overwhelmed available resources, and many veterans noted a shortage of tents and food.

Each of the four days had a theme with official events scheduled. Noted philanthropist John Wanamaker highlighted Veterans’ Day on July 1. On July 2, Military Day, an array of speakers recommended a stronger military in this period of increasing tensions in Europe. A reading of the Gettysburg Address and a review of the Virginia division at Seminary Ridge also were noted events. That evening, an impromptu Union raid on the Confederate side of the Great Camp resulted in joint parades and campfires.

July 3, being Civic Day, marked some of the most notable events of the reunion. There were 65 unit-specific reunions, various speeches by dignitaries and a fireworks display that covered the face and crest of Little Round Top. Additionally, in what would later become the signature event of the reunion, George Pickett’s and Alexander Webb’s divisions met along a stone wall at the Bloody Angle on the hour of Pickett's Charge for a formal flag ceremony.

The last day of the event, being National Day, saw President Wilson share a keynote address in which he summarized the spirit of reconciliation. “We have found one another again as brothers and comrades in arms, enemies no longer, generous friends rather, our battles long past, the quarrel forgotten — except that we shall not forget the splendid valor.”

Related Battles

23,049

28,063