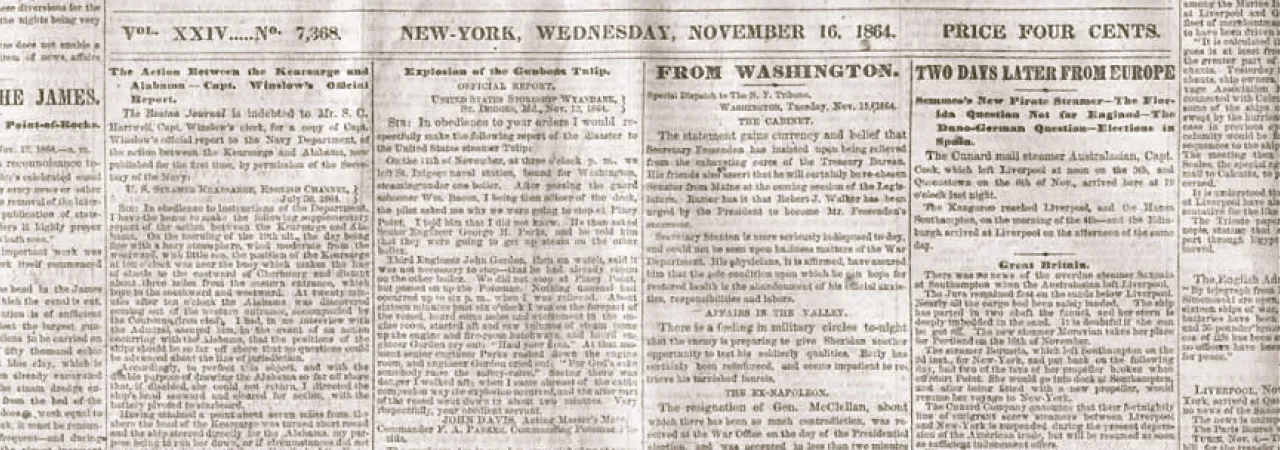

An 1864 issue of the New York Tribune.

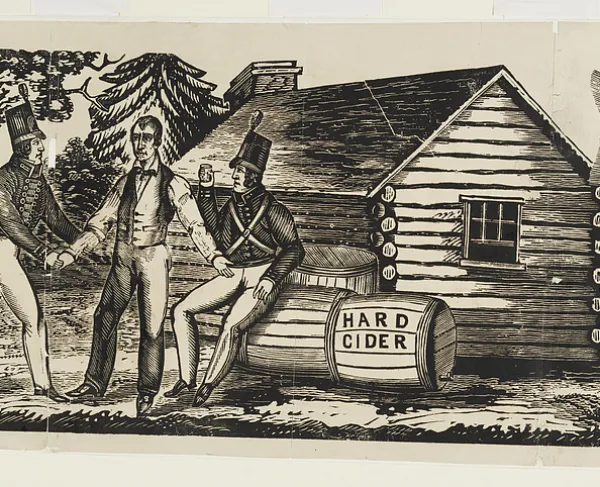

Founded by Northern publisher and political firebrand Horace Greeley in 1841, the New York Tribune originally bore the name New York Daily Tribune. Greeley merged two of his previous publications—a weekly newspaper known as The New Yorker and the Whig Party paper Log Cabin—to form a new daily devoted to social and political commentary. In its early days, the New York Daily Tribune championed liberal reforms, including pacifism and feminism, as well as advocated for the working class in its widely read and distributed editorials.

The Tribune hosted an array of writers including Margaret Fuller, Julius Chambers, Charles Anderson Dana, and The New York Times founder, Henry Jarvis Raymond. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels served as the paper’s European correspondents before the Civil War. The Tribune grew to reflect Greeley’s opposition to liquor, tobacco, gambling, capital-punishment, and most of all—slavery. In 1854, Greeley aligned the paper with the fledgling Republican party and its commitment to preventing slavery’s expansion. On the eve of the Civil War, the Tribune boasted a readership of nearly 300,000 subscribers from Maine to California, making it the largest daily publication in New York City. By that time, newspapers across the country republished the Tribune’s editorials, helping to shape national public opinion. Greeley and his journalists supported the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1861 and denounced the subsequent secession of the Southern states. As the war persisted, the Tribune continued to support the causes of preserving the Union and the abolition of slavery.

However, Greeley chided the initial hesitancy with which the president and his generals pursued the Confederate armies, particularly General George B. McClellan. The anti-slavery editor blamed much of the Union army’s military ineptitude on pro-slavery officers like General Robert Patterson. The Tribune widely publicized Patterson’s failure to prevent General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate army from rendezvousing with General P.G.T. Beauregard’s forces to defeat Union General Irvin McDowell in the First Battle of Bull Run. Following McClellan’s removal after the Battle of Antietam, Greeley next targeted General in Chief Henry Halleck as a pro-slavery Democrat and source of the Union’s military deficiencies. Greeley openly criticized the “West Point element” of the army for displacing anti-slavery officers like General John C. Frémont and General Franz Sigel. The Rebels should be crushed “in blood and fire if necessary,” condemned the Tribune in 1861. The publication also publicly critiqued the president’s calculated appeasement of the border states, which Greeley believed should be occupied by Federal armies and their citizens branded as traitors.

In 1862, Greeley and his managing editor Charles A. Dana began to differ regarding military operations and proper conduct the Union army. Dana tendered his resignation and went to serve in the war department where he acted as a liaison between Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and General Ulysses S. Grant. The Tribune remained critical of Union strategy through much 1862 and 1863 and argued the North should rely more upon its superior numbers. Some columnists even advanced a plan which called Lincoln to summon all the Union troops in Maryland and Washington to reinforce the Army of the Potomac in an irresistible attack on Richmond. In light of successes at Gettysburg and Chattanooga, the Tribune reversed its pessimistic tone and predicted total Union victory in the war by the following May. “For the first time,” the publication proclaimed, “the Rebellion visibly totters to its fall and the victories of the Union approach their consummation.” Though the war did not end in 1864, the Tribune wholeheartedly praised Grant’s aggressive pursuit of General Robert E. Lee in the Overland Campaign.

Throughout the war, Greeley ensured the Tribune maintained its criticism of the Democratic party. The publisher soon drew the nation’s ire when he publicly praised Lincoln’s first national conscription act in 1863. As a result, a mob of mostly Irish working-class men attempted to set fire to the Tribune headquarters during the New York City draft riots. Though the Tribune clung to Republican party ideals, it did not endorse Lincoln in the presidential election of 1864 until the fall of Atlanta. Greeley simply lacked faith in Lincoln’s ability to end the war and successfully put down the rebellion. However, Greeley’s reluctantly renewed his support of Lincoln when other Republican candidates failed to challenge the president and Union General William Tecumseh Sherman captured the Confederate stronghold of Atlanta.

Following the Civil War, Greeley and the Tribune continued to support the Republican party and its Reconstruction policies. In accordance with the publisher's own convictions, the paper largely condemned President Andrew Johnson and heralded the efforts of Radical Republicans like Representative Thaddeus Stevens and Senators Charles Sumner and Benjamin Wade. However, Greeley broke his newspaper's ties with the Republicans during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. He believed the party had grown corrupt and their Reconstruction efforts no longer necessary.

After Greeley’s failed presidential run in 1872 and subsequent death, the Tribune passed to the hands of newspaper editor and politician Whitelaw Reid. Reid continued to grow the publication following the Civil War and began printing the newspaper on the linotype machine, invented by German-American Ottmar Mergenthaler. This invention allowed daily issues to expand beyond its standard of eight pages. Reid’s son, Ogden Mills Reid, eventually assumed ownership of the Tribune and purchased the New York Herald to form a new publication called the New York Herald Tribune which remained in publication until 1966. However, the newspaper's influence remained paramount during the Civil War, as Greeley's journalism kept the American populous informed about the conflict and helped to shape national public opinion.