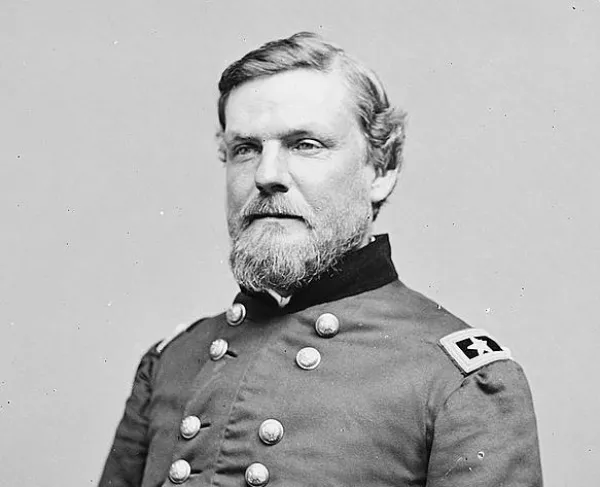

Benjamin Wade

Benjamin Franklin “Bluff” Wade was born on October 27, 1800, in Feeding Hills, Massachusetts. He grew up working as a laborer. His family moved to Ohio in 1821, and two years later, Wade moved to New York to study medicine. However, after deciding not to pursue medicine, Wade returned to Ohio and began studying law. He opened a law office a few years later in Jefferson, Ohio. Wade eased into politics, first serving as a prosecuting attorney, and then as a local judge, before being elected to the Ohio Senate, serving terms from 1837-1838 and 1841-1842.

Wade was known to be outspoken and uncompromising in his convictions. He was an abolitionist and a strong supporter of equal rights for Blacks. While serving in the Ohio Senate, he sought to repeal the Black Codes that were in place. Wade originally identified as a Whig, however, when the Whig party collapsed, he was instrumental in forming the new Republican Party. His unwavering opinions, combined with his support for women’s suffrage and trade unions, amongst other controversial stances, established his reputation as a Radical Republican.

In 1851, Wade was elected to the United States Senate and served as a Senator until 1858. There, he befriended like minded anti-slavery activists including Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, also both Radical Republicans. Wade carried his strong opinions into the Senate, vehemently opposing both the Fugitive Slave Act and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. His strong opinions earned him a reputation as a tough opponent to the Southern senators.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Wade was appointed as chairman of the Committee on Territories, which played a major role in abolishing slavery in federal territories. From 1861 to 1862, Wade also served as the chairman of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of War. Throughout the Civil War, Wade was highly critical of Abraham Lincoln, his leadership, and the choices he made. Wade doubted the sincerity and strength of Lincoln’s anti-slavery stance, and claimed that Lincoln’s views on slavery “could only come of one born of poor white trash and educated in a slave state.” Wade also spoke negatively about Lincoln’s delay in appointing Black soldiers to the army. When Wade became aware of Lincoln’s plans for reconstruction, he criticized them and said that the Confederacy needed to be handled through military means, rather than through negotiation.

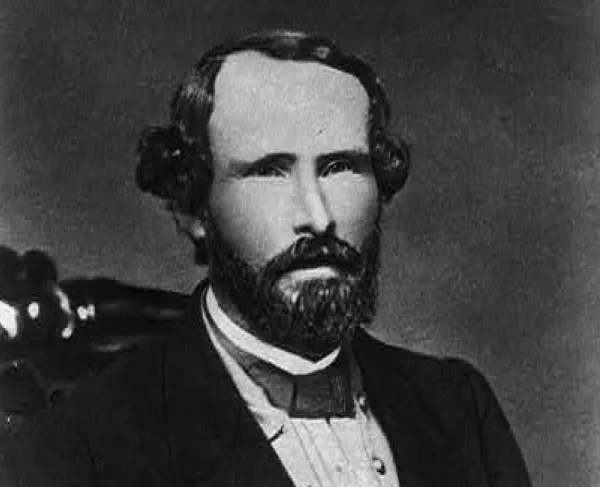

His opposition to Lincoln’s reconstruction plans prompted the creation of his own plan for post-war reconstruction. He penned the Wade-Davis Bill alongside Representative Henry Winter Davis, a fellow Radical Republican. The Wade-Davis Bill called for stricter regulations on the South after the war. The Bill also demanded that more conditions be met by the Southern states, including giving Black men the right to vote, before their readmission into the Union. The Wade-Davis Bill passed through Congress, however, President Lincoln refused to sign it, meaning it was never made into law. In August 1864, Wade and Henry Winter Davis issued a manifesto, which they called "To the Supporters of the Government," in which they accused Lincoln of trying to usurp power from Congress.

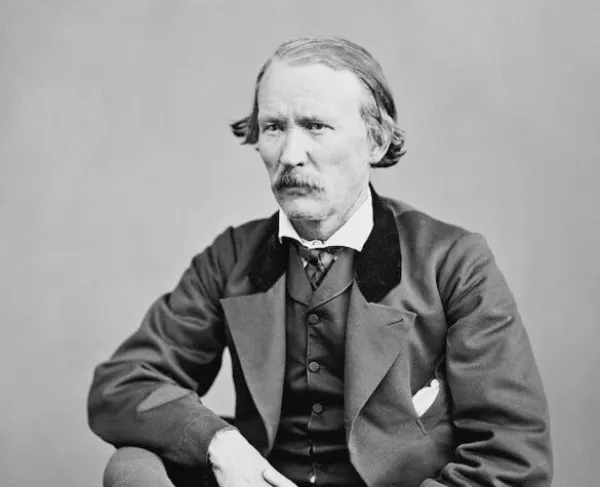

After the Civil War ended, Wade continued to advocate for the rights of Blacks, and called for the civil rights of freedmen. He supported numerous civil rights bills, as well as the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to Blacks. Wade proposed that during the post-war peacetime period, the military should include two cavalry regiments made up of Black soldiers. This proposed legislation was passed, and the first Black contingent in the regular United States Army was created.

Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, became another target of Wade’s disapproval. Wade believed that President Johnson’s plans to reunite the country after the war were too lenient. Under Johnson, Wade was elected leader of the Senate in 1867, a position known as President pro tempore. Because President Johnson lacked a vice president, if he were impeached, Wade would become President. Johnson was disliked by many in Congress, especially members of the Republican party, and fell under scrutiny for numerous reasons, including his plans for Reconstruction. In 1868, Johnson was impeached by the House of Representatives. However, three months later, he was acquitted by the Senate. Some have claimed that although Johnson was guilty, his impeachment was not seen through simply because the Senate did not want the radical Wade to take over as President. John Roy Lynch, a Black congressman elected during Reconstruction, claimed that “some of [Wade’s] senatorial Republican associates should feel that the best service they could render their country would be to do all in their power to prevent such a man from being elevated to the Presidency.” Lynch emphasized that while Wade was highly capable, he was likely to make many enemies in office and have greater success in creating jealous and fearful rivals, rather than allies.

Wade’s political career began to wane after this failure to secure the Presidency. Within the same year, Wade was not reelected to the Senate. Furthermore, despite being favored for the position, he was also not chosen as Vice President under the newly elected President, Ulysses S. Grant. Following this string of political shortcomings, Benjamin Wade returned to Ohio to reopen his law office. From Ohio, Wade kept certain political ties while working as a lawyer. He became the government director of the Union Pacific Railroad and served on a commission contemplating the purchase of the Dominican Republic. In 1876, Wade served as an elector for incoming President Rutherford B. Hayes. Benjamin Wade died on March 2, 1878, in Jefferson, Ohio. He is remembered for his strength in convictions, his honesty, and his fearlessness.